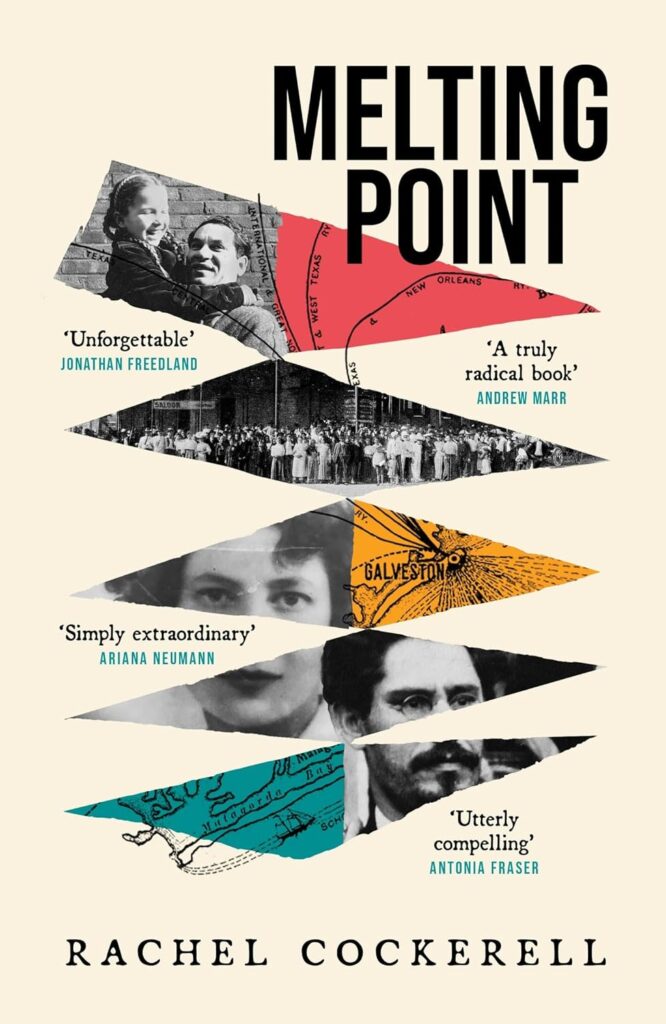

by Rachel Cockerell

Wildfire

416 pp., $32.49

Migratory disruptions are a particular challenge for the preservation of personal histories. But Melting Point, a Jewish “family history,” is not so much about preservation as it is recuperation. As recently as a few years ago, Rachel Cockerell was only vaguely aware of her Jewish ancestry on her mother’s side and completely unaware that her great-grandfather, David Jochelman, was a major figure in the Zionist movement. Her quest to discover the truth about his life has produced not just a family history but a history of the broader search for a Jewish homeland.

Cockerell employs an innovative style that has something in common with montage. In the course of writing what was, initially, a conventional narrative, she became dissatisfied with her own “twenty-first-century-tinged” observations and “useless” description of her characters’ feelings:

I gradually began to delete more and more of my own ‘voiceover’ [and] realized it might be possible to tell the whole story through the eyes of those who were there, and create something that felt more like a novel than a history.

The story she eventually produced has the vivid immediacy of a novel, but its narrator’s voice has been entirely replaced by the voices of her “characters” (taken from newspapers, histories, memoirs, interviews, letters) and spliced into the chapters without connective tissue; yet these quotations are so deftly arranged that the storyline unfolds smoothly and, for the most part, without confusion.

The book’s first half is concerned with the origins of the Zionist movement and its offspring, the Jewish Territorial Organization. Here, Theodor Herzl and Israel Zangwill take center stage. A child of the Hungarian Jewish bourgeoisie, Herzl’s vision of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine was both secular and mystical in conception. In 1895, after establishing himself as a journalist in Vienna, he wrote in his diary, “For some time past I have been occupied with a work of almost infinite grandeur … which has possessed me beyond the limits of consciousness.” That work was published as Der Judenstaat (“The Jewish State”), which called explicitly for a return of European Jewry to the Holy Land and the establishment of a modern nation-state there. In large part, his vision was driven by the waves of late 19th-century pogroms that had swept across the Russian Pale and the rise of anti-Semitic fervor in Vienna itself. Millions of diasporic Jews in Europe and elsewhere, he believed, faced the possibility of gradual extinction.

Herzl was a well-known fixture in Vienna’s elite social world, but Der Judenstaat did not find significant acceptance among his peers. As the young Stephan Zweig noted, the Viennese Jews were perplexed and irritated that this “graceful, aristocratic causeur had … written an abstruse treatise that demanded nothing less than that the Jews should leave their Ringstrasse homes … and emigrate, bag and baggage, to Palestine.” Much like the Jews in other western European enclaves, they were long since assimilated:

‘Why should we go to Palestine,’ they asked. ‘Our language is German and not Hebrew, and Austria is our homeland.’

