“The market is the best garden.”

—George Herbert

Lord Keynes’ biographer Robert Ski-delsky described Keynes’ principal rival in the 1930’s, Friedrich A. Hayek (1899-1992), as “the dominant intellectual influence of the last quarter of the twentieth century.” Hayek’s writings during the 1930’s on business cycles would eventually bring him a Nobel Prize in economics, but he is best known for The Road to Serfdom (1944) and his contributions to social, political, and legal theory. Hayek is the most famous modern representative of the “Austrian” school of economics, the tradition founded in the 1870’s by Carl Menger in Vienna and associated with Ludwig von Mises and Murray N. Rothbard.

Like Mises and Rothbard, Hayek is a major figure in the classical liberal, or libertarian revival, of the last three decades. Hayek’s influence was particularly strong in Britain, where he spent much of his academic career and where his admirers included George Orwell, Winston Churchill, and Margaret Thatcher. (He was not, contrary to Clement Attlee’s public claim, Churchill’s chief economic advisor.) Shortly after becoming leader of the opposition in 1975, Mrs. Thatcher interrupted a Conservative Party gathering where a pragmatic, “middle way” approach to economic policy was proposed. “This,” she said, holding up a copy of Hayek’s Constitution of Liberty (1960), “is what we believe,” slamming the book on the table.

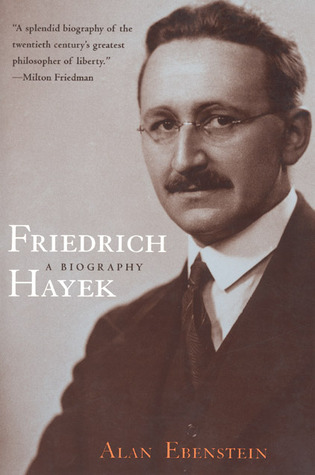

This and other anecdotes are supplied in Alan Ebenstein’s valuable biography, the first full-scale treatment of Hayek’s life and work. A vast academic literature on Hayek’s ideas and influence has emerged during the last 20 years or so, but little information has been available about his life and the genesis of his ideas (apart from a brief autobiographical fragment published in 1994 as Hayek on Hayek). Ebenstein sketches Hayek’s personal journey, intellectual development, and influence in 41 short chapters arranged chronologically, drawing largely on a set of interviews given by Hayek from 1978 to 1986, as well as Ebenstein’s own interviews of dozens of people who knew him. Unfortunately, Ebenstein’s lack of full access to Hayek’s personal papers sometimes limits the depth of his analysis.

Hayek’s life spanned the 20th century, and he made his home in some of the great intellectual centers of the period. Born Friedrich August von Hayek in 1899 to a distinguished family of Viennese intellectuals, Hayek attended the University of Vienna, earning doctorates in 1921 and 1923. Hayek was strongly influenced by Mises, who encouraged his work and set him up as director of the Austrian Institute for Business Cycle

Research. Hayek’s academic writings earned him an invitation to