This is a difficult time to be a Catholic. The moral scandals in the Church, which should have provided an occasion for constructive change and for replacing the leftist American hierarchy with bishops of strong faith, pure morals, and sound theology, have only aggravated the divisions within the Church. Even many self-described traditionalists are taking advantage of the crisis to say “We told you so.” Nothing good has happened since the elimination of the Tridentine Mass (which, of course, has not been eliminated), they say, and even Paul VI’s encyclical Humanae Vitae has been condemned by Latin Mass, a magazine that recently seems to have taken on the task of reducing Catholic moral theology to the principles of capitalism. Pope Leo XIII, St. Thomas Aquinas, and every other major doctor of the Church must now make way for Adam Smith and Bill Gates.

In their rage and frustration with the very real disorders in the Church, some traditionalists do not hesitate to say that the See of Peter is vacant. Only their saving remnant of old believers represents the true Church. Like other American conservatives in these troubled times, many Catholic traditionalists are afflicted with a shortsighted perspective on the Church and a crippling ignorance of history. It is not, after all, as if the Catholic Church has not faced equally grave crises in the past, some of which were over theological errors that threatened the very core of the Faith. Anyone who says (as some traditionalists do) that the dangers of the Arian heresy “pale in comparison” to current problems must know very little of Arianism.

Other crises involved scandals that were at least as outrageous as the current one or persecutions that dwarf any of the imagined sufferings of the schismatics in the St. Pius X Society: the ancient bishops who recanted their faith or surrendered their Scriptures and sacred vessels to Roman officials; the persecutions under Decius and Diocletian, followed quickly by the Arian persecutions; the terrible reign of the harlots of the tenth century and the disgusting Renaissance popes (notably Leo X, Julius II, and Alexander VI); the persecution of the Church by French liberals, whose mistreatment caused the death of Pius VI, and by Napoleon, who captured and abused his successor, Pius VII. When Pius IX was elected, liberals around the world called him the “last pope” (a name that had also been applied to Pius VII). The liberals were premature.

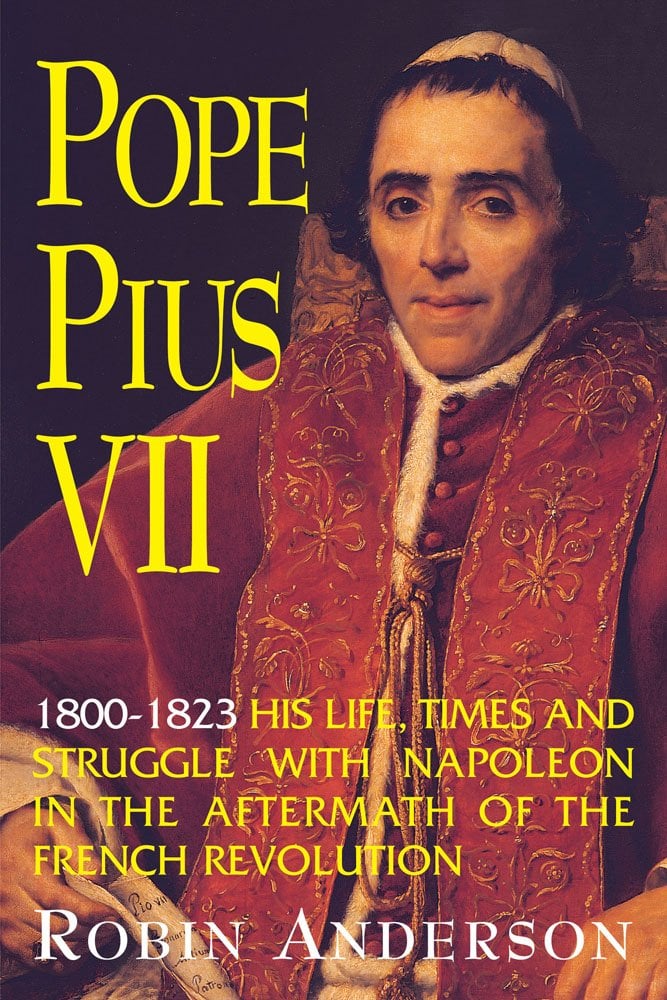

Naive and sentimental traditionalists seem to think that, before Paul VI, there were no bad popes. Robin Anderson knows better. A stage manager and writer, Mr. Anderson converted to the Catholic faith and moved to Rome, where he has worked as a speaker for Vatican Radio. He is the author of a number of popular books on Church history, including one (privately circulated, alas) with the provocative title Crisis Popes. His new life of Paul VII is a timely reminder of two important facts: Good popes are not perfect, and even the best of popes may have a difficult time steering the Church through an age of crisis. Though not a scholar, Mr. Anderson has covered the major written and documentary sources (most of them in Italian, French, or Latin), and he tells his story with clarity and vigor. He quite properly admires his subject and can be pardoned if he sometimes refuses to be entirely objective.