In retrospect, such complacency seems astonishing, but in the 1890s Herzl’s critics scolded him for being much too gloomy. One writer in The Jewish Chronicle stated, “We hardly anticipate a great future for a scheme which is the outcome of despair.” Moreover, as Paul Gottfried noted some years ago in The American Conservative (“Jews Against Israel,” July 2012), many Western European Jews, especially in Germany, adhered to a Reformed Judaism that tended to see the ethnic particularity of traditional Judaism as politically and culturally retrograde. From their perspective, a Jewish state in Palestine, no matter how secular, would set the Jews apart culturally and ethnically—an affront to the universalist commitments of the Reformed tradition.

Yet the Zionist movement thrived in Eastern Europe among the Jews who had borne the brunt of the pogroms, and who were less assimilated to the Western bourgeois culture. Thus, they were more likely to respond to Herzl’s appeal to nationalist themes in the Old Testament and the Rabbinic literature, and were the most enthusiastic contingent at the first Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897.

In 1902, Herzl began to seek support from the British government. After meeting with Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, he received some encouragement that a territory for Jewish settlement might be carved out of the Sinai Peninsula, but by early 1903 that possibility evaporated. Instead, Chamberlain offered a substantial territory in East Africa, in what is now Kenya but what Chamberlain mistakenly identified as Uganda. Cockerell amusingly emphasizes the Home Secretary’s rather absentminded grasp of the geography of the Empire. As Herzl noted in a letter, Chamberlain’s mind was like a “big junk shop whose manager isn’t quite sure whether some unusual article is in the stock room.” When the territorial needs of the Zionists were explained to him, Chamberlain amiably indicated his willingness, in Herzl’s words, to “take a look and see if England has something like that in stock.”

Yet the “Uganda Scheme” proved to be fatally controversial and was overwhelmingly rejected by the Russian Jews at the 1903 Congress. For them, a Jewish homeland outside Palestine was inconceivable. Herzl himself had not been especially sanguine about an East African territory. Palestine remained his long-term goal, but the recent “dreadful outrages upon the Jews in Kishineff,” as Theodore Roosevelt put it, had redoubled his sense of urgency. Unfortunately, in July of the following year Herzl would be dead.

The celebrated English writer Israel Zangwill, later best known in America for his play The Melting Pot, was among Herzl’s collaborators. He is easily the most memorable of Cockerell’s characters, in part because of his ambivalence about the Zionist cause. Publicly, he was an active and articulate Zionist; privately, he mused that the most effective solution for the Jews might be complete assimilation, particularly in America. This scenario is celebrated in his play (first staged in 1908) when David Quixano, a young refugee from Kishinev, settles in New York and marries a Christian girl, Vera, who is also a Russian immigrant. Their union represents a symbolic reconciliation between Christians and Jews and points with almost ecstatic optimism toward a world—epitomized by the American experiment—in which all the ancient ethnic and religious hostilities of the Old World melt away.

The play was praised by Roosevelt but met elsewhere with withering criticism, especially from some prominent Jewish commentators. “We shall be melted whether we like it or not,” Bernard G. Richards wrote in The American Hebrew:

All our ancient traits and characteristics … shall vanish in the great process of the crucible. What spiritual identity will the Jew have when he emerges out of the ‘melting pot’? I infer from Quixano’s rhapsodies that the Jew will no longer be a Jew.

In his 1892 novel, The Children of the Ghetto: A Study in a Particular People, Zangwill had celebrated the traditions of the Eastern European Jews concentrated in East London, where Zangwill himself had grown up as the son of immigrants. Yet by 1913, he was openly calling for the mass immigration of Jews from the Russian Pale—not to Palestine but to America. There, the process of Americanization would bring to fruition the historical process of stripping the Jews of all those traits that had for centuries set them apart. “The Jewish people has been preserved almost exclusively by its religion, as a tortoise is protected by its shell,” he wrote in The American Hebrew. “With the decay of its shell, the organism it guarded must go.”

Zangwill’s schemes for mass Jewish immigration to the U.S. had begun not long after Herzl’s death when, in 1906, he broke with the Zionists and formed the Jewish Territorial Organization (ITO). In one public address, he asked, “What if, while our eyes are fixed trancedly on the closed gates of Zion, every other opportunity slips away forever?” The ITO explored a number of locales where an autonomous Jewish colony might be established, but all of these endeavors failed to coalesce until he began to engage in talks with New York banker Jacob H. Schiff, who never tired of pointing out that the true “Promised Land” of the Jews was America. “The Jew of the future is the Russian Jew transformed by American methods,” Schiff argued. He envisioned millions of Russian Jews abandoning their ghettoes to become “an integral part of a race of Americans yet in the making.”

Thus, the “Galveston movement” was born, a project that would transport persecuted Jews out of Eastern Europe and deposit them in a little-known port city on the Gulf Coast of Texas. Zangwill had misgivings. He stated repeatedly in interviews—even as he worked to move the Galveston plan forward—that American prosperity would rob the new immigrants of their “Jewish feeling,” and that America would be “the euthanasia of the Jews.”

