Everyone in the Western world writes from left to right, so Michael Novak’s title is more cute than revealing. The subtitle, on the other hand, makes a claim: that he moved from at one point in his life being a liberal to an admission that, sometime before he reached his present octogenarian state, he was willing to take on the burdensome label of conservative. My sainted aunt, who did everything she could to mold me into a New Deal progressive, also used to paraphrase many wise people by saying to me, “A man who is not liberal before the age of 30 has no heart; and a man who is not a conservative after 30 has no brain.” Michael Novak tries to show us, in this engaging memoir, that he had both a heart and a brain when he was writing left, and when he was writing right.

The flow of this intellectual autobiography is from left to right, and “I revisit the lessons I learned the hard way.”

Events and facts forced me to change my mind about the ideas with which my education imbued me, eager pupil that I was. I worked out my changes of mind publicly in articles and books. As my new direction became clear, I lost many close friends. My phone stopped ringing. Angry letters from dear friends pleaded with me to desist. I was shunned at professional meetings, even by the closest of old colleagues. Some refused to appear with me ever again on any academic program. This was a common experience among those of us who moved from left to right in our time.

His description makes the transition sound dramatic, as if he had a Saint Paul moment on the road to Damascus. Actually, it was slow and measured. The Reagan presidency had something to do with it: “I loved the Reagan presidency. You could feel the whole aircraft carrier executing a broad turn on the ocean, moving the nation in a badly needed direction.” It is not hard to imagine his former friends aghast at a Reagan-lover, but Novak was still voting for Democrats in the 90’s, and he still has good things to say about President Clinton. Why, then, a shunning?

No doubt it was because of his most famous book, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism (1982), wherein he horrified his friends on the left by arguing for what he had been hinting at for a few years. From the leftist position that “Any serious Christian must be a socialist,” he was ready to declare in 1976, “A Closet Capitalist Confesses” (in the Washington Post!). Novak’s economic journey, typical of most of his intellectual transformations, was triggered by the empirical decision that socialism did not, and never had, worked. Sociologist (and neoconservative) Peter Berger influenced his reading of the “social sciences,” and Novak attributes his newfound empiricism to the kind of thinking Berger was doing (originally as an anticapitalist exercise) in the 1970’s. This would be typical of Novak’s changes of mind: A leftist position derived from what he perceived to be his cultural heritage and the conviction, born of his religion, that we must care for the poor and respect “universal human rights” gradually undermined by hard thought, neoconservative arguments, and the hard lessons of reality, landed him eventually somewhere on the right, a traitor to the chattering classes.

It should be noted that Novak never has been particularly interested in economics, nor will he ever become a libertarian or even a man overly friendly to the free market. Rather, he says, “Culture comes before economics.” His “full-blown theory” is that “a good society is composed of three interrelated systems: cultural, political, and economic, each depending on the others; each checked and balanced by the others.” Capitalism, he eventually decided, is “the least bad system,” more than others conforming to man’s limited and sinful nature, a conclusion that eventually caused him to suspect that nanny-state politics would not help the poor any more than socialism and in turn led him to abandon the political nostrums of men whom he had admired and worked hard for in the 60’s and early 70’s: the Kennedys, Sargent Shriver, Gene McCarthy, Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Novak never had much interest in Lyndon Johnson or Jimmy Carter, and while he liked George McGovern immensely he didn’t think much of him as a politician. After 1980 or so he was drawn to Reagan, Jack Kemp, George Bush I and II, Bill Clinton, Steve Forbes, and Lady Thatcher.

By temperament, Novak was always rather conservative. This was part of his heritage. His Slovakian working-class Catholic family, although union people and Democrats, were not in any meaningful sense progressive. The Novaks had strong faith, strong families, strong belief in the value of work; and while they may have carried a working-class chip on their shoulders toward the rich and the business classes, they generally believed that there was opportunity for their sons in America. Michael spent 14 years preparing himself for the priesthood, and although he experienced a dark night of the soul concerning his vocation, he never had a deep crisis of faith. He had, and retained, rather amazing self-discipline, he loved and married and held onto one woman, and sooner or later he tired of every cultural fad of the 1960’s. This is not the stuff of leftists. It is more the culture of the “Reagan Democrats” who changed American politics in the 1980’s. Both this memoir and his writings over the years demonstrate how attached Michael Novak has remained to his ethnic and cultural heritage.