Barnabas Chiaramonti, the future pope, was born to a distinguished noble family in 1742. As a student, he was exposed to the infectious germ of Jansenism (the Calvinistic and holier-than-thou hypermoralism that seems to beset many American traditionalists), but, in his adult life, he succeeded not only in throwing off whatever Jansenist influence he might have imbibed but even in restoring the Jansenists’ mortal enemies, the Jesuits. This was not a trivial accomplishment: Despite the current degeneracy of the Society, the Jesuits were in the forefront of the fight to maintain the traditions of Christian moral theology.

Ordained and entering the Benedictine order as Father Gregory, Chiaramonti (not without distinguished supporters) rapidly rose to prominence, becoming bishop (and cardinal) of Imola in 1785. There, he came face to face with the French Revolution. In 1796, Bonaparte entered Milan and proclaimed his intention of marching on Rome to liberate the people of Italy from papal oppression. Though a treaty was signed, Pope Pius VI was taken prisoner, and the old man was subjected to such mistreatment that he died a prisoner of the French.

In Imola, Cardinal Chiaramonti—as brave as he was prudent—learned quickly that open resistance to Bonaparte could only bring misery and suffering to the people. He had a hard time of it, doing his best to defend the Church and the Christian religion while, at the same time, restraining the hotheads whose intemperate actions brought swift retaliation. Elected Pope in 1800 and taken prisoner in Rome by the French in 1809, he was to apply those hard-won lessons throughout his papacy.

Pius VII was an unflinching opponent of everything the French Revolution stood for, but he was also a Christian who understood that Napoleon was not a demon but a man, perhaps even a great man. Pius’s greatest diplomatic triumph was the Concordat of 1801, which restored the Catholic Church in France. Bullied, threatened, and deceived by the French emperor, the Pope consistently sought the best terms he could, both for French Catholics and for the Church as a whole. He faced down Napoleon’s violent rages with calm detachment. In 1813, the emperor was determined to force the Pope into signing a second Concordat that would give the emperor effective control of the Church. Arriving at the Pope’s chamber in the evening—dressed absurdly in a hunting costume to show how casual he was being about the whole thing—Napoleon stormed and raged at the Pope’s refusal. “Times have changed,” he shouted, repeating himself, “times have changed! The Church must adapt and be reconciled with the Revolution.” Pius VII preserved his composure and dryly commented on the imperial performance: “Comedian,” he told the emperor to his face.

The Pope’s moment of weakness came during this struggle. He eventually was persuaded (under false pretenses) to sign the false Concordat, which he later repudiated. For his heroic resistance to the French tyrant, Pius VII was lauded by the Protestant allies and lionized in England, and yet, when Napoleon fell, he refused to gloat. At the fallen emperor’s request, he sent a chaplain to St. Helena, and the Pope, during the period of Napoleon’s second and final exile, used to meet with Bonaparte’s mother in Rome, where he consoled the poor woman by talking with her of “the good Emperor.” Through his confidant and secretary of state, he declared the Church’s indebtedness to Napoleon, to whom was owed (after God) the credit for “the reestablishment of religion in the great kingdom of France”:

The dutiful and courageous initiative of 1801 made us long forget and forgive subsequent injuries. Savona and Fontainebleau [where Pius VII had been imprisoned] were but actions of a misled mind, aberrations of human ambition; whilst the Concordat was a saving act undertaken in a Christian and heroic spirit.

The reactionaries of those days, however, were bent on revenge and resisted every attempt to reform the government of the Papal States. If a pope could not give them exactly what they wanted, then so much the worse for him. Throughout the 19th century, such great popes as Pius VII and Pius IX—the men who, after God, saved the Church—were denounced as liberals. It was an age of tribulation for the Church: two popes held captive by the Jacobins and another, Pius IX, attacked and rabbled in Rome and deprived of the Papal States by the anti-Catholic liberals who created modern Italy. In hindsight, however, we can see that those were also glorious days for the Church, who took Her stand against the heresies of modernism without taking refuge behind the walls of the Vatican.

A little knowledge of this episode in Church history might take some of the smugness and contempt out of the self-proclaimed saving remnant that is doing so much damage to the traditionalist cause, and Robin Anderson’s biography is an excellent place for them to begin their Catholic education.

[Pope Pius VII, 1800-1823: His Life, Times and Struggle With Napoleon in the Aftermath of the French Revolution, by Robin Anderson (Rockford, IL: TAN Books) 219 pp., $16.50]

Leave a Reply