“In fourteen-hundred and ninety-two,

Columbus sailed the ocean nude.”

—Chronicles, 1992

The profusion of the anti-Western virus released by the quincentenary of Columbus’ landfall on the Caribbean island of San Salvador has become the mental equivalent of the AIDS epidemic, fatally infecting millions of promiscuous and incautious intellectuals and subintellectuals. For the literary ghetto, Kirkpatrick Sale is the sinister Mr. X to whose book The Conquest of Paradise, published in the fall of 1990, many subsequent cases of this formerly incurable disease can be traced. Today the reading public can be thankful that an effective antidote has at last been discovered and developed by Robert Royal, vice president and researcher at The Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C.

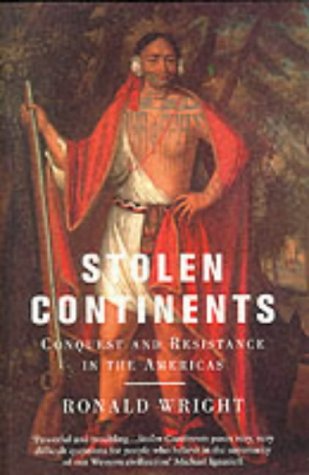

Ronald Wright’s talents as an historian, observer, and writer make his affliction the more tragic: the extreme tendentiousness of Stolen Continents does not lessen the readability of his book, though it does vitiate it. Mr. Wright is the personification of the left’s inability to think historically. His account of how five indigenous peoples—the Aztec, Maya, Inca, Cherokee, and Iroquois—suffered invasion by the white Europeans, offered them resistance, and finally induced a “rebirth” of their uprooted and smothered cultures is so outrageously one-sided and given to special pleading that the final effect is to undercut the reader’s confidence in the author’s trustworthiness. In 346 pages of text, literally no overt criticism of Native American culture, belief, or deeds is offered, while the entire rhetorical structure is designed to point up the evil of European civilization and the cruelty, mean spiritedness, and hypocrisy of its agents and representatives. Wright, a native of England now resident in Canada, tells how as a student he was bored by the histories of ancient Greece and Rome and of the Tudors and Stuarts, concluded that there must be something else, and found it in the history of the Inca. In Ronald Wright’s case as in most others, boredom is a result of a lack of empathy. For Wright, it is not enough that modern Mexico is what Royal calls “a melding of cultures,” native, mestizo, and European: anything short of the preservation of Aztec society in its pre-Columbian form, intact and unadulterated, represents an historical crime—the result of dragging the Aztec, kicking and screaming, into History, another evil European invention. Andrew Lytic in his novel At the Moon’s Inn, by treating De Soto’s invasion of Florida as a prefiguration of the rape of the Old South by Union generals, in a sense anticipated the inversion of cultural values that is being practiced fifty years later with infinitely less nuance and wisdom. Would Ronald Wright, who belongs to the species of leftist that champions “tradition” while scorning “progress,” be willing to defend the “traditionalist” values of the Confederacy against the onslaught by the “progressive” Unionists? Somehow I doubt that the multiculturalist fervor extends so far as that.

Stolen Continents, like all of the recent anti-Columbian literature, is fundamentally dishonest work; an intellectual set-up disingenuously assuming a historical consensus that the Indians were never more than Stone Age savages incapable of anything properly describable as civilization. This sleight-of-hand makes it possible for the revisionist historian to strike a blow for enlightenment by gushing over Long Houses built of logs and bark and “town houses” supported by poles inset in rock, as though the germane comparison were with mud huts and igloos rather than with St. Paul’s Cathedral. In fact, Europeans in the colonial Americas were frequently impressed by what they saw of Indian culture and said so, as Wright’s own documentation shows. Other examples of fast-and-loose techniques are Wright’s equation of the rough adventurers who were the cutting edge of European exploration and colonization with European society as a whole (the da Vincis, Saint Theresas, and Pascals of any civilization are not generally found in such vigorous vanguards) and his adverse comparison of these with the generality of the Indian civilizations they conquered; his tendency to judge the Indians according to their ideals and beliefs, while condemning the Europeans for their individual actions (European ideals are understood to be simple hypocrisy); a nearly infinite capacity for appreciating the most bizarre absurdities of Indian religion while taking snide pokes at the Europeans’ “absolutist” theology of “the three gods” and the “creed that regards the quintessential creature of the earth as evil” (Wright can’t have been paying any more attention in Bible class than he was to lectures on Tudor and Stuart history); and an implicit insistence that the actions of nations and individuals can and ought to be judged by identical moral strictures. (Reinhold Niebuhr explained more than a generation ago why this is not the case, but the left as usual wasn’t listening.) Finally, there is simply too much evidence of native barbarism, savagery, cruelty, and ignorance eliminated from the narrative, too much soft-pedaling of what few examples of red mischief are unavoidably included.

