Americans like to think this is a land of diversity unparalleled anywhere in the world, but in religious matters at least, such a view is far from the truth. America remains today substantially what it has always been, namely, a Christian country. While the United States is indeed home to a remarkable number of religious denominations, overwhelmingly, these are currents within the broader stream of Christianity. Adherents of non-Christian religions are strikingly few. If we combine the best plausible estimates for the numbers of American Jews, Buddhists, Muslims, and Hindus, then we are speaking at most of four percent of the total population. Even if we exclude Mormons from the Christian community, this only raises the non-Christian total to around six percent. The degree of religious diversity in the United States is very limited compared to what we find in many African and Asian countries, where religious minorities commonly make up 20 percent of the people, if not more. Contrary to American perceptions, some of the most diverse lands are found in the Middle East, which Westerners often imagine in terms of Muslim homogeneity and intolerance: Countries such as Egypt and Iraq are far more diverse than the United States. American religious homogeneity is actually likely to increase in the coming decades, as our population becomes more diverse ethnically. A large proportion of the latest wave of Asian, Latino, and even Arab immigration is Christian, often fervently so, while the non-Christians seem ripe for evangelistic efforts, particularly by conservative and Pentecostal denominations.

The existence of a powerful American Christianity is open to many interpretations: Some believe that a Christian people requires a Christian government, with all that implies about religious exercises in schools, while extremists advocate a theocratic state. On the other hand, many argue that the sheer numerical weight of Christianity requires the counterbalance of a rigid secular state. Hence the ongoing and often trivial seeming controversies about public displays of religion—creche scenes on courthouse lawns, commencement prayers, and the like.

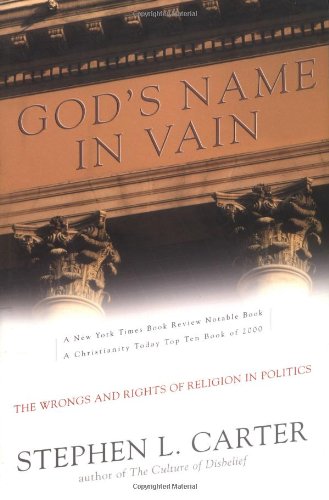

Stephen L. Carter is a Yale law professor whose 1994 book, The Culture of Disbelief, made a provocative and balanced contribution to the debate about the role of religion in a supposedly secular state. His earlier work bore the subtitle, “How American Law and Politics Trivialize Religious Devotion,” and offered many telling examples of the selective response by the media and the political elite to public expressions of faith. In secular eyes, it was completely acceptable for Martin Luther King to engage in his crusade, and even to be identified publicly as “the Reverend,” but utterly taboo when conservative politicians (or even clergy) invoke Cod in their particular causes. The more the secular elites seek to exclude religion from the public sphere, the further removed America’s rulers become from their subjects, and the more the media depict the worldview of the ordinary person as a form of incomprehensible fanaticism. I offer this modest proposal to some aspiring filmmaker in search of a topic: Make a documentary that strings together the typical depictions of religious believers or pastors in mainstream American movies of the last 20 years or so. The clips could be united by titles such as “homicidal maniac,” “babbling fanatic,” “hate-spouting hypocrite,” “child molester,” “self-hating homosexual”—the list is endless.

Religious issues remain at the forefront of American politics. The proper place of religion was discussed in the context of the religious forms affected by President Clinton’s “confession” of sin in the Monica Lewinsky affair, and the response by the liberal media. Over the last few months, both presidential (and vice-presidential) candidates have tried to out-God each other. Increasingly, Americans seem to favor a greater public role for religious voices; see the surveys in an important recent book from the Brookings Institute, The Diminishing Divide. A new salvo by Carter was therefore to be expected, and his work thoroughly meets our expectations. God’s Name in Vain is a sane, intelligent, and lucid analysis, which can profitably be read by activists of all shades, as well as by anyone interested in American politics.

Carter offers a new assessment of the state of the debate. His judicious views are summarized in two primary theses: “First, that there is nothing wrong, and much right, with the robust participation of the nation’s many religious voices in debates over matters of public moment. Second, that religions —although not democracy—will almost certainly lose their best, most spiritual selves when they choose to be involved in the partisan, electoral side of our politics.” These two views may initially seem contradictory— amounting, crudely, to the proposition that while the churches have a right to speak out, they really shouldn’t—but Carter’s case is far more subtle than this reductive summary might suggest. He stresses the critical role played by religion, often of the most fundamentalist and evangelical stripe, in political debates throughout American history, not least in the civil-rights movement. And just how, exactly, should 19th-century religious activists have refrained from crossing the wall of separation between church and state on issues such as slavery? To understand American history, we must never underestimate the sincerity or determination of those in every generation who have sought to construct “the kingdom of Cod on earth,” however they conceived this goal. As Carter argues, “Religion, in short, has no sphere . . . . The law today too often behaves as though it does.” Carter goes so far as to proclaim that, in a hypothetical conflict between God and country, he would be required to relinquish the cause of his country: As much as he loves the United States, it is no more eternal or indispensable than the Roman Empire of its day.

Yet God’s Name in Vain is no call for a religio-political crusade, still less for a specifically religious agenda in politics. Carter warns religious activists that, “When you touch politics, it touches you back. Politics is a dirty business at best, and leaves few of its participants unsullied. The religious enjoy no special immunity. On the contrary—the religious face special risks.” Not the least of these risks is that religious activists will be held to a higher standard of responsibility than secular politicians. The public will, rightly, demand the highest possible standards of behavior and will be deeply sensitive to any apparent hypocrisy or powerseeking, not to mention more obvious failings in financial and sexual integrity. If religious leaders fail to meet these standards, the results will be disastrous not just for the causes they have adopted, hut for the denominations and creeds they represent. The experiences of the Moral Majority and the Christian Coalition present many such examples.

Ultimately, Carter warns, the danger is that, as religion “gets into” politics, it becomes no more than politics—and what a fall that is. At worst, in such instances, religion really does become the worst kind of hypocrisy, even a mask for demagogues. We recall Santayana’s celebrated definition of fanaticism as redoubling your efforts when you have forgotten your original goal. Carter concludes with a plea never to forget the heart of the matter: “Without renewal, without a retreat from the wilderness and a return to the garden, without more time spent listening to the voice of God . . . without these necessities, religion will be nothing too.”

[God’s Name in Vain: The Wrongs and Rights of Religion in Politics, by Stephen L. Carter (New York: Basic Books) 264 pp., $26.00]

Leave a Reply