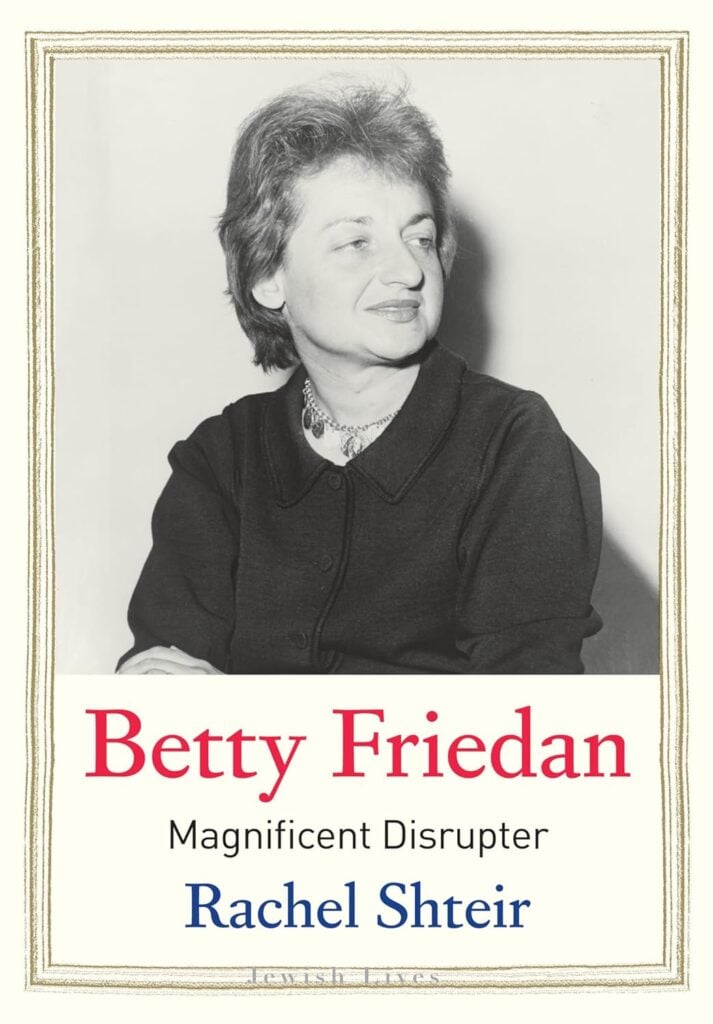

Betty Friedan: Magnificent Disrupter

by Rachel Shteir

Yale University Press

428 pp., $27.00

This Betty Friedan biography is likely to be the last. Today, the story of her life and career is an inconvenient and unwelcome reminder of a past that many feminists would rather forget.

But give plucky Friedan biographer Rachel Shteir full marks for trying to make Friedan into an American hero. She dubs her a “magnificent disrupter,” borrowing the phrase former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi used to describe Friedan back in 2006.

From the standpoint of 2024, however, it’s not clear exactly what was so “magnificent” about Betty Friedan. She may have been a gifted writer, but she had the mentality of a Pravda editorialist and a temperament so quarrelsome that it stood out even amidst the feuding that characterized the post-World War II American women’s movement.

For the many Americans who today may not recognize the name, Betty Friedan was born Bettye Goldstein in 1921 in Peoria, Illinois, “on the right side of the tracks,” as Friedan herself observed. Tabbed at an early age as “brainy,” Friedan “grew up with the triple burden of being intelligent, unattractive, and Jewish,” a writer noted in 1976. Friedan later studied psychology at Smith College and Berkeley. She was a largely unknown wife, mother, community organizer, labor columnist, and writer for women’s magazines when, in 1963, she published the best-selling book that elevated her to national prominence, The Feminine Mystique. The book sold 1.4 million copies and, according to the writer Alvin Toffler, “pulled the trigger on history.” Friedan herself said The Feminine Mystique “catapulted me into a movement of history.”

The Feminine Mystique is mostly legendary for introducing the phrase “the problem that has no name,” a condition, Friedan alleged, that afflicted millions of married American women. Based partly on a survey she completed in 1957 of her former Smith College classmates, The Feminine Mystique argued that women felt “a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning” that could not be satisfied by their roles as wives and mothers. Women’s genuine self-actualization was achieved outside the home and the family. And the solution, according to Friedan, was “work important to the world, the work that used women’s human abilities and through which they were able to find self-realization.”

Friedan’s claim she was discovering something new, however, was a myth. Women’s magazines such as Redbook and Good Housekeeping ran stories throughout the 1950s about the frustrations, yearnings, and anger some married women felt as they tried to live up to the domestic ideal. Nor was Friedan’s contention that she spoke for all women true. Polls at the time revealed that more than two-thirds of American women believed family decisions should be made by the “man of the house.” When McCall’s magazine ran Friedan’s article titled “The Fraud of Femininity,” the magazine was deluged by letters from angry female readers who objected to her message that their lives were empty and wasted.

Nonetheless, press coverage of The Feminine Mystique paved the way for Friedan to, among other things, co-found the National Organization for Women (NOW), the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), and, in 1971, the National Women’s Political Caucus. By then, Friedan was one of the most familiar faces in America. She was a media star, appearing at protests, political rallies, picket lines, and on TV talk shows. During Nixon’s presidency, the liberal press lavished praise on her and her defense of abortion on demand and equal pay for equal work.

