“Literature is news that stays news.”

—Ezra Pound

Seeing Raymond Chandler published in series with Edgar Allan Poe and Mark Twain and Flannery O’Connor might give us pause. But not for long, for Raymond Chandler himself told us what to say on this occasion, writing the lines for that delectable secretary, Miss Vermilyea, in Chapter 11 of Playback (1958), as she encounters the detective/ narrator Philip Marlowe for the second time: “Well, well. Mr. Hard Guy in person. To what may we attribute this honor?” Since, as Marlowe puts it. Miss Vermilyea was quite a doll, I think we could and should specify to what we may attribute this honor.

Strictly speaking, the honor was earned in the only direct way that counts: Chandler has never been out of print and is widely read today in many languages. He is continually referred to as a standard reference, imitated ad infinitum, and is a constant presence in the mass media. All the Chandler movies are rebroadcast on cable—the ones that he wrote, the ones others did, and all the recreations and extrapolations. To say “film noir” is to conjure Chandler—”neo-noir” ditto. Without Chandler, the journalists would be without their catchphrases, “the mean streets,” “The Big Sleep,” “The Long Goodbye.” Without Chandler, S.J. Perelman and Woody Allen would have had that much less to parody. Without Chandler, Chinatown and Blade Runner would have been unimaginable, Larry Gelbart could not have written City of Angels, and Ross Macdonald and John D. MacDonald and Robert B. Parker and Lawrence Block and Sara Paretsky and Sue Grafton and Walter Moseley and many another would not have given up their day jobs.

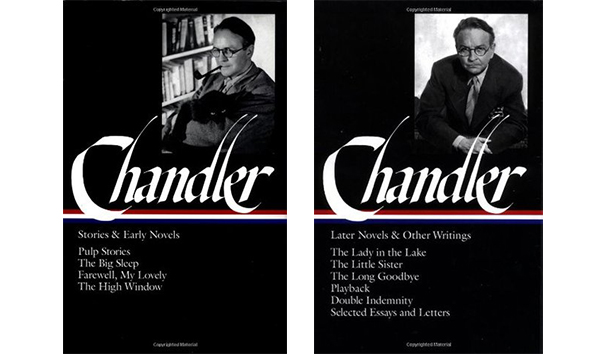

Though Raymond Chandler himself saw to it that he exploited his power in the movies and on radio and television, he knew very well that his appeal rested on a literary achievement. Since his time, critics such as Philip Durham, Jerry Speir, and William Marling have written solid works about that achievement. Chandler’s letters have been published in two different editions, two of his screenplays have appeared, and his life has been the subject of a formal biography. In addition. Chandler has been the object of considerable academic attention in the form of dissertations, theses, articles, and studies. J.K. Van Dover’s The Critical Response to Raymond Chandler (1995) nicely summarizes the decades of increasing recognition. But surely the ultimate accolade has been the publication of the present elegant volumes.

Quite an honor it is. To behold and to hold these two volumes is to embrace old friends, but also to recognize that Philip Marlowe and his .38 revolver are hanging out with some highfalutin company. The hard-boiled dick is taking tea in the parlor with Emily Dickinson, and holding forth with Hawthorne and Melville and James. The news is that those treasured old paperbacks, their pulp paper disintegrating and their lurid covers fading, have been definitively republished in acid-free paper and sewn bindings to last for generations. Marlowe and his crowd—Eddie Mars and Moose Malloy, Velma Milento and Terry Lennox, Weepy Moyer and Dolores Gonzales, not to mention Miss Vermilyea—are now up there with Hester Prynne, Captain Ahab, and Christopher Newman in the Library of America, a scries modeled on the French Pléiade. As the eponymous scarlet letter orbits with the Brasher doubloon, there is a fulfilling sense that Marlowe’s creator, Raymond Chandler, had always aimed at the stars.

When Chandler began, he aimed high—that is to say, in the best way to do so—by first aiming low. The story of Raymond Chandler’s life and literary career is one of the most remarkable in the history of American literature; and though it is familiar, it is worth repeating. Conceived in Laramie, Wyoming, and born in Chicago in 1888, Raymond Thornton Chandler was soon exiled by his parents’ divorce to Ireland and England. His secondary education at Dulwich College, with its emphasis on Latin and Greek, marked him for life with a keen sense of language and class. Though soon set up with a career in the civil service. Chandler dumped his job and tried to live as a literary bohemian—his accomplishments of those days, such as they were, have been collected by Matthew Bruccoli in Chandler Before Marlowe (1973). Chandler’s literary aspiration, sense of exile, and ambivalence between the bourgeois and the bohemian, were already in evidence in Bloomsbury before World War I.