Nevertheless, Zangwill argued that the ITO must “proclaim throughout Russia that “this immense territory is … largely empty.” Other American destinations for those refugees were considered, but the object was to establish a point of embarkation, a “melting point,” as it were, to facilitate the spread of the refugees deep into the American heartland. For this purpose, the port city of Galveston proved ideal.

Several key chapters in the middle of Cockerell’s book demonstrate that while the Galveston plan was not exactly an astounding success, it did accomplish, for the seven years of its existence, the resettlement of thousands of Russian Jews. On the Russian end, the project was managed by Cockerell’s great-grandfather, David Jochelman of Kiev, who had been a prominent ally of Herzl’s and was among the ITO’s founders. From his operational base in Minsk, Jochelman publicized the scheme, sorted through the qualifications of applicants, and arranged steamship passage for them in Bremen. According to Zangwill, the success of the “Galveston movement [was] primarily due to Dr. Jochelman.” But providing assistance on the Texas end was the prominent rabbi Henry Cohen, whose ties to numerous small Jewish communities throughout the middle South and Midwest allowed him to effectively place hundreds of refugee families and find them occupations. Many of their descendants still live in those communities today.

Jochelman is the lynchpin of the narrative, if only because Cockerell’s focus turns midway through the book to the fortunes of Jochelman’s descendants. At first this shift seems quite disconnected from the Zionist and ITO threads, but thematic ties do emerge. Several chapters deal with Jochelman’s son Emanuel, or “EmJo.” Born in Lithuania in 1898, he migrated at age 14 to New York with his father’s assistance, where he came of age on the lower East Side, living among those who had fled the pogroms. As EmJo Basshe, he began a career as a playwright and stage director in the 1920s and was closely involved with the so-called New Playwrights Theater, an avant-garde ensemble bankrolled by financier Otto Kahn, a well-known patron of the arts.

At least one of Basshe’s plays achieved a certain stature. Titled The Centuries, it powerfully captures the hopes and fears of the Jewish immigrants who dwell in a run-down tenement house. “They are absorbed into the life of Hester Street,” noted a review of the play in The Brooklyn Daily Times. “The whole life of the East Side eddies and swirls around them: pushcart peddlers, old clothes men, factory workers, cops, harlots, housewives, beggars, the rabbi.”

The immigrants in the play remain embedded not only in old customs but in the Yiddish speech of their origins, which, more than anything else, sets them apart from the “goyim, whose speech no man can figure out,” as one character laments. They long for the world they have left behind but somehow cobble out new lives for themselves. The play’s rabbi strives to prevent their assimilation, recalling how “the centuries have driven the Jews from Egypt to Palestine, from Palestine to Spain, from Spain to Kishinev, from Kishinev to Delancey Street to—the Bronx.”

Like Zangwill, Basshe seems torn between the close-knit culture of the ghetto and the New World promise of freedom and mobility, which will inevitably bring assimilation. Like The Melting Pot, Basshe’s play holds out hope, in the words of critic Kelcey Allen, “that as the emigrant attains material prosperity and moves away from the ghetto, his dissatisfaction with his American haven is decreased and he becomes assimilated.”

Eventually, Basshe married a gentile, a belle from Virginia named Doris Troutman, who mothered his daughter. Named after her father, the girl was always known simply as “Jo,” and it is her narrative (drawn from a series of interviews) that Cockerell gives pride of place in the book’s latter chapters, which are set largely in a rambling house in North London in the 1940s—a house purchased by David Jochelman and his second wife, Tamara Bach, after they emigrated to England in 1921. Throughout the ’20s and ’30s, Jochelman remained active in Jewish political affairs and was one of the chief organizers of the Jewish Protest Committee in 1933, which sponsored a major anti-Hitler rally in support of German Jewry. In those years, his two daughters, Fanny and Sonia, married and produced seven children between them, all of whom were raised in the North London house. One of these children, Michael Cockerell, was the author’s father.

Finally, perhaps the most striking thing about Cockerell’s fine book is the evidence it offers of the rapid loss of traditional Jewish identity that occurred over the course of several generations. By the time Jo Basshe left America in 1950 for a lengthy stay with her English family—bearing gifts of chocolate and chewing gum—she was thoroughly Americanized. She found the Jochelman household itself “totally immersed in being English,” with the partial exception of Sonia, who had married a Jew and still loved to speak Yiddish. But the Jochelmans were nonreligious, and even their attempts to observe Passover were marred by almost complete ignorance of the ritual.

Reflecting on this loss of Jewish inheritance, Jo says that her own father, who was buried in a Christian cemetery, “had shed it all.” For most of the family, the end of the British Mandate in Palestine and the establishment of the state of Israel were matters of indifference, though Sonia had promised her father before his death in 1941 that she and her husband, Yehuda Benari, would migrate to Israel if and when the Zionist dream was accomplished.

Yehuda was eager, but as Sonia admitted to her own daughter, Mimi, she was not terribly enthusiastic about the move. “She never was really a Zionist, but she could not stand the cold, and the thought of going to a hot country was just wonderful,” Cockerell writes.

As she does throughout her unique book, Cockerell presents such quotes with complete detachment, admirably making no attempt to influence the reader’s response.

Leave a Reply