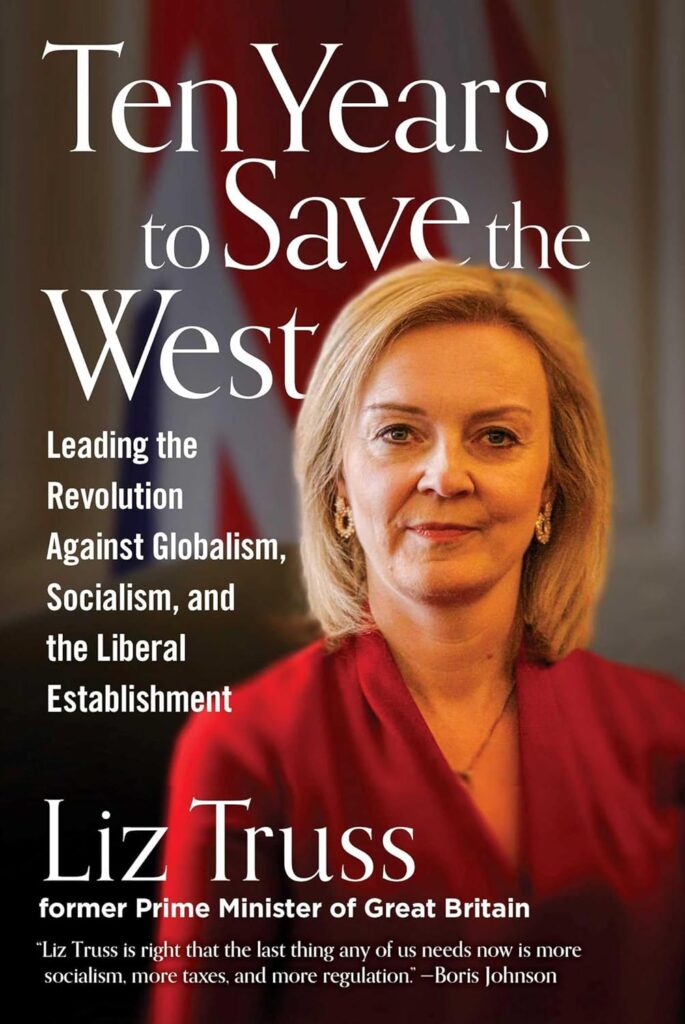

Ten Years to Save the West:

Lessons from the Only Conservative in the Room

by Liz Truss

Regnery

320 pp., $32.99

In the late 1990s, I was a member of the Conservative Party in the London inner-city suburb of Deptford—a no-hope area for Conservatives, which was possibly one of the reasons I joined.

The chairman of the local Conservative Association was a bright and energetic twentysomething blonde from Leeds who was working as an accountant for Shell. She had tensely alert features and a regrettable tendency to chortle about “socialism.” She had only joined the Conservatives in 1996, but was already committed to the “rubber chicken circuit” of dreadful party dinners and platitudinous speechifying. Serving the Conservative cause in such a district, for her, was partly an apprenticeship, a demonstration of dedication for Central Office talent spotters.

As a child of left-wing parents, she had marched against “Maggie.” Now she stressed “the market” as key to politics, outweighing all other considerations of culture, the environment, or national identity. I lost interest in such activities and moved away—only to be amused and impressed years later as my erstwhile associate ascended to higher spheres, first as an MP and then to increasingly senior ministerial posts. Then, in 2022, she twice stood outside 10 Downing Street, once to proudly announce her arrival as a radicalizing prime minister, and then to depart, with apparent relief, just 49 days later.

We had never been close, but it was impossible not to feel sympathy as left-wing Britain ululated in glee, with its customary blend of hyperbole, hypocrisy, mawkishness, sanctimony, and threats of violence, at her downfall. She had made mistakes but had also been unlucky—and could her government have been much worse than what we got instead?

She has used her involuntary sabbatical to produce a book which combines the self-justification expected from political memoirs with a manifesto for a more forceful brand of conservatism. She writes defiantly, “I am not prepared to leave the field until the battle is won.” But at the July general election, she was forced from that field, losing her Norfolk seat to Labour.

The badly battered Conservative Party is entering a painful period of reinvention. Although Truss is out of Parliament, there are still some within the Party who believe her brand of free market politics could be a vote-getter. Nigel Farage’s insurgent Reform Party, with whom the Conservatives may align, is likewise dominated by Thatcherite thinking. Truss’s book will undoubtedly have some impact on all these looming arguments.

Ten Years to Save the West will not win any literary awards. It is more like a policy paper than a personal memoir, and we have heard all these policies before, although from right-wing columnists rather than former prime ministers. There are many clichés, some half-baked anecdotes, and rash assumptions about readers’ background knowledge of obscure economic matters. She has spent too much time in free-market think tanks and at Atlanticist conferences. She also unleashed an unfair broadside against an eminent British barrister for having once represented a Russian oligarch, which undercuts her otherwise shrewd observations about the urgent need to reform Britain’s sclerotic legal system.

In her short tenure, Truss did some good things—most notably, defunding “trans rights” advisory bodies and stopping the legalization of gender self-ID—and tried to do others. She has reserves of sense, opposing “taking the knee” for BLM and toppling statues. Unlike left-wing female politicians who demand “equality” plus special privileges, Truss clearly really believes that men and women ought to be treated as equals. Her book may be self-justificatory, but never self-pitying.