After returning to America, winding up in Los Angeles, and serving in the Canadian army in the war. Chandler began to rise as an executive in the oil industry. He married Cissy Pascal, 17 years his senior, after her divorce and his mother’s death. The great crisis of his life came when he lost his lucrative job during the Depression, and decided to commit himself to writing in his middle age. He aimed high by aiming low when he accepted the demands of the marketplace: he would write for Black Mask and Dime Detective, beginning in 1933. He would write within the conventions of the hard-boiled school, but he would find a way to elevate and transform those conventions.

Since many of Chandler’s stories of the 1930’s were subsequently “cannibalized” for his novels, the editor of the Library of America’s Chandler set, Frank MacShane, has published those that were not later transmogrified. The best of these stories show how Chandler brought poetry to the pulps, romance to realism, and literariness to popular entertainment. Chandler’s three best stories are ostensibly about pearls, and show that before his novels he had already mastered the art of transcending the genre of the detective story. “Goldfish” (1936) is a straightforward tough-guy investigation which at the end makes us wonder whether the pearls are fakes. In “Red Wind” (1938), Chandler’s fully developed art is both melodramatic and self-referential, and the pearls are finally fakes of fakes. “Pearls Are a Nuisance” (1939) is Chandler’s most extravagant venture into what Keith Newlin has called “hard-boiled burlesque.” The fakes are real, and the self-mocking fakery of the narrative is “real”—a parody of investigations and languages, both cozy English and tough American. The “pearls” that all the fuss is about are Hitchcockian Macguffins, for the word pearl not only denotes five-point type but is also derived from the Latin perua, meaning “ham,” Chandler thus slyly acknowledged that writing comes from writing, that writing is in some sense about its own composition, that he was hamming it up, and that he owed something to Dashiell Hammett. The split between the Anglo gent and the American tough guy in “Pearls Are a Nuisance” reflected Chandler’s literary and social realities, and was incorporated in the double consciousness of Philip Marlowe, who did not appear until Chandler’s first novel, The Big Sleep (1939).

The Marlowe novels were a big step up for Chandler, not only in terms of the extension of his aims, but also commercially and literarily: Philip Marlowe first saw the light of day in hardbound, published by Knopf. The Big Sleep, Farewell, My Lovely (1940), and The High Window (1942) led directly to Hollywood, the big time and the big bucks. Twice nominated for an Academy Award, Chandler was not happy in Hollywood, and took it for all he could. MacShane has included Chandler’s collaboration with Billy Wilder, the screenplay adapted from James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity, but we should note that Chandler’s original screenplays for The Blue Dahlia and Playback have previously been published. MacShane has included in this collection, however. Chandler’s essay “Writers in Hollywood,” which still stands up very nicely. He has included as well other essays and 11 of his letters. The only question one can raise about MacShane’s choices, I think, has to do with the space taken up by the collaborative and derivative screenplay. Eliminating it would have made room for 100 more pages of Chandler’s fascinating letters. As it is, however, the Library of America edition is a handsome and deserved recognition of a compelling writer.

Of course it was as a writer, not as a hacker of detective yarns, that Chandler wanted to be recognized. That is exactly what so many of his letters are about, and indeed what his novels are crafted to show. Looking back at those novels today, we can see perhaps better than ever just what it meant to stake a reputation on writing itself, on style, rather than on what that writing purports to represent. But to see that means clearing away partial truths that, whatever their merit, limit our vision of Chandler, his books, and their continuing life.

One such limiting truth is that Chandler was a regionalist—that he virtually created Los Angeles. And of course we remember the powerful sense of place that Chandler vividly projects. Nostalgia addicts flock to such books as Edward Thorpe’s Chandlertown (1983) and Ward and Silver’s Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles (1987) and even the “Raymond Chandler Mystery Map” for that very reason. But the old Los Angeles is long gone and was going even as Chandler limned it, as he emphasizes in The Little Sister (1949). But going on and on about the Santa Monica pier and the Bradbury Building only proves that what Chandler gave us was on the page and not on the street, just as Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County was and is his property—one not to be confused with Lafayette County, Mississippi. Chandler’s El Lay is a literary/mythological trope, not a place, and the best map of it is provided by T.S. Eliot in The Waste Land, in which the Unreal City is figured as a desert. Fisher Kings are not hard to find in Chandler’s pages, though they may not be easily identified in the Los Angeles White Pages.

