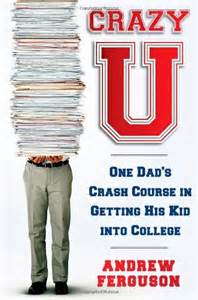

“Crazy U?” Or “Crazy Me?” A self-deprecating Andrew Ferguson must at least have been tempted by such a title. His self-absorbed son (and what 17-year-old isn’t?) would surely have agreed, had he been remotely aware of the grief that the whole insane matriculation process was causing his father.

Certainly, the elder Ferguson did have his share of humor along the way. He also “learned a lot.” Those three little words are usually uttered by a D student who is pleading for a C, but in Andrew Ferguson’s case it happens to be true.

Ferguson learned, for example, that it’s one thing to bone up on the history of the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and quite another to take the exam when you’re 30-plus years past your SAT-taking prime. That embarrassment aside, he also learned that colleges initially adopted standardized testing in the name of such laudable goals as objectivity and fairness, and that colleges are now abandoning such tests, or placing minimal emphasis on them, in order to achieve fairness and, of course, diversity. Ferguson isn’t convinced that a test-free admissions process is necessarily a good thing. Moreover, he finds it more than slightly odd that the old Harvard of legatees and jocks, frat boys and failures, geniuses and jerks, was in many respects more intellectually diverse, and in some respects more culturally diverse, than its modern counterpart.

This business of harvesting a diverse crop of similarly minded freshman can be very tricky indeed—so tricky that many exclusive colleges now use what they like to call an “holistic method” to select the fortunate few. The serendipitous quality of this process, coupled with the relative scarcity of seats in such schools and the absolute bonanza that awaits many of their occupants, has led to the creation of an “only in America” growth industry, represented by firms that charge exorbitant fees to help families negotiate the admissions game by offering a crash course for parents looking for an edge in securing a spot for their offspring in a wildly overpriced college.

Two reliable sources convinced Ferguson that the term “wildly over-priced college” is a laughable redundancy. The first is Ferguson’s own experience with tuition sticker shock. The second is Ohio University’s Richard Vedder. An authority on the economics of the modern American college, Vedder drew on his dual reservoir of expertise and cynicism to inform an about-to-be-fleeced Andrew Ferguson that colleges charge what they charge because “they can.”

High tuition is also a function of the fact that colleges now masquerade as country clubs. Colleges do what they must to provide the amenities necessary to attract clients, who then pretend to be students. On a related matter, Ferguson learned that the popularity and profitability of U.S. News & World Report’s college guide enabled a once-great magazine to keep up pretenses somewhat longer than would otherwise have been the case. Ferguson also learned that college officials must at least feign indifference to, if not pose as opponents of, any ranking system—unless their own college happens to score high marks, in which case they have to pretend that the results were as fair and accurate as their admissions processes.

All this knowledge should earn Ferguson at least a C for his efforts. And if such a grade should prove damaging to his GPA (Good Parent Assessment), he can always claim that he learned a lot. Still, there were moments in his “crash course” when it appeared to Ferguson that the whole thing was about to implode. Such a moment surfaced whenever it became painfully obvious to the parent that he was much more interested in the whole thing than was his son. Another arrived when Ferguson senior began to weigh the current cost of a college degree (as opposed to a college education, but who cares about that?) against his ability to finance it, not to mention his recurring suspicion that the value of said degree would ultimately “collapse under the weight of its own unreality.”

What to do, he wondered out loud to another concerned, college-obsessed parent, otherwise known as a fellow member of the “Kitchen People”—parents who gathered occasionally to commiserate with one another, lie to one another, and otherwise trade war stories about a campaign that began, innocently enough, in late summer with the arrival of glossy college “viewbooks” before climaxing in early spring with letters of acceptance—or rejection.

Along the way, Andrew Ferguson had moments when he seemed to come to his senses. Maybe he ought to “drop out of the bubble” and steer his son toward a “discount (community?) college.” Too horrible a prospect to contemplate? Then how about a year away from school entirely, either to perform the volunteer work that high-school seniors routinely lie about on their college applications or—heaven forbid—do real work for real pay? Maybe then, and only then, would his son begin to think seriously about what he wanted to do with his life. But that option, too, was finally unthinkable. Apparently, Andrew Ferguson did (and does) believe that the truly unthinkable course of action would have been to abandon the pursuit of finding just the right college, no matter the wildly inflated price, and no matter the absence of much interest on the part of anyone in what was actually being taught—or learned—in any college.

A somewhat ghostly figure in these pages, the junior Ferguson simply presumes that college is his next step, and the bigger and glitzier the college, the better. What soon-to-be 18-year-old male wouldn’t leap at such a prospect? After all, these days colleges are 60 percent female. Actually, he seems an agreeable enough sort whenever he makes a cameo appearance in what is essentially his father’s story. One such appearance occurs during his stab at writing, and even rewriting, the obligatory application essay. Not that his father failed to play the expected role of contributing editor. In fact, here the elder Ferguson approaches his best. The proposed topics were either absurd, sophomoric, or solipsistic—or all three. One draft of the resultant essay was so chaotic as to constitute, in the editor’s words, a “verbal version of his bedroom.” The essay author’s estimate was not entirely dissimilar: “[I]t’s a bunch of bullcrap.”

Having learned so much, Andrew Ferguson is prepared to do little more than throw up his hands and laugh at the whole shebang. Having exposed the bubble, he refuses to prick it—or walk away from it. Is it too much to hope that others will read this book and either vow not to play the college game or work seriously to change it?

We can only hope that other parents will succeed where Andrew Ferguson failed. Colleges might finally get the message if enough of us actually did “drop out of the bubble” by offering our children four tough choices: get a job, hit the road, find a soup kitchen, or take a seat in a local “discount” college. The alternative is total war on a system overflowing with money and overrun with professors and administrators who could stand a good dose of the very self-deprecation that leaves Andrew Ferguson stranded somewhere in midair, musing about our national educational predicament, puzzling over it, laughing at it, while hoping against hope that he will survive the next four years without being too badly fleeced by an unnamed Big State University, and that his dear son will somehow escape, degree in hand, without being too badly miseducated along the way.

Leave a Reply