But in retrospect, 1970 was a watershed year for Friedan. That year, she played the key role in the nationwide Women’s Strike for Equality, attracting tens of thousands of women around the nation. But it was also in 1970 that lesbians denounced her at a NOW conference over her very open discomfort with their presence in the movement’s ranks. She may have had obscure personal reasons for calling them “the lavender menace,” but she never hid her belief that including lesbians in NOW would alienate a lot of American women otherwise attracted to the movement. The backlash over her comments on lesbianism led to her departure from NOW’s presidency.

As the 1970s wore on, her star continued to fade. Shteir blames “cruel media coverage” for printing “unflattering” photos of Friedan. Even Friedan’s first biographers admitted her “brusque manner, impatience with others, and easy irritability” drove wedges through the early women’s movement. She sparred with feminist luminaries Gloria Steinem and Bella Abzug, calling them “female chauvinist boors.” Author Germaine Greer called Friedan “tiresome” and overrated as a feminist pioneer. Other feminist critics attacked her for focusing on middle-class suburban women and denounced her belief that race was less important than sex when it came to the discrimination black women faced. Black writer “bell hooks” called Friedan’s book “a case study in narcissism.”

The 1970s ended with a whimper for Friedan, when her campaign to win passage of the Equal Rights Amendment petered out. By 1973, the U.S. Congress and 30 states had approved the ERA, and the movement needed only eight more states to pass it. Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter backed the ERA and numerous celebrities endorsed it. It looked like a done deal, until activist Phyllis Schlafly ran a grassroots campaign to stop it. When the two debated in person at Illinois State University in 1973, Friedan got so angry with Schlafly’s claim that American women were “the luckiest class of people on earth,” that she exclaimed, “You are a traitor to your sex. An Aunt Tom. And you are a witch. God, I’d like to burn you at the stake.” This and other events of the campaign took the wind out of the sails of the ERA movement, and ultimately it finished three states short of approval.

Then there was her disastrous marriage with theatre producer Carl Friedan. They raised three children but fought constantly and often violently. On at least one occasion, Betty showed up at a public event with black eyes. But even Shteir admits that the story of the Friedans’ raucous marriage is “not just about Carl-as-domestic-abuser.” Once Betty was seen chasing Carl down Fire Island’s beach while brandishing a knife. The couple divorced in 1969, and Carl later said that she hated men. “Let’s face it, they all do—all those activists in the women’s lib movement,” he said.

Carl always challenged the belief that Betty was an emotionally starved housewife in their home when writing The Feminine Mystique. He claimed “she had time to write it because she lived in a mansion on the Hudson River” and “had a full-time maid.”

Then came the revelations of historian Daniel Horowitz who, when researching his 1995 book on Friedan, began poking around in her past during the 1940s and 1950s. As Horowitz discovered, she frequented communist and fellow-traveling circles in Berkeley in the 1940s, at one time dating a CPUSA member and student of physicist Robert J. Oppenheimer. Once she even applied to join the Stalinist CPUSA (she was told by a party member that she was more valuable to communism outside the party). As a labor journalist, she later wrote boilerplate stories for communist publications such as UE News and the New Masses. When Horowitz asked Friedan for permission to quote from unpublished materials, she responded by denouncing him and threatening to sue.

There are other reasons to suspect Friedan was covering up her communist past. By introducing the phrase “the problem that has no name,” Friedan was borrowing without attribution ideas that she had already encountered in those circles. Until the advent of McCarthyism in the late 1940s, left-wing writers capitalized on the good press Stalin’s Soviet Union enjoyed during the war to celebrate the alleged status of women in Communist Russia. For example, the American marriage counseling pioneer Emily Mudd, based on a highly-staged 1946 tour of the Soviet Union, sang the praises of Soviet women, whose work outside the home supposedly made then more fulfilled. Mudd and other fellow-travelers openly urged America to follow the Soviet model as a way of addressing the deep unhappiness American wives allegedly felt in their own marriages. Thus, long before Friedan introduced the country to “the problem that has no name” left-wing opinion-makers were talking about the same phenomenon and invoking Stalin’s Russia as the blueprint for emancipating America’s wives and mothers. Friedan never cited these sources, but it is scarcely imaginable that she knew nothing about them.

Friedan’s last years, Shteir admits, were mired in embarrassing public “score-settling” with her ex-husband Carl and the “women’s liberationists” of years gone by. On her death in 2006, luminaries such as Nancy Pelosi stepped forward with perfunctory accolades, but the sad truth is that she had gone from feminist pioneer to inconvenient fossil within a few short years. The movement she once bestrode careened in weirder and weirder illiberal directions and disowned her time and again.

The temptation for conservatives is to mistake Friedan’s splenetic run-ins with others in the women’s movement as the misfortunes of a “moderate” feminist. Indeed, Christina Hoff Somers argued in her otherwise admirable 1995 book, Who Stole Feminism?, that Friedan was a “liberal” who sought “individual justice for all.”

But Friedan was no “moderate” and she never shed her intolerant communist mentality. If she bequeathed anything to later generations, it was her tendency to engage in awkward hyperbole, especially by comparing 1950s suburban housewives with the inmates of a Nazi concentration camp. Her attacks on lesbian activists in the women’s movement may strike conservatives today as courageous, but they should never forget that, though she was a “disrupter,” she was hardly “magnificent.”

Leave a Reply