The decline of the household economy is one of the most significant economic changes in post-World War II America. Unfortunately, it has received relatively little attention. Professional economists find it trivial compared to the workings of large-scale institutions and global economies, while the average American sees only a positive development that has meant greater mobility, money, and freedom from menial labor. However, the seemingly benign death of the household economy has produced serious social ills. The New Agrarianism makes the connection between them explicit. Once human labor is removed from its ancient objects—the household, the community, and the land—a social pathology of cynicism and destruction ensues. To overcome it, modern agrarians advocate more socially intimate ways of living and working, ways that are also resource-efficient and aesthetically pleasing.

Contemporary agrarianism builds upon a long tradition of agrarian radicalism in Western history going back to ancient Greece. In recent times, agrarian thinkers have represented a wide range of political and philosophical opinion. Whether from right or left, however, they have virtually always operated outside the political and intellectual mainstream. Throughout the 20th century, agrarianism has been strongly identified with social and cultural conservatism. Eric Freyfogle, in his Introduction to The New Agrarianism, reviews the last several generations of agrarian thought, making ample reference to the contribution of the Southern Agrarians, the English Distributists, and such latter-day agrarians such as Richard M. Weaver and M.E. Bradford. Like their forebears, contemporary agrarians are deeply conservative with respect to economics and community life. They are also suspicious of social engineering and progressive views of history. Naturally, their view of social change is incremental rather than revolutionary. However, modern agrarians spend less time than their predecessors did in describing the virtues of past agrarian civilizations: Theirs is a more practical response to the contemporary problems of urbanism, industrialism, and consumerism. As such, they are less political than older generations of agrarian writers. They are also less inclined to defend agrarianism in the name of Western civilization and its religious and cultural traditions.

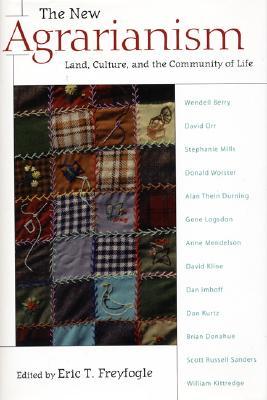

The pieces assembled in this book represent some of the best agrarian writings of the last dozen years. Many of the writers are farmers, others scholars and teachers, but almost all are experienced practitioners who live the life they preach. Freyfogle has collected 15 essays on a wide range of topics, from the virtues of agrarian life to practical issues. The first section, which accounts for almost half of the book, is the most substantive. Beginning with a piece by Scott Russell Sanders, who profiles agronomist Wes Jackson and his pioneering work on a type of sustainable agriculture patterned on native biocommunities, this section introduces the reader to agrarian ideas expressly designed to be put into practice in a world dominated by big business, big government, and the consumer culture. In a similar vein, small-scale farmer Gene Logsdon points out the fallacies of “bigness” in agriculture, explaining that it has nothing to with efficiency but is, rather, all about power. Logsdon’s own practices have consistently shown that small operations are more efficient and more ecologically sound than larger ones. Environmental-studies professor David Orr concludes the section with a critique of the modern city, in which he advocates better design as a means of creating more sustainable ways of living. This requires not only new practices but a whole new set of concepts. Unfortunately, Orr argues, the language to disseminate agrarian ideas and others promoting an ecologically sustainable agriculture has not been fully developed, especially when compared to the powerful vocabularies that have grown up around sex, technology, and consumerism.

Section Two, presenting critiques of modern industrial culture, is summed up by environmental historian Donald Worster in his concluding piece, “The Wealth of Nature,” in which he debunks historian Lynne White’s now infamous argument that Judeo-Christian civilization is responsible for modern environmental problems. Instead, Worster sees their root in a materialist philosophy that had its greatest expression in the ideas of Adam Smith. Worster’s way out of the materialist morass, although vaguely stated, is a return to a more holistic and spiritual way of life. The book ends with accounts of people who have lived successfully as agrarians, the most illuminating being that by Amish farmer David Kline, who provides impressions of his own life, which is based on simplicity, faith, and hard work. The book’s most poignant essay, however, is Wendell Berry’s “The Whole Horse,” a rejoinder to Allen Tate’s famous “Half a Horse” metaphor in I’ll Take My Stand, in which Tate laments the abstraction and spiritual incompleteness of modern society. Berry emphasizes that the whole horse can only come into being in an agrarian culture. He also reiterates one of the Southern Agrarians’ main points: Agrarianism is not just about agriculture; it is the economic counter to industrialism. Berry ends with a paradox, asking why conservatives and conservationists are not closer allies since both groups are deeply passionate about defending what is most severely threatened by modernization: traditional society and the natural world in which it struggles to survive.

