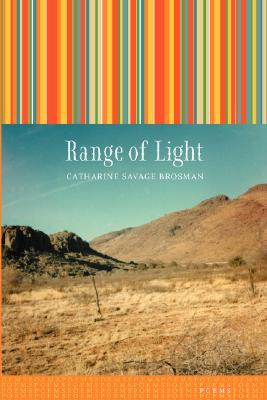

Range of Light, Catharine Savage Brosman’s sixth full-length collection of poetry, returns to the Southwest landscapes of the poet’s youth. It is impressive that Brosman has retained such a strong connection to her native region after an adulthood spent in New Orleans and a long career as teacher and scholar of French literature at Tulane University. Brosman’s verse is a rare example of good creative writing by an academic. The language of Range of Light is concrete yet musical, free of pedantry or critical jargon. This collection will appeal to readers who love poetry on nature and appreciate the unabashed sentiments of an artist who does also.

These 45 short poems can be read as the travelogue of a road trip that begins in Colorado and stops at all of the major national parks and towns of historical significance in the mountain states, eventually venturing into eastern California. Brosman emphasizes the unique physical features of each spot, describing them in precise geological terms and often explaining the geological history of rock and sand formations. Her explanations always move beyond the objective description of natural forces and invite the reader to find in these landscapes proof of the eternal power of nature as well as the harmony and power that infuse it. She sees the mud pots of Yellowstone as

. . . fantastic, as they flow,

with ferrous residue creating rings

and mineral wounds that bleed

against the snow.

It is enough for her to look at the moraines along the Snake River to understand that these rocks guarantee the reality of the Ice Age. Faithful guardians of the earth’s memory, “their heart is frozen as the glaciers / that reformed their rougher truth.” She readily makes very effective comparisons between sand and water. Deserts recall oceans in their color and movement, as in her description of Arizona’s Painted Desert, a coastline formed of sand but which now restrains a sandy sea:

. . . Just ahead begin the Painted

Cliffs,rippling in rose and sunset and ver-

milion,breaking the way the surf gives out,

then recommencing from the des-

ert swell.

Brosman consciously sets herself apart from the American poetic tradition, most notably represented by William Carlos Williams, that finds truth in an intense perception of objects that never dares interpretation. Brosman’s descriptions are exactly the opposite. She is personally involved with everything she sees, and her guidance renders this sight meaningful for the reader.

The Rocky Mountains reign over all these landscapes like a god. A vision of mountains frequently concludes a poem, as in the opening piece, “In the Abajo Mountains,” where the poet and her companions pour a libation of wine to the peaks that surround them. The mountain is often a slippery deity, only revealing its truth to the poet after a prolonged physical struggle. My favorite poem of the collection, “Enos Mills on the Divide,” tells of a climb during a winter blizzard when the narrator, accompanied only by his dog, scaled the icy face of a Colorado peak over two days, up to the Continental Divide. His reward is an experience of unity with earth and heaven, a renewal both spiritual and intellectual:

It was a birth

of consciousness: a continent

spread out,

broad-winged, two oceans of a bril-

liant white,and I embracing them, the only

mind.

Range of Light contains many pieces on plant life, but Brosman is at her best in her visions of high mountains and big skies.

Several poems are devoted to the explorers who opened the West for settlement—Indian scouts, French missionaries, gold prospectors, geographers, and soldiers. Brosman endows these explorers with a generosity of spirit derived from their tenacity but also from contact with the mountains. “In the Wind River Range” praises Sacajawea, the “Bird Woman” alone capable of guiding Lewis and Clark to the Pacific. “Stratton’s Gold” relates the rescue of a village by a Colorado prospector who cared nothing for the gold he mined: “it was the search / he wanted—courtship, hunting challenge . . . ” “La Glorieta” commemorates the accomplishments of a Colorado cavalry brigade that stopped the advance of Confederate troops at a New Mexico mountain pass. The narrator, a survivor of the battle, muses on the soldiers’ motivations and concludes:

We barely knew ourselves—still

less, the war’sideals. I think that history, in fact,

is not so plain . . .

So petty reasons surely held that day,

But great ones too . . .

All of these figures seem unselfconsciously heroic. Finding themselves in situations as extraordinary as the lands they inhabit, they acted spontaneously and became positive forces in American history. Brosman is unapologetically fascinated with these characters whom some might consider pillagers of the land and invites the reader to pay attention to their importance in the development of the Southwest.

At the center of Range of Light, Brosman places several poems on Taos, New Mexico, and its artist and writers’ colonies. These contain some of the most humorous moments in the trip west, as the poet, in her attempt to understand the creative energy associated with Taos, finds that the tourist industry has laid claim to art. She visits Kiowa Ranch, refuge for D.H. Lawrence and Georgia O’Keeffe, in the company of an “old curmudgeon” of a guide, who has only “a very imperfect understanding” of the artist he speaks of. Even worse, O’Keeffe’s house has become a convention center complete with a huge parking lot that “holds a hundred campers, cars, RVs, packed in rows / as for a tailgate party.” Without anger at these insensitive invaders or nostalgia for the time when Taos was not a celebrity spot, the poet nevertheless understands that she must visit these places alone and concentrate on the nature that inspired such great painting and literature. The skyline of Taos Mountain so admired by Lawrence can still give the sensation of the mythical phoenix ever reviving from its ashes and ascending into heaven:

. . . a bird of indigo

emerging from the ashes, winging

upward, calling outwith hieratic voice and flashing

blue among the clouds.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s work affirms the artist’s power to release the spiritual force of common objects: “She knew the meaning / Of the everyday for them, a metaphysics / realized / as in the visible, as in her canvases.” “Taos Hymn,” the masterpiece of this section, celebrates this unusually perfect city but also the art created in its confines with religious respect:

So may these artifacts of earth

remain as evidence of worth,

attesting to creation’s art

and holy deserts in the heart

whose blue horizons blaze to fire

and shimmer with divine desire,

God held in azimuthal ken,

Redeeming us and world. Amen.

The native peoples of the Southwest appear more and more frequently in the second half of Range of Light. Brosman knows a great deal about American Indian history, writing about several tribes, from the prehistoric Anasazi to modern Hopi and Zuni. Although she does not meet a single living Indian in her travels, their presence permeates the landscapes she visits, and she acknowledges the spiritual superiority of these peoples who respected the land and knew how to live in harmony with nature. She finds evidence of their religious practices and cultural traditions everywhere. The ponderosa pine is a “Shaman still.” Winds blow over mesas like “Kokopelli’s flute,” the magical instrument of New Mexico’s legendary humpbacked musician. “Dust Devil” transcribes a transhistorical moment. The poet faces a landscape that has not changed from the earliest days of mankind to the present:

. . . The Anasazi, also, watched the

stratusdrape the mesa tops and anticlines,

wingeast to sail among great monolith-

ic birdsof black basalt, or hover, moored

by stillness.

She points out the connections between Native American and European cultures. Navajo weavings, like the tapestry of Odysseus’s Penelope, record the dreams of a beleaguered people and express a love of land and family. The petroglyphs adorning canyon walls are religious symbols as reverential as sculptures in a cathedral:

. . . the holy sign,

of how the universe and men en-

gagedtogether in their sacred motions

. . .

This mythic treatment of Southwest Indian artifacts and culture conveys their importance in this land while avoiding sentimentality and picturesqueness.

The title Range of Light has a double meaning. It refers to the entire Southwest and its varied inhabitants; it is the “range” of the traditional folk song, spiritual home to the poet and inspiration for her poetry. Brosman celebrates this land with sustained enthusiasm. Whether she is poised at the Continental Divide or contemplating a cresting river, she expresses gratitude for these places where mortality does not matter since, as she says in “Conejos Rising,” “we’ve got a gorgeous view on life from here.” The title also alerts us to the importance of light imagery in these poems. Brosman concentrates on the unusual lights, such as “the blue-flame sky” unknown to city-dwellers, the brilliant snow of the Rockies, the sharpness of moon and starlight on nights that are never cloudy. She is sensitive to the peculiar effects of light on the sands, which have the reflecting power of water, or of sunlight streaming through thin leaves that resembles rays coming into a cathedral from a stained-glass window. Desert plants create a prismatic effect in a deceivingly uniform desert for the discerning eye. Like Georgia O’Keeffe, Brosman recreates the strong colors and sharp lines of this unique region to highlight even the simplest objects, such as berries and cactus thorns. Light imagery buttresses the sense of a spiritual or intellectual illumination that concludes most of the poems in this collection. The poet grasps a similarity between her situation and that of ancient peoples or experiences a moment outside of time, in perfect union with the physical world:

. . . mind

becoming what it held a moment:

spacetree, mountain, fire—the journey

and its end as one.

Like Dante, whose influence she acknowledges in “Mud Pots,” she translates these moments through light, illumination offering the closest analogy to ecstasy.

In Range of Light, Brosman writes in both rhyme and blank verse. There are occasional lines of free verse, usually at the beginning of a poem, but iambic pentameter is the dominant rhythm. I have quoted these poems at length to give an idea of the strong meters which Brosman adapts to description, philosophical reflections, or humor; to technical terms, geographic names, and emotions. The musicality of this verse adds to the pleasure of encountering the Southwest through the eyes of a lover of the land, its rich culture, and history.

[Range of Light, by Catharine Savage Brosman (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press) 62 pp., $17.95]

Leave a Reply