“A joke is an epitaph on an emotion.”

—Nietzsche

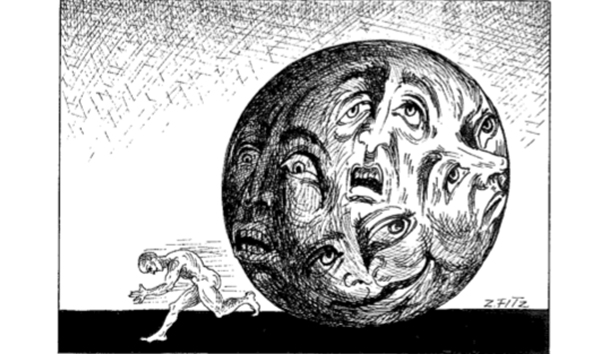

Telling truth in the form of a lie is one of the odder things human beings do. It is hard to imagine irony in Paradise, and there can certainly be none in Heaven, where we know even as we are known, and there is nothing to hide and nothing hideable. In Paradise after the Fall, on the other hand, God’s first words—”Where art thou?”—would sound ironic to guilty Adam, who may not have known the word, but who had done the thing: the root meaning of irony is “dissimulation.”

We begin to speak ironically very early in life, although most of us first become conscious of irony in adolescence, when we learn simultaneously that it is admired in writing and disapproved of by our parents and teachers. Later on, probably at the university, we learn that irony can be an attitude of mind, a kind of universal solvent capable, as Keats said in another connection, of making all disagreeables evaporate. Later still, when we know more and are certain of less, the ironic attitude will seem less a sanctuary and much more a funkhole.

To simplify a complex problem, irony draws bus power to amuse, infuriate, protect, and proclaim from the circumstance that things are seldom what they seem. There appear to be two chief kinds of irony: one that announces a fact, another that evades it. Whether you enjoy the irony will depend on your assessment of the fact unless—like the American electorate—you dislike irony on principle. Certainly, irony raises difficulties, and books about it ought to be interesting, if only for the examples.

On the whole they are not. Like other figures of speech, irony is more interesting to read than to read about. Besides, ironists have a reputation as clever, sophisticated, even profound people, and no writer on the subject wants to seem less clever than his subjects. This often leads to unnecessary convolution and indirection. The worst temptation is to treat irony ironically. Kierkegaard did this, and it is to D.J. Enright’s credit that he says early on in this book that he found Kierkegaard’s essay incomprehensible.

That kind of willingness to speak plainly is Enright’s strength. Irony, though, is not a mode one associates with him. A writer who publishes the lines “And wash the coated tongue that it might speak” or “Who was it slid the noiseless shoji?” (from Bread Rather Than Blossoms) hasn’t the self-protectiveness of the ironist, or his capacity for seeing that everything, including a reader’s response, has at least two sides. Perhaps irony allures Enright because in some ways it evades him. Many of his ironies depend on attitudes not everyone will share, and many of the grand examples that our whole culture has recognized are missing.

His book is not, as the title says, an essay so much as 28 little essays, a personal album of ironies with comment and explanation. The intention is to be lively, unacademic, apothegmatic, to appeal to a taste for one thing itself and intelligent talk about it.

Up to a point, Enright succeeds. The comment is succinct, often interesting and fair. The author knows how to present himself as a character in his own right, and the personal vignettes—Enright in Singapore, Enright dodging a large policeman—are enjoyable. Why, then, does the book seem bland and accommodating, so unprovoked by a provoking subject? The answer is in the conclusion: “Irony lives in the ample territory between [paradise and hell]; it acknowledges what must be, contends against what should not and need not be, and intimates what conceivably could be.” In other words, irony is a social democrat. She has a clear conscience and does good, socially responsible things: she acknowledges, contends, and intimates. Who could object to that? She also knows what’s what, and has the good taste not to define it.