While the main focus of all of these writers remains the family farm, they are concerned more broadly with the separation of all work from the home. It is not just farming but virtually every economic activity that has been abandoned as a family enterprise—-–from cooking and cleaning to sewing and child-rearing. Thus, it is no accident that, with its collapse as a unit of economic production, the household has been transformed almost completely into a unit of consumption. Once self-reliant, the household today is dependent on the market for its very survival. In this economy, work is no longer a spiritual or ethical pursuit but a means to wealth and status. (For most Americans, it is simply a way of increasing consumption.) The tragedy, of course, is that people must now spend more and more time working away from home in order to maintain their consumption levels. Many do not even eat at home anymore; home has been reduced to a rest stop where we watch television and sleep.

The consumer cancer affects nature as well, from the obvious despoliation of land, air, and water to the more subtle impact on human health. Perhaps the most noticeable health problem in America is obesity. Americans are the fattest people on earth, perhaps in all of history. Much of the reason for this has to do with the mechanization of our society, in which machines have largely replaced human labor. But obesity is also linked to the collapse of family farms. Today’s large farms overproduce. They are so productive, in fact, that they can be enormously wasteful and, at the same time, produce enough to keep food prices low. Low prices, coupled with an ever-expanding menu of tasty items, have created an American food culture that can only be defined as orgiastic. Food is no longer about nourishment; it is a form of entertainment. For the refined, eating is a dining experience; for the masses, a means to overcome boredom. Sadly enough, eating is one of the last connections modern man has to nature. Like sex, it has been so thoroughly severed from the process of life and death that it has become perverted. When food was connected with survival, it was celebrated. Eating was a spiritual act: People prayed over their food to express communion and to thank God for the privilege of being able to eat. But saying grace seems almost absurd in a society that can split atoms, splice genes, and supply a thousand varieties of snack food.

The basic argument of The New Agrarians is that, if the gap between production and consumption can be reduced, American families will be able to recover a modicum of economic sovereignty and sanity. By refocusing on the importance of household economics, agrarians are not seeking to inaugurate an agrarian Golden Age but to create a viable economic alternative to bloated and bureaucratized capitalism. The main philosophical principle underlying agrarian economics is the idea of social subsidiarity. Only when simpler forms of human organization and technology fail should more complex forms be called upon. With a dual emphasis on small-scale organization and private property, an agrarian economy is probably the closest thing to a truly free market. Such an economy may not produce great wealth, but it does foster strong and stable communities. It also allows economy and ecology to merge more closely than in any other economic philosophy. Unlike modern environmentalism, however, agrarianism views the physical environment as more than a playground or an aesthetic experience. Nature is where man lives and works. And, since nature is the cycle of life and death, it is treated with respect.

Unfortunately, one issue that this book and other recent agrarian writings have shunned is the obvious connection between the collapse of the household economy and mass migration. As capitalism expanded, American men and women left the household and the farm to pursue greater wealth and convenience in the city. And, as the household came apart, its components were readily commercialized on a mass scale to form much of what is commonly called the “service economy.” The all-too-familiar result is an economy comprising huge national chains in food and dining, cleaning and washing, and—sadly enough—child and elder care. Even garage sales and flea markets have been economically standardized and nationalized. (What, after all, are Wal-Mart, K-Mart, and Target but corporately run bazaars?) What is omitted from this analysis is the condition that the mass consumer economy requires an equally massive body of cheap labor to perform the dirty, degrading, and often dangerous work that all of these industries depend on for their survival—agriculture especially and, in particular, the meat industry, where human laborers and animals alike suffer from appalling conditions. Most of these laborers are immigrants, legal and otherwise. A greater reliance on self and family to supply economic needs would reduce the hoards of servant-slaves that Americans now depend on to sustain the lifestyle of maximum consumption.

This is one of the social costs of the modern capitalist economy, whose chief goal is expansion. As the juggernaut races across the globe, it obliterates all competing economic models in the quest to create a unified economic system—a total economy. The cultural losses of the process are all too familiar, yet agrarians argue that they cannot be separated from the material changes that modernization has wrought. Excessive reliance on technology and large institutions has abstracted humans from nature, which has led to nature’s radical misuse. Agrarians want to change this situation. By returning to old-fashioned thrift, coupled with a greater dependence on the family and local resources, people can reduce their reliance on Leviathan. Based as it is on material minimalism, this idea amounts to a radically conservative approach to economic and social life. This dispensation, moreover, is inherently spiritual, inasmuch as it is under such conditions that the mind is ultimately freest to think, to imagine, and to pray. The agrarian economy is the moral economy, precisely because it allows our humanity to express itself most fully.

This is a compelling reason why paleoconservatives must make agrarian principles central to their economic and social philosophy. Failure to do so will keep these ideas at the social margin or, worse, allow them to be appropriated by the left. If that should occur, agrarianism will have become just another progressive idea, in which rural living is simply seen as one more alternative lifestyle threatened by “conservative” capitalism.

[The New Agrarianism: Land, Culture, and the Community of Life, edited by Eric T. Freyfogle (Washington, D.C.: Island Press) 256 pp., $40.00]

Leave a Reply