The undeclared enemy of the anti-Columbian syllabus is Christianity even more than it is capitalism, imperialism, ethnocentricity, and genocide, which the revisionists assume to be derivative from the Gospels in any case. (A “serious” work of history forthcoming from a major New York publisher this fall answers the question “What kind of people could have behaved as the Europeans did in the Americas?” with the single word “Christians.”) In 1492 And All That Robert Royal, a Roman Catholic apologist for time and Western man, provides the best imaginable rebuttal to the Zeitgeist. In a book of 200 pages (Kirkpatrick Sale’s screed runs to 453), he has simply demolished a burgeoning body of fake scholarship—including especially that of Kirkpatrick Sale.

Mr. Royal strikes with vigor and lands blows on every front. He begins with Christopher Columbus himself and shows how unrealistic in both a historical and a personal sense the revisionist’s critique of El Almirante is, arguing that the new Columbus “is merely the product of various opposite evil traditions that define Europe and Europeans—of which we are all the heirs, save, of course, the Kirkpatrick Sales who transcend cultural determinism.”

In subsequent chapters. Royal demonstrates how contact with the primitive peoples of their expanding empire encouraged the Spaniards to debate “in remarkably open fashion” the moral issues raised by conquest overseas. In 1500 Queen Isabella outlawed the practice of selling Native Americans from the docks of Spanish ports, and in 1550 Charles V ordered a theological commission to be convened in Valladolid for the purpose of establishing a more scrupulous moral basis for the governance of the Indians. The Dominican Order developed itself as a kind of unofficial Catholic Society for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Dominican friar and theologian Francisco de Vitoria formulated a system of principles recognizing and protecting the rights of the aborigines as rational beings and children of Cod; his two collections of lectures on the subject, De Indis and De Iuri Belli, earn him a place with Suarez and Crotius as one of the fathers of modern international law. In his dissection of the contemporary fetish of “multiculturalism,” Royal observes that the Europeans were for the most part much more receptive to the new and the exotic than the Indians themselves were, and that they were in a far better position to “understand” these primitives than to be understood by them. (“Most Indian groups regarded only themselves as full human beings and members of other tribes as inferior in customs or understanding.”) The notion of pluralism, he reminds us, is itself a distinctively European idea: “The wish to contest an allegedly monolithic European view of history with fresh voices and perspectives inescapably belongs to a very European mode of thought.” (“The cultural pluralism that we value so highly did not exist within any tribe.”) While acknowledging that the idea that Columbus “discovered” America is anathema to anti-Columbian activists. Royal suggests “it would be unfair to ignore the fact that [Columbus] did something more far-reaching. He may not have proved the world was round for Europeans, but he did so for Native Americans. And in so doing, he inaugurated the age in which, finally, all the world’s people inhabited one world and knew they inhabited it, though that realization was slow to be accepted in many newly discovered lands.” Almost in passing, Royal takes out the positions of assorted stragglers in the train of the anti-Columbian troops by a series of bazooka attacks disproving the notion that the Indians were feminists, egalitarians, communitarians, and environmentalists. (After graphically describing the Aztec equivalent of open-heart surgery he remarks, “This too is harmony with nature, but a harmony that depends, as all such philosophical concepts do, on your beliefs about nature and the gods.”) Finally Royal, having criticized the double standard on which the whole anti-Columbiad is based, identifies the crusade “in its most profound moments” as “a Western objection to the disappearance or attenuation of human riches within the West itself,” and concludes: “Like it or not. Western culture with its own particularities and its openness to light from the outside is the cultural matrix upon which the world has become, if not unified, then set on a path of something like universal mutual intercourse. No other culture in the world has—or probably could have—undertaken that task.”

1492 And All That is a masterful book, brilliantly argued and eloquently written; one of the very few titles to which the cliched publisher’s claims of “Absolutely required reading,” or “A truly indispensable work” could fairly be applied. The real question to emerge from the Columbus controversy is, of course, “Could history have been otherwise?” Robert Royal is a wise—perhaps even a brave—enough man to assure us: it couldn’t. Perhaps, even, shouldn’t. “The glory of Rome and the splendor of India, as their own high cultures recognized, were rooted—as are all largescale human endeavors—in human loss, contradictions, and moral doubt, for which Vergil invented the immortal phrase lacrimae rerum. . . . Tragedy is probably sharpest when the situation dictates that a choice be made between incompatible goods leading to the unavoidable loss of something humanly valuable. Even in epic achievements human costs inevitably must be paid. Epic and tragedy do not conceal truth beneath artificiality but open windows onto a fuller reality.”

The native societies of the Western Hemisphere were finally overcome by History, which the left has always refused to recognize or tolerate in its quest for a secular and ahistorical paradise on earth. They were neither its first victims nor will they be its last, as in the end we all may be. If Fate exists, surely it is because History indeed does have a plan.

[Stolen Continents: The Americas Through Indian Eyes Since 1492, by Ronald Wright (Boston: Houghton Mifflin) 424 pp., $22.95]

[1492 And All That: Political Manipulations of History, by Robert Royal (Washington, D.C.; The Ethics and Public Policy Center) 200 pp., $18.95]

Leave a Reply