Kenneth Miller, a professor of biology at Boston University, has produced a beautifully written work. His book is intended to refute every objection to the more or less universally accepted doctrine of evolution, to discredit its opponents, and to assert the compatibility of strict evolutionary doctrine with religion.

Ever since Darwin—and especially since the rise of Protestant fundamentalism early in this century—his opponents have launched attacks, some sophisticated but many of them heavy-handed, on the doctrine of evolution. During the last few years, a fresh series of literary assaults has been made, including books by a legal scholar and a biochemist, as well as political attacks, through the determination of school boards in Kansas and Kentucky that the teaching of naturalistic evolution in their schools will no longer be a requirement. In consequence, several promoters of evolutionary doctrine, Stephen J. Gould of Harvard among them, have mounted counterattacks to demonstrate that evolution (which for our purposes we shall call Darwinism, although evolutionary doctrine has subsequently progressed far beyond Charles Darwin’s views) is true, irrefutable, and indeed impossible for serious thinkers to doubt; also, that religious people need have no fear of it. Despite its title, which might suggest an inquiry into Darwin’s religious faith and theology. Miller’s book is devoted primarily to the defense of the man’s ideas—or rather those of his successors—which. Miller argues, are, scientifically speaking, absolutely sound. Starting with an anecdote about an early childhood encounter with what appears to have been the Baltimore Catechism with its straightforward and simple answer to the fundamental question of human existence (“Who made me?” “God made me”). Miller goes on to describe his early enthusiasm for the works of Milton, Dante, and other great literature, by comparison with which he found the Origin of Species plodding. It was not until, as a teaching assistant in college biology, he was confronted by a student waving a pamphlet entitled Evolution—the LIE that he became drawn into the defense of Darwinism.

Early in his book, Miller declares war on those evolutionists, such as G.C. Williams, who asserts that science has ruled out the existence of God, or at least of a benign one. “Is this indeed the case?” Miller asks. “Is it time to replace existing religions with a scientifically responsible, attractively sentimental, ethically driven Darwinism—a First Church of Charles the Naturalist? Does evolution really nullify all world views that depend on the spiritual? . . . And does it rigorously exclude belief in God?” He is definite in his response to his own question: “My answer, in each and every case, is a resounding no. I do not say this, as you will see, because evolution is wrong. Far from it. The reason, as I hope to show, is because evolution is right.”

Miller begins his defense of religion with the effort to demonstrate that Darwinism, in its modern form, is scientific truth and can withstand all attacks; he then proceeds to deal with the attackers, chiefly Philip Johnson and Michael Behe. In dealing with Johnson—the author of two books challenging Darwinism, Darwin on Trial and Reason in the Balance—Miller points out “that the case he and his legal associates bring against evolution is not a scientific case at all, but a legal brief The goal of his brief is to raise reasonable doubt . . . ” In order to prove a theory wrong, is it necessary to offer a correct alternative? Johnson has such an alternative—design by an intelligent Creator God—but his stated intention is not to prove the theory of biblical creation but to expose the fallacies of evolution. Johnson, poor fellow, is not a scientist. “His claim of a punctuated equilibrium falls apart under close scrutiny, and his assertions that the fossil record does not support evolution is in error.” Miller himself does not provide us with that close scrutiny. He merely asserts that Johnson is wrong.

Miller, a scientist rather than a lawyer or logician, argues, “If evolution is genuinely wrong, then we should not be able to find any examples of evolutionary change anywhere in the fossil record”—not noticing, apparently, that the existence of some examples of macro-evolutionary change, even if they are accepted (which not everyone is willing to do), does not prove the general theory of evolution: namely, that all present-day organisms came about through such change. And he does not acknowledge—although his position rather presupposes—the fact that the doctrine of evolution, even if it could explain how living beings came into existence, cannot deal with the question of purpose, of First Cause implying an intelligent Designer even more strongly, perhaps, than does the Cod of Genesis.

Miller devotes slightly more time to his fellow biological scientist Michael Behe, whose fundamental argument is that intelligent design is not merely possible but absolutely necessary. “Behe’s argument, as summarized in his 1996 book, Darwin’s Black Box, is that Darwinian evolution simply cannot account for the complexity of the living cell,” that biological life is made up of organs far too complex to have developed naturally. Against Behe, a geneticist. Miller resorts to what is called the genetic fallacy in logic: “As I read Behe’s book I began to get the impression that this seemingly new argument against natural selection had a familiar ring . . . At least for a while, many would fail to recognize just how old this argument really is.” Because, that is, the argument against Darwin is old, we don’t need to listen. Here Miller overlooks the fact that Darwin’s own theory must necessarily be older than arguments directed specifically against it. Of course, Darwinism is being regularly updated and modified—but without meeting the basic objections to it, as both Johnson and Behe would argue.

Among Miller’s arguments against intelligent design—and specifically against the theory (theistic evolution) that God Himself intervened in the evolutionary process to steer it and to speed it up—is his contention that, if God did so intervene, it would oblige Him to intervene in and to direct everything that occurs in the universe, and thus put an end to freedom, which Miller considers fundamental. Here is another case of the excluded mean: Why is it not possible for an intelligent Designer to design some things while allowing others to develop by chance?

Miller is obviously a benevolent man, one who does not wish to disillusion his students and readers or to destroy their faith. Unfortunately, the faith that he protects from Darwin seems a very pale substitute for orthodox religion. After quoting Darwin’s last sentence in the Origin of Species, Miller concludes with these words: “What kind of a God do I believe in? The answer is in those words. I believe in Darwin’s God.”

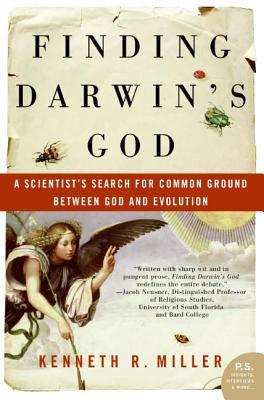

[Finding Darwin’s God: A Scientist’s Search for Common Ground Between God and Evolution, by Kenneth R. Miller (New York: Cliff Street Books/HarperCollins) 292 pp., $24.00]

Leave a Reply