So despite the book’s form, Enright’s irony is academic, center-left, timid, and conventional. The examples often reflect the academic curriculum of the 50’s and 60’s—Donne, Marveil, Austen, Fielding—all well worked over, the comment well within the expected, aimed straight at an academic audience. Only a very thinskinned academic will object to the carefully oblique censure of the revolting Brecht. Like Enright, most academics will share Wayne Booth’s surprise that a student’s paper on deerhunting could be sincere, and sympathize with Dan Jacobson’s shock on realizing that a line-’em-up-and-shoot’em Englishman’s talk was not a put-on. Yet, can such surprises be genuine? Whatever one thinks of bloodsporters and gunboat diplomats, surely it is odd that the ironic attitude of raised eyebrow and gathered skirt (imputed irony, one might call it), once the protection of gentility against foul-smelling mobs, should survive in academic common rooms.

Hence a well-intentioned essay proves to be a Hamlet without the prince. Irony is not academic at all. In Anglo-American tradition, whose literature is overwhelmingly Christian, the facts underlying the greater ironies derive from revelation—from such things as the news that wisdom is folly, that the first shall be last, and that he who gains the world will lose his soul. In that tradition there is nothing frivolous or evasive in saying that things are not what they seem. This gives the ironies of the masters their power, whether comic or tragic: Chaucer, More, Erasmus, Shakespeare, and Swift among the classics, Chesterton, Waugh, Powell, Spark, and Amis among the moderns. None of them, except Shakespeare and Swift, figures in this book.

“There is apparently less irony to be extracted from Shakespeare,” says Enright, “than one might expect of our national poet.” If you think of Shakespeare as a national poet, and look for verbal ironies, that may be true. Approach him as a Christian poet, and the case is much altered. As Kenneth Muir said years ago, the center of King Lear, the storm-scene of Act 3, turns on a verse from the Magnificat: He hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted the humble and meek. Enright’s comment on Lear is trivial compared to this. His treatment of Swift, though, focuses the point.

For a long time, Swift’s A Modest Proposal (which, as Chronicles readers will remember, was that the state of Ireland was so bad, its only recourse was to sell the children for food) has been used as a crash-course in irony for unsuspecting freshmen and, more recently, high-school students: an inept solution, whether you consider the future of literature or of the students. Some students always take Swift straight, and suffer bewilderment, while some of their teachers make merry over the fact, and others express concern. Yet, it might be that these students are victims of an unpleasant practical joke, of a kind that would certainly disgust Jonathan Swift. Well: it seems that a school board somewhere in New York state banned the pamphlet on grounds of bad taste, something that Enright finds “beyond the bounds of credibility.” And up go those eyebrows again.

Swift would agree that A Modest Proposal is in bad taste, but then so was the state of Ireland. As an orthodox Church of Ireland priest. Swift must have assumed that his readers would recognize the scriptural ground bass of his irony. Any mention of murdering children should make a Christian think first of the Slaughter of the Innocents, always explained to him as absolute evil, and aimed at the life of his own Savior, who came as a little child; then of the Savior’s words:

Whoso shall offend one of these

little ones which

believe in me, it were better for

him that a millstone

were hanged about his neck,

and that he were drowned

in the depths of the sea.

No Christian reader can mistake Swift’s purpose. Non-Christian readers in secular schools, on the other hand, might miss the point entirely, might even think there’s something to be said for the idea; the best they’ll be able to do is discuss something called “the irony” in a mirthless, self-satisfied way. Anyone might call that bad taste. Worse still from the standpoint of a school board, readers with Christian inklings might connect Swift’s variation on the Slaughter of the Innocents with their own America as well as with 18th-century Ireland. In schools where abortion is not unheard-of. Swift’s bitter indignation might sear some consciences. And that would be in even worse taste.

Neither I nor D.J. Enright knows what lay behind the school board’s decision to keep Swift out of their classrooms. It would be equally interesting to know why Enright would include him. No sensible person wants to see Swift banned; no sensible person wants to see him intruded upon youngsters not ready for him, either, or made the subject of academic trivialities. And how curious that Enright should be so scornful of these New Yorkers when he has left so many of the greatest ironists out of his own collection! This is a more serious lacuna in a book on irony than the omission of Swift—for whatever reason—from an 18-year-old’s reading list. Where is Chaucer’s trendy monk who wanted to know how the world should be served, Erasmus’ Folly who said that Christianity could be very hard on the clergy? One suspects that they and their modern descendants, also missing, belong to another world and another book.

[The Alluring Problem: An Essay in Irony, by D.J. Enright; New York: Oxford University Press]

Leave a Reply