We get interesting insights into the immovability and incompetence of officials, the biases of “experts,” and petty squabbles between ostensible allies. When she took over from Dominic Raab as Foreign Secretary, her petulant predecessor refused to move out of the official accommodation—so they had to share a fridge, in which she would find protein shakes obsessively labeled “Raab.”

We get some sense of the rigors of her leadership campaign, as well as daily life during her tumultuous tenure at Number 10. The job of prime minister is lonely and poorly resourced, with Truss even having to organize her own hairdressing. She has always had problems sleeping, and any innate insomnia was exacerbated by the night noises of that London address—the unending traffic, sirens, chanting of protestors—and the clock at Horse Guards, which chimes every quarter-hour. The prime minister’s flat was even infested with fleas.

One story from earlier in her career shows her personal stiffness. In 2017, after being demoted by Theresa May, she had to go and see the senior official responsible for ministerial appointments, Sue Gray. “To my surprise,” Truss recalls, “[Gray] took it upon herself to commiserate with me by giving me a hug, before telling me that as a result of my demotion, my salary was being cut. I didn’t welcome her unsolicited embrace—I am not a hugger—but given how delicate I was feeling, she got off lightly.”

May gets off less lightly, as Truss gloatingly describes her “stilted campaign events,” “awkward media appearances,” and indecisiveness. Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings are branded “anti-growth” and duplicitous, and blamed for damaging leaks to the press (Truss, too, was blamed for such leaks). Boris Johnson comes out best, although arraigned for lack of focus and having no plan for Brexit victory.

“Instinctive” is one of Truss’s favorite words and helps explain both her commitment and her failures. Described famously as a “human hand grenade,” she often alienates potential allies. “Even my best friends wouldn’t describe me as a great people manager,” she admits. The Financial Times described her stint as international trade secretary as “enthusiastic yet disruptive.” She describes herself as an “uber-optimist,” which is arguably at odds with the true Tory temperament, and not an optimal quality when trying to push a bracing economic package during a time of turmoil.

Nor does Truss have the traditionalist’s sense of poetic romance. As a young Liberal Democrat activist, she had called for the abolition of the monarchy. As a senior Conservative minister, she less forgivably dwells girlishly on John Lennon’s Imagine. “For a brief moment that night in Liverpool, we revelled in that message of idealism, escapism and hope,” she writes. She voted for the UK to remain in the EU, and long supported large-scale immigration for reductive economic reasons.

Truss loves Britain, but seems to see it as coolly abstract—an explicable interleaving of freedoms, laws, and values, and a national culture made up mostly of rational transactions. Her propensity for numbers-based explanations may be inherent, as her father is a respected mathematician. There is no evidence of interest in the arts, but then it is difficult to imagine her ever being relaxed enough to enjoy inutile things. On a visit to New York, she even bemoaned the time it took to get to the top of the Empire State Building for a photo-op.

Nor does she show any real interest in the countryside, despite having held that ministerial brief. She makes astute observations about the problems of net zero carbon policies, although not about the pollinator-devastating neonicotinoid pesticides she mistakenly approved. She even condemns the government’s wise decision to ban single-use plastic straws, as if this was not an obvious good. She bemoans the decline in UK dairy farming, without seeming to reflect this may be partly due to her sainted free trade, which has forced British crop prices down to unprofitable levels.

She generally fails to see free trade’s responsibility for the downfall of British industry and the sad decline of so many communities, although this was an inevitable result of favoring services over manufacturing and opening up British industry to overseas asset-strippers. She correctly condemns the anti-democratic outsourcing of national political powers to international bodies, but free trade is surely also a sort of outsourcing—an offshoring of national assets against the interests of local communities and nation-states. Her premiership was ironically brought down by global bond markets, an inevitable consequence of the internationalization of capital.

Her foreign policies place too much trust in nebulous and unexportable ideas about “freedom.” She fulminates about “failures to confront moral outrages around the world”—as if pompous post-Protestant moralism ought to be applied outside the Anglosphere, or even could be. She takes a strong line on China: “Anybody doing business with China in Western nations should be regarded as a pariah.” And she says Western nations ought to constitute an “economic NATO,” using market muscle to compel cultural change.

There is incoherence. She correctly condemns government negotiations over Brexit. “The old political maxim is to speak softly and carry a big stick,” she writes. “Between 2016 and 2019, the government was often shouting while carrying a twig.” But that charge could be leveled at her policy of giving Ukraine extravagant rhetorical and expensive logistical support, pointlessly provoking Russia while merely deferring Ukraine’s almost certain defeat. She is rightly skeptical about the efficacy or even good intentions of international organizations and advocates more strategic use of Britain’s foreign aid budget—yet has almost nothing to say about Islamism.

In the wake of the disastrous election that brought Liberal Keir Starmer to power, Truss must hope she can play some part in Conservative reconstruction. But she and other neo-Thatcherites should ask themselves whether bloodless economism is a satisfying answer to today’s more complex questions. Are strictures about fiscal responsibility really what English people want to hear in this country so unlike that of 1979—a country older, sicker, weaker, and more worried, an England that senses existential threat? This is an author who means terribly well, but her book seems unlikely to inspire real rebirth.

Leave a Reply