Novak celebrates two important intellectual influences who profoundly affected his transition from seminarian to lay Catholic. Gabriel Marcel, the French “existentialist” philosopher and playwright, “fanned the sparks in me of a lifelong interest in the ‘person’ . . . [which] means an individual being who is conscious, choosing, and self-directing.” To Novak this was different from the atomistic individual, and had meaning in “the exchange of personalities that occur in everyday life, in the encounters to which we are open with others.” The joy this notion gave him, both when he was a liberal celebrating the idea that the “person is always becoming,” and after he had moved right to find that “community springs only from honest argument,” has stayed with him the remainder of his career. His other major intellectual influence was Reinhold Niebuhr, on whose “Christian Realism” Novak wrote his doctoral dissertation. “I wanted to model myself on Niebuhr in two chief respects,” he says: “his realistic resistance to utopianism, and his habit of unmasking the pretensions of elites—in particular, the so-called political reformers.” Since both men voted with the left, they seemed to fit Novak’s temperament and his Christian optimism.

It has apparently not occurred to Novak, despite his gradual reawakening to the reality of sin—original and otherwise—that his “unmeltable” ethnicity, existentialism (however defined), and left-voting Christian Realism might present very serious obstacles to the acceptance of a true conservatism. They did, however, help him to put up a shield against ideology. His list of “conservative” friends after moving to Washington and the American Enterprise Institute (dinner companions, mostly) includes Ben Wattenberg, Mort Kondracke, Midge Decter and Norman Podhoretz, Bill Bennett, the Weigels, the Kristols, the Krauthammers, and others who would be widely recognized as the heart of neoconservatism, along with the Buchanans and the Borks and cosmopolitan conservatives like Robert Nisbet and Clare Boothe Luce. While I would enthusiastically welcome all of these brilliant and interesting people to my table, most of them are hardly what readers of this magazine would consider conservative. Even Novak’s friend Mary Eberstadt admits that “Michael Novak is a quintessential neoconservative.”

Yet there is his Catholicism. Speaking of Vatican II, he says, “my first movement from left to right began in religion.” Of all the places “Providence” could have put him after graduate school, the first was Rome during the council of the Church that upset Western culture more perhaps than the Pill or recreational drugs did. In fact, in this book, culture (which “trumps politics and economics”) is virtually synonymous with religion. Novak says almost nothing about the arts or literature (why read Weber and Tawney and Hayek when he could have been rereading Dante?), while the two most revealing and important chapters in the book are on Vatican II and John Paul II. It was because Novak recognized the conserving features of the council—“I found myself reacting more and more negatively to the large factions of the ‘progressives’ who failed to grasp the truly conservative force of Vatican II”—far earlier than most of the powerful figures in and around the Church that he was able to see the follies of progressives elsewhere. Along with George Weigel and others, Novak saw early on the powerful impact that Blessed John Paul II would have, not only on the Church but on the Cold War and many other aspects of Western culture.

One cannot be a Catholic of Michael Novak’s gravitas and sensibilities and not be a force for good. I find his intellectual memoir to be inspiring in that sense, as well as for throwing light on the difficulties faced by the unnamed generation that is also mine (those of us born between 1933 and 1945). The parts devoted to politics as politics are not as interesting, but that may be because Novak is not very interested in power for its own sake. His love of sports doesn’t show through here enough; whoever loves American sports can hardly be a true progressive (or even a neocon). Michael Novak comes across as a kind man, a quality I was able to observe on the several occasions on which I was in his presence. A man of God, a patriot, a family man, a man who insists on hearing out his opponents as well as his friends—that’s conservative enough for me.

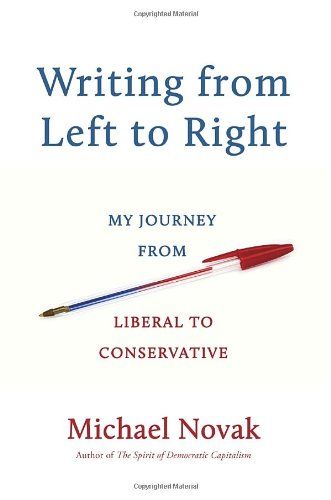

[Writing From Left to Right: My Journey From Liberal to Conservative, by Michael Novak (New York: Image) 316 pp., $24.00]

Leave a Reply