There have been dozens of books and hundreds of articles written about Flannery O’Connor (1925-64) in America alone, and considerable attention from overseas as well. Indeed, R. Neil Scott’s new Flannery O’Connor: An Annotated Reference Guide to Criticism describes 3,297 books, articles, dissertations, and master’s theses by 2,474 different authors. Though she died at age 39, O’Connor (perhaps like Poe and Chopin) made an extraordinary impact that is still felt. Her posthumous publications (stories, essays, reviews, letters, addresses) and the film renderings of her works have greatly extended her presence, while the publication of her collected works in a volume of the Library of America in 1988 perhaps fixed her reputation. She was the second woman so honored (Edith Wharton was the first), and the first born in the 20th century. Riffing through all the pages of that library, we may well conclude that, word for word, the O’Connor volume is the single most distinguished in the entire series. Toughski luckski, Edith. Tant pis, Henry James.

Owing to the explosive nature of her fiction, much of the attention that O’Connor has received has been either perplexed or indignant. Sensitively attuned to the Zeitgeist, O’Connor set herself against it insofar as it contradicted the theological depth she knew from her Catholic faith. That faith, as she emphasized, was not merely a given but was always under construction. One of the merits of Jean Cash’s biography is to show how open O’Connor was to experience and to people.

The very notion of a biography of O’Connor, however, is striking for several reasons. Hers was a life in which, ostensibly at least, there was a lot that didn’t happen. The lupus that she developed early on, and the drugs she took for it, kept her at home. Since marriage was out of the question, she formed a domestic partnership with her mother and was devoted not so much to her work as to the cultivation of her vision. And this leads to another reason why a biography should be remarkable.

The Habit of Being, the edition of O’Connor’s letters as edited by Sally Fitzgerald and published in 1979 preempted a biography to a large degree. In themselves, the letters amounted to an epistolary autobiography, and some have even thought that volume to be O’Connor’s greatest work. And there is yet another “lion in the path,” as Henry James put it: For years, Sally Fitzgerald assembled information toward an authorized biography, but that project was incomplete at her death in 2000, and its future is unclear. Jean Cash, who thus worked as an unauthorized biographer, has done much in terms of scholarship and interviews to flesh out her portrait of Flannery O’Connor.

To her credit, she has gotten right some essential points that needed to be clarified. One is that Flannery O’Connor, even as a child, was set apart by her distinctiveness and her capacity for wonder, and her superior intelligence was always obvious to her teachers and her peers. Another is that, though we always picture O’Connor at home in Milledgeville, Georgia, she would not have lived there had it not been for the disease that finally killed her. Full disclosure requires that I acknowledge Cash’s quotations of my parents and myself; full disclosure also requires me to add, however, that I have still not seen a completely satisfactory account of O’Connor’s highly restrictive relationship with her immediate environment.

Jean Cash has treated O’Connor’s and her mother’s attitudes toward blacks in a way that seems to me both anachronistic and unnecessary—though she has not had much to say about O’Connor’s attitudes toward lower-class whites, present in so large a part of her work. Cash has felt herself obliged to respond to the feminist critique of O’Connor and to deny that O’Connor was a lesbian, which also seems unnecessary. And she has not only opened the door to speculation about what O’Connor would have become had she lived longer but supplied the answer in the form of a quotation from a feminist critic: “If Flannery O’Connor had lived long enough for the feminist movement to arouse her awareness of society’s injustices to women and of her own repressed rage, surely she would have confronted these problems consciously in her stories.” Though this hypothesis seems unaligned with anything we know about O’Connor from within or without Cash’s biography, such thoughts suggest others. I am convinced that, if Flannery O’Connor had lived long enough to become more aware of exercise, nutrition, and Oriental philosophy, she would surely have discarded her cumbersome crutches, worked out in a modish jogging outfit, eaten tofu, and meditated in the lotus position.

However that may be, Jean Cash’s biography reminds us of O’Connor’s clarity of mind, that sense of perspective with which she overwhelms her readers. The sense of elevation or revelation, seeping through homely material and crafted as a vision that is beyond time, retains its authority. Flannery O’Connor’s works, in their ironic balance, are still imposing and, ultimately, comic, no matter how painful they are to her protagonists. The biographer has demonstrated the possibility that the artist, in her person and in her effect on others, was greater even than the works into which she inscribed so much of herself.

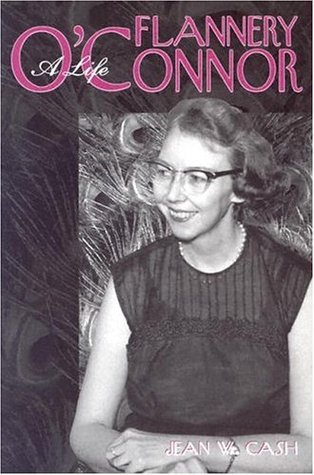

[Flannery O’Connor: A Life, by Jean W. Cash (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press) 356 pp., $30.00]

Leave a Reply