That leads us to another and more powerful limiting truth: Chandler as a writer of quest romances or urban Gothics, in the main tradition of American literature. Seen in this light, Marlowe has something in common with Natty Bumppo and Huck Finn and the frontiersman. And it is quite true that Chandler fortified his novels with chivalric imagery. But even here we must remember that Chandler’s romances were ironic ones, with bitter and frustrating endings. Marlowe finds no holy grail—usually he finds a dead sinner. Another limitation of the American romance model is that Chandler was himself not entirely an American. The Long Goodbye (1954) hints at the international novel, just as Chandler in his last days spent as much time in England as he could.

Raymond Chandler himself insisted on another limiting and contradictory truth—namely that the Marlowe books were “realistic.” Considering their contrivance, their status as lurid melodramas, their conventional coincidences, we must find it hard to accept them as realistic. But he probably meant two particular things by his use of the category of realism; first, that his books were hardboiled and not cozy; and second, that they reflected the truth about power in urban America. The implications of that second thought have never been fully examined, but they will be.

I think that today Raymond Chandler’s work can be seen most fruitfully as writing, and not as representation. The extent of his ambition can be glimpsed in his allusions to Shakespeare, Eliot, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald, but it can be seen most fully in his rich language—his similes and ironies, his wit and sense of beauty, his puns, anagrams, and etymological teasings. His discourse refers to itself continually—his writing is about writing, and it is a celebration of writing’s power to make us laugh, make us shudder, make us think, make us wonder, and make us turn the page. That power of writing was Chandler’s, and he knew it and said so. That power he called “magic” and “music.” That power is the ultimate reason why Raymond Chandler has been canonized.

That power earned Chandler something greater than the considerable amount of money he made by it, and something even greater than the present recognition. That something is fame. Billy Wilder has declared that when people ask him questions about Hollywood, there are two names that are always mentioned first: Marilyn Monroe and Raymond Chandler. Monroe’s title as “sex goddess” speaks for itself, but Chandler’s charisma was achieved by performance on the page. Such a glamour is today a global, not a national, property; and indeed “Raymond Chandler” has been a character in at least two novels. He is truly a “man of letters” in all the languages and all the media of civilization. No wonder he claimed that he had taken “a cheap, shoddy, and utterly lost kind of writing, and . . . made of it something that intellectuals claw each other about.”

Chandler was a novelist all along, and not a scribbler of detective stories—just as he claimed. He gave us every indication of his detective’s repudiation of his job. In The Big Sleep, Marlowe “catches” the killer in the beginning, literally. At the end, he finds futility in having pursued a man who was not his case and was already dead. In Playback (1958), he tells his client to go kiss a duck and is lost in dreams of bliss. Chandler called Marlowe “the personification of an attitude,” and so he is. That attitude, I think, was one of Protestant individualism and decency staring in bemused horror at the depredations of modern mass culture. The illusion of literary “realism” was in parallel with the illusion of a new society: the fraud of self-transformation offered by the new mass-cult and exploited by the ruthless. Marlowe showed he was part of the problem in The Little Sister, by which gesture Chandler acknowledged the same about himself.

The Marlowe books, retaining a diagnostic and prophetic quality, are no more dated than literature is. According to the classical formula, they delight and instruct. Marlowe is more poet than detective, and is more interested in pursuing the Other than in earning his fee. Chandler pushed Marlowe into the ultimate of literary abysses in his last three novels, having him confront the illusion of film itself and of reality in Hollywood (The Little Sister), the illusion of writing with a novelist in the novel (The Long Goodbye), and the illusion of fiction when a stand-in for Chandler himself walks on stage to meet Marlowe (Playback). That is not the stuff of whodunnits, but of a Shakespearean sense of illusion within illusion—the stuff that dreams, and literature, are made of.

Having survived their own day for two generations, Chandler’s novels have earned their status as classics in the simplest possible way. But by the time that Raymond Chandler drank himself to death in 1959, his own body (as distinguished from his literary corpus) was misplaced. Because of various confusions, that wealthy and famous man was buried where the indigent are interred in San Diego. I would like to think that Chandler has received, finally, a proper sendoff in the Library of America. In these pages, he is more than ever before recognized as a writer—and his work will continue to live by being read in a context far removed from the pulps where he began. But that distance is exactly what he did imagine—and justify. In that sense, we can say with the poet, “Here he lies where he longed to be.”

[Raymond Chandler: Stories and Early Novels, Edited by Frank MacShane (New York: The Library of America) 1199 pp., $35.00]

[Raymond Chandler: Later Novels and Other Writings, Edited by Frank MacShane (New York: The Library of America) 1076 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply