Despite all that has passed since, the war of 1861-65 arguably remains the central event of American history. In proportion to population no other event equals it in mobilization, death, destruction, and revolutionary change. We are into the Sesquicentennial, and one would like to think that Americans will take the opportunity to contemplate where we come from and who we are.

Not likely, it seems. We will have instead an orgy of self-congratulation, regurgitation of old propaganda, blaming and guilt tripping, ludicrous comparisons with World War II, and an endless rehearsal of lucrative victimology over the “slavery” that ended more than a century and a half ago.

Historians and other commentators have expended a Great Lake of ink trying to explain the conspicuous deviation from the true American way represented by the Southern rebellion. I have always thought that the Northern way is more in need of explanation and should receive more close attention. It was the North that conducted a vicious war of invasion and conquest against other Americans, a thing previously unthinkable, and established an unprecedented regime of financial-industrial hegemony. But the American public long ago absorbed completely the weird contradiction of the Gettysburg Address in which Lincoln’s war was sanctified, at one and the same time, as a preservation of the sacred Founding and “a new birth of freedom.”

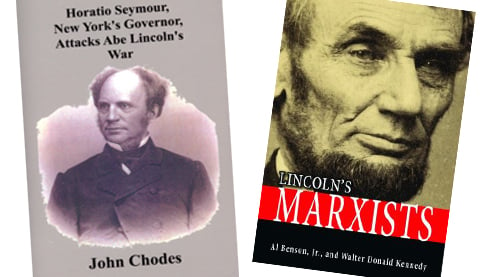

If anyone wants to pursue my quixotic line of inquiry further, there are plenty of places to do so. These two new books indicate that I am not entirely alone.

The Northern opposition to Lincoln’s war was much more widespread and more respectable than has been alleged. It amounted to a great deal more than a few treacherous “Copperheads.” This was documented ably in the works of the late historian Frank Klement, which works have been lost, it seems, down the memory hole. In truth, Lincoln and his party were never confident of the Northern public and often acted as an embattled minority in the North. Why else should the Army have seized newspaper editors, public officials, and ordinary citizens by the thousands and imprisoned them without due process of law? Why did Lincoln find it necessary to import more than 300,000 foreigners to beef up his armies against the fiercely resisting Americans of the South, while Northerners evaded the draft in even greater numbers?

The New York playwright and biographer John Chodes has illuminated one forgotten aspect of the war in the person of Horatio Seymour, governor of New York at the height of the war and Democratic candidate for president against Gen. U.S. Grant in 1868. The book is mostly a presentation of primary documents (always the best way to study history) that give us Seymour’s views before, during, and after the great crisis. He seems to have been a man of discernment and integrity, a sound-money man, anti-Know Nothing, an enemy of both Tammany and Republican corruption, and grandson of a Revolutionary general. The Republicans ejected him from the governorship in 1864 with a margin of slightly more than one percent—at a time when the New York City polls were under the control of the U.S. Army. The hero Grant in 1868 defeated him by a slightly larger margin, five percent, but then the entire Southern vote was a product of military occupation.

In January 1861, Seymour did not reject the possibility that Americans might govern themselves in more than one confederation. He deplored the Republicans who “cherish more bitter hatred of their own countrymen, than they have ever showed toward the enemies of our land” and their cavalier murder of the hallowed tradition of sectional compromise. On the imminence of a federal-government war against the South, Seymour wrote,

Can we so entirely forget the past history of our country, that we can stand upon the point of pride against states whose citizens battled with our fathers and poured out their blood upon the soil of our state. . . . Upon whom are we to wage war? Our own countrymen. . . . Their courage has never been questioned in any contest in which we have been engaged. . . . From the days of Washington till this time they have furnished their full proportion of soldiers for the field, of statesmen for the Cabinet, and of wise and patriotic senators for our legislative halls.

When the war came Seymour was eloquent against the illegal imprisonment of critics of Lincoln and against federal conscription, which he believed that the courts, if they were permitted to rule, would find unconstitutional. Chodes presents much material about the four-day battle between the New York militia and the U.S. Army, which has been misnamed the “New York City draft riots” and in which perhaps 8,000 New York citizens were killed by their federal government.

In November 1865, Seymour wanted to know, after a war of such magnitude and vindictiveness,

why the Union has not been restored? Why is it that we are told by a great party [Republicans] that the end for which our soldiers died and for which we poured out our resources, must be delayed. Now we are told . . . that the Union must not be restored until certain conditions are complied with, which were not demanded or brought to public consideration at an earlier stage of the contest. In 1864 I ventured a prediction . . . that when victory should crown our arms, it would be seen that the policy of those who assumed power in the administration was such that they could not bring back the Union.

He had known all along, of course, that the true Union could not be preserved by conquest but only changed into something else. As a presidential candidate, Seymour spoke eloquently in denunciation of Republican graft, legal and illegal, in the North as well as the South, and of the continuation of military coercion of the Southern states. It is useless to speculate what might have been had the humane Seymour won the election in 1868, but the course of American history might just have seen a “Reconstruction” better for everyone, North and South, black and white.

Among Lincoln’s Northern critics, Seymour was in fact moderate and cautious. Many respectable and intelligent men were much more plainspoken and vehement. (A work in progress by Chronicles contributor H.A. Scott Trask will bring this fact to light, while filling out an even larger part of the story of Northern opposition to the war.)

The early German settlers of America were peaceful and pious farmers, escaping militarism and religious strife. Not so the immigrants of the 1850’s, who were militarized advocates of violent social revolution, prototypes of later European communists and fascists. Revolutionaries and socialists on both sides of the Atlantic enthusiastically embraced Lincoln’s war as a continuation of the French Revolution and of their own failed revolutions of 1848. This is documented by Benson and Kennedy in full chapter and verse. The Forty-Eighters furnished at least four Union generals, several of whom were intimates of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and a host of colonels and Republican Party activists. The late-coming Germans may have made possible Lincoln’s election in 1860 by tipping the demographic balance in previously Democratic Midwestern states.

Marx, who knew even less about America than he did about everything else, described the conflict with the kind of grand abstractions that appeal to people of that ilk, even celebrating the rich corporation lawyer Lincoln as a hero of the working class. The Forty-Eighters did not dominate Lincoln’s party, but they were a very strong element within it. Nor did they necessarily have a complete picture, but all recognized that the Union cause was a step in their Marxist direction—an unappealable centralization of power combined with the violent destruction of reactionary elements. Since that time, their ideas have triumphed completely. Marx’s description of the war of 1861-65 as a defensive effort against violent reactionaries engaged in a wicked rebellion to spread slavery is now the mainstream p.c. interpretation, in the schools and media, of America’s central event.

These books remind me of what I consider one of the most revealing small incidents of American history. In his memoirs the Confederate Gen. Richard Taylor, son of a president of the United States and whose family had been in America since before the Mayflower, described how, upon his surrender, a German Union general, in halting English, informed him that now that the Southerners had been defeated, they would be taught the true American way.

Leave a Reply