To put this volume in perspective, we have to know that the cartoonist was a young amateur who actually considered making a career of the art, but was then drawn to another mode of expression—one which transcended, perhaps, her cartoons, but also sublated them. They were always a part of her imagination; the habit of art could be transformed into the world of her fiction, and it was.

And also for the sake of perspective, we have to remember that the artist died at the age of 39, nearly 50 years ago, which means in effect that we have been thinking about her—if that is the case—longer than she thought about us. As the author recedes into history, she looms larger not because she possessed a gift, but because the gift possessed her.

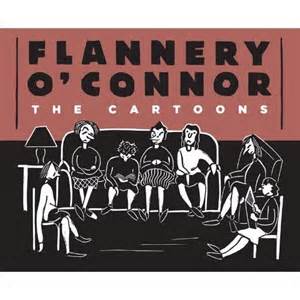

Perspective suggests furthermore that this is another in a line of extraordinary volumes by Flannery O’Connor (1925-64) that were created by editors who, in one way or another, synthesized various materials. Robert and Sally Fitzgerald were responsible for Mystery and Manners (1969), which pulled together various essays, speeches, and other prose. The Complete Stories (1971) put the apprentice stories written for O’Connor’s M.F.A. at the University of Iowa in context for the first time. Sally Fitzgerald gathered and edited O’Connor’s letters as The Habit of Being (1979), which some have thought O’Connor’s greatest work. The Presence of Grace and Other Book Reviews by Flannery O’Connor, edited by Leo T. Zuber and Carter W. Martin, gathers a decade of reviews written for two diocesan newsletters. A more oblique book such as Arthur F. Kinney’s catalog of O’Connor’s personal library (1985) is authentic and valuable, and so are certain other works of biography, analysis, and bibliography.

O’Connor herself, of course, was responsible for the publication of Wise Blood (1952), A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955), The Violent Bear It Away (1960), and the posthumous Everything That Rises Must Converge (1965), which she addressed on her deathbed. And Sally Fitzgerald edited the compendious volume published by the Library of America (1988), which seems now—not to put too fine a point upon it—to be quite possibly the greatest single volume ever written by an American. So what we have seen over the years is not only an extensive, even international, response, but also an enhancement and expansion of the record and the definition of it.

I well remember discussing with Sally Fitzgerald, years ago, the idea that O’Connor was always working, so that everything in her experience and her imagination was fused. That is why the extension of our sense of her consciousness has been particularly justified. This is also the case with O’Connor’s cartoons. So having said so much, I will say more. The cartoons that the young O’Connor produced and caused to be published in high school and in college were a large part of her life—in context, they were much of her social life—and they were also training for the future and what became her vocation. She was the vortex of the scenes she observed and overheard, and she became the creator of their satirical transformation into cartoons that are miniature, minatory, funny, and even grotesque.

About the cartoons themselves, everyone will have what today’s students call “their own opinion.” The cartoons do not, as they strike my eye, have the instant mastery and command demonstrated by such luminaries of The New Yorker as John Held, Jr., James Thurber, Peter Arno, George Price, Charles Addams, and George Booth. Flannery O’Connor as cartoonist operated one notch down from their level of achievement. But she was very good indeed, and the cartoons gain stature and earn affection with acquaintance. Let me add at this point that O’Connor submitted some of her cartoons to The New Yorker, which rejected them. So she herself entertained grand comparisons. But the magazine never recognized her as the great short-story writer she was in later years, either, and even maintained a ban on the mention of her name in subsequent decades.

Be that as it may, the artist Barry Moser has in his Introduction defined for us the status of the linoleum print as O’Connor exploited the medium, working fast and with coarse technical means. He is as objective and informed as he can be, and he respects O’Connor’s achievement with her cartoons. But he also knows that they are connected to aspects of her personality that existed before the cartoons and after. Because of his particular credentials, his take on the graphic artist is both pertinent and necessary.

Kelly Gerald’s Afterword, “The Habit of Art,” is also an informed and productive statement, and a more extended one. She insists on the unity of O’Connor’s imagination from the age of five until the end. O’Connor had always been fascinated by birds, by her own sense of the absurd as well as of the divine, and she always worked at expressing a vision. Fitzgerald notes that O’Connor stayed in touch with the visual arts after she quit cartooning by “painterly” passages in her writing, by her painting itself, and by her casual and extemporaneous drawings in her private correspondence. Kelly Fitzgerald’s summary of a comprehensive vision is a commanding exposition of the O’Connor phenomenon, and the best treatment of O’Connor and the visual arts ever penned—the last word of this remarkable book.

So there it is. Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons is not for everyone, nor was it intended to be. But it is for everyone who wants to know about O’Connor the person, as well as O’Connor the creator. That is much, but there is more. The book is not only by far the best statement about, as well as a complete and flawless presentation of, the cartoons; it is also the best treatment of any kind having to do with the young O’Connor in high school and college during World War II. After she finished her college work in three years, she was off to graduate school in Iowa, where she found herself in a new way. She left cartooning behind, but never her sharp eye, nor the literary possibilities of physical comedy and caricature.

Leave a Reply