Few people read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) much anymore. Lines from his poems were once on the tips of tongues the world over. Students used to memorize “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere,” and lines from “Evan-geline” and “Hiawatha.” Longfellow’s once-great literary reputation rivaled that of Tennyson and Dickens, and, after his death, the American poet was singularly honored by having his bust placed in Westminster Abbey with the greatest English poets. When Longfellow is mentioned at all today, however, he is held up to ridicule by modern academics and dismissed. His gentle Christian nature would have accepted his waning reputation tranquilly. Perhaps he would even quote from one of his poems: “The tide rises and the tide falls / The twilight darkens, the curlew calls.”

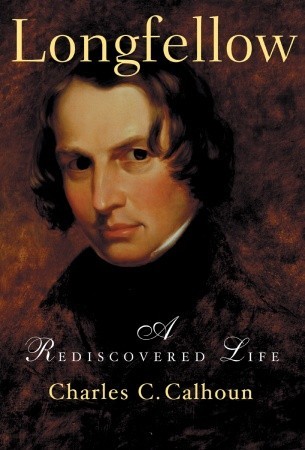

Charles Calhoun’s new biography, which is both overdue and welcome, would rescue Longfellow from the surrounding darkness. The book’s cover sports a handsome portrait of the poet at 33 years of age. Longfellow is generally pictured as an old man with flowing white beard. But he, too, had his youth and, when young, was a bit of a dandy. A clever student at Harvard’s Hasty Pudding Club wrote of the Smith Professor of French and Spanish:

Just twig the Professor dressed out in his best

Yellow kids and buff gaiters, green breeches, blue vest;

With hat on one whisker and an air that says go it

Look here the great North American poet.

A staff member on the Maine Humanities Council, Calhoun is a skilled biographer who has written a book that is a pleasure to read. His comments on Longfellow’s poetry are sensible and persuasive, righting a great wrong in American literary history.

Born in Maine on February 27, 1807 (when that state was still part of Massachusetts), Longfellow led an interesting life. His father, a prominent lawyer, sent young Henry to Bowdoin College, where he graduated along with Nathaniel Hawthorne. Longfellow then left America for three years to study language in Europe. An accomplished linguist, he once had to produce an American passport to prove that he was not a native Italian. Always, he retained a sunny Mediterranean disposition. Upon his return to the United States, he taught modern languages at Bowdoin. Six years later, he again set out for Europe, returned a widower after his first wife perished from a miscarriage in Rotterdam, and took up a professorship at Harvard. But Longfellow was eager to retire from teaching to devote himself to poetry. He married Fanny Appleton and purchased a house in Cambridge that had once served as George Washington’s headquarters. Here, the founding father of American poetry produced his great works.

Longfellow’s sonnets are among the finest in the English language. Those dedicated to Dante come from his beautiful translation of the Divine Comedy and are tinged with the sadness Longfellow felt over the frightful fate of his beloved Fanny, who burned to death in 1861. (Calhoun has uncovered new information suggesting that Fanny’s skirts caught fire after being set alight by one of the children, who was playing with matches.) Longfellow, in attempting to put out the fire, was so badly burned that he grew a beard to cover the facial scars.

Calhoun seems a bit tentative defending Longfellow. He need not be. Philip Larkin took the academic critics and their domiciled poets head on, charging that “They produce a new kind of bad poetry, not the old kind that tries to move the reader, but one that does not even try.” It came about because of a “cunning merger between the modern poet, literary critic and academic.” This modern monopoly manufactures products Longfellow would not recognize as poetry: unrhymed lines centered on a page with no sonorous sounds or resounding insights leading to the eternal.

Unlike his contemporary Ralph Waldo Emerson, Longfellow remained a faithful Christian who was strongly drawn to the Roman Catholic Church. I suspect that this is another reason he has not found favor with modern critics, who have no faith and are antithetical to things spiritual and supernatural: They inhabit a closed gnostic realm inside their own skulls. Such dry bones can harm no one. The great masters like Longfellow wrote of things eternal, and for poets yet to be born.

Longfellow believed in a communion of poets, as well as a Communion of Saints, who beckon us beyond the worldly gloom of sin and death. From an early age, he was fascinated by Dante. Longfellow’s influence led to Dante Studies being established at Harvard, and it was there that T.S. Eliot that became strongly influenced by the Florentine poet. And it was Dante who led Eliot out of the spiritual wasteland of modernity.

[Longfellow—A Rediscovered Life, by Charles H. Calhoun (New York: Beacon Press) 317 pp., $27.50]

Leave a Reply