Whether all authorities agree with what is averred here—that Ernest Hemingway was one of America’s greatest writers—is uncertain. Surely, however, his work constituted a watershed; if his chastened style and objective manner no longer seem striking, it is because subsequent American writing owes so much to him that his originality is disguised. Prima facie evidence of his enduring appeal is offered by the amazingly vigorous Hemingway industry, which rejuvenates itself according to critical trends, now ranging—as a current publisher’s catalogue notes—from “formalist and structuralist theory to cultural and interdisciplinary explorations.” Holdings of a library with which I am familiar indicate that, since 1990, at least 136 volumes have appeared that are devoted, in whole or considerable part, to his life and writings.

Valerie Hemingway, née Danby-Smith, author of the present memoir, married Ernest’s youngest son, Gregory, in 1966. She had served for approximately a year as secretary and factotum to Ernest after their initial meeting, in 1959, in Spain. After his suicide in July 1961, she became a sort of aide-de-camp to Mary, his fourth wife and widow, helping her close the house in Cuba and, despite the embargo on outgoing shipments, remove the writer’s very valuable property—manuscripts, correspondence, books, paintings. Valerie then assisted Mary in countless other ways, including sorting of papers, in an office provided by Scribner’s. (Later, she worked as a journalist and publishers’ publicity agent.)

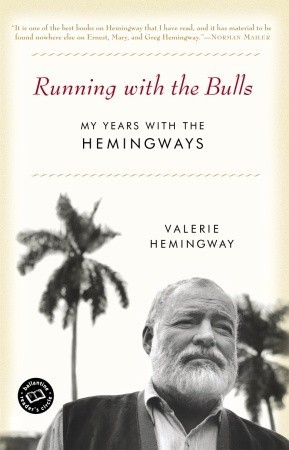

The subtitle of this book, featuring Hemingway in the plural, is thus justified, whereas the main title (chosen perhaps to attract attention and stress anew the writer’s machismo) is misleading, since most of the book does not concern Miss Danby-Smith’s and Ernest’s time in Spain. The memoir bears encomiastic endorsements from well-known figures: Norman Mailer, Tom Brokaw, and biographer Jeffrey Meyers. After beginning with Hemingway’s funeral, the narrative returns to the memoirist’s birth (in 1940 in Dublin, of Anglo-Irish parents), her convent upbringing, and her early career as a journalist; it then recounts her time in the great man’s company and traces in detail her subsequent activities. Many passages concern his family and friends, shoved into prominence in literary history by virtue of being in his circle. The memoir thus complements writings by other Hemingways, including Leicester (Ernest’s brother), Gregory, Mary, and Hemingway’s son Jack, as well as standard biographies by Carlos Baker, Meyers, and others. While many pages overlap with their accounts, the author furnishes, presumably, certain details known chiefly to her.

The memoir is something of a buffet, where one may select what one likes. If you want further evidence of Ernest’s need to dominate others, you can get it here. If you appreciate him as an aficionado of tauromachy, you will be served. If Mailer interests you, you will note his portrait. Should you be interested in Brendan Behan, you will observe what Valerie has to say about her affair with him, which led to the birth of an illegitimate child. If you wish to learn even more about Hemingway’s relationships with women, you can study Valerie’s reactions, at age 19, to him and follow his growing fascination with her; the relationship has been traced before, but not so personally. He intended, she writes, to marry her, since Mary no longer cared about him. Valerie’s role in keeping certain papers from the public, including letters between her and Ernest (one escaped, by chance) and between Ernest and Gregory, is noteworthy. (While Mary set policy, Valerie, charged with the triage of materials, made many decisions.)

The most striking character, after Ernest, is Gregory. To be Ernest Hemingway’s son was apparently a dreadful fate, and to be married to the son was almost as bad. Valerie’s tale is cautionary, demonstrating amply that the artistic life, when it approaches Rimbaud’s “long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens,” is disordered, unhealthy, unproductive, and unhappy, if not dangerous and downright immoral, and that these ills are often visited on artists’ families also. Who and what were responsible for Gregory’s character and behavior cannot, of course, be determined with certainty. At age 19, he had a bitter quarrel with his father, which led to permanent estrangement. He was plainly self-destructive. After Valerie and he wed—he had been married twice before—evidence of a profoundly disturbed personality, which she calls manic-depressive, became abundant. Though he fathered children, he was a compulsive cross-dresser; he confessed that he had worn items of women’s clothing even as a boy. He drank excessively and took illegal drugs. Trained as a physician, he did not finish any of the specialized medicine courses for which he registered; he rarely held a position for long, uprooted his family frequently, lived recklessly and spent money foolishly, and was, in short, unreliable and ineffectual. For months on end, he did not work at all. Her Anglo-Irish upbringing notwithstanding, Valerie had been converted to belief in the efficacy of psychiatry, whether employing verbal or pharmaceutical means. As she puts it, in New York, where they lived for some years, going to therapy was “a matter of pride, a status symbol.” She thus placed considerable hope in “cures” of one sort or another, as did Gregory, ostensibly, at least; he submitted to electric-shock treatments, took strong antidepressants, and sought out counseling, all in vain. Yet psychiatrists repeatedly stated, orally and on paper, that he was rational and stable. One, after making an official declaration to that effect, told Valerie that, even if the contrary were true, he would never “rat on” a fellow doctor and, thus, would have concealed any unfavorable diagnosis. In short, the psychiatrists’ record in his case, as in that of Ernest, who was misdiagnosed, is deplorable.

In Montana, during the last years of their marriage, Gregory grew wilder: threatening, drugging, and hitting his wife, jeopardizing the children’s safety, parading as a transvestite, and often causing such commotion that he was arrested. He proposed undergoing a “sex change” and, ultimately, in 1995—by then, Valerie had left him—carried out that plan. When he telephoned from a distant motel to say that, having left the clinic before the recuperation period ended, he was hemorrhaging badly, a son was dispatched to assist him. Confined in an asylum, he was allowed to leave in order to fly to Atlanta, where he was to check himself into an institution for addicted physicians. Instead, at the Atlanta airport, he simply took another plane to Miami. He died five years later in a New York women’s prison of heart disease, apparently, after having been picked up in the street five days before, naked but carrying a dress and high-heeled shoes.

Whatever one thinks of Ernest Hem-ing-way, one is unlikely to blame him wholly for such deviancy, next to which his own life appears nearly normal, at least during the decades when, as Meyers wrote, his life was marked by “personal and aesthetic emphasis on truth and reality.” The parents’ neglect of the boy when he was small cannot have been good, however, nor pressures on him to perform well (often he did, but that only increased the burden) and, as Valerie suggests, incipient rivalry with such an attractive but overbearing father. Worst of all may have been the example of self-indulgence set by the writer, who lived hedonistically even as he practiced literary discipline. Valerie and Gregory’s tale is instructive, if banal; only the fact that, ultimately, Hemingway is at its center prevents it from being just another sordid story of failure, flight from responsibility, and wounding of those one loves—the sort spilled out in barrooms and on psychiatrists’ couches every week.

Valerie Hemingway’s style, though ordinary and marred occasionally by clichés and repetitions, is serviceable. The numerous errors in grammar and usage, however, are deplorable—among others, comma splices; their as a singular possessive; brought for taken; dangling or misplaced participles; me for I; and frequent misuse of the reflexive myself. This is supposed to be a literary memoir. What has happened to editing? Editors, where they exist, must have been recruited from the sort of students who resisted my attempts to enlighten them (in French class) on matters of English grammar. It would be unreasonable to expect Hemingway critics and biographers to emulate the high performance standards of the bullfighters he admired, such as Ordóñez, for whom errors meant dishonor—if not loss of life—or even his own exacting writing requirements; but care in language would be a way of paying him homage.

[Running With the Bulls: My Years With the Hemingways, by Valerie Hemingway (New York: Ballantine Books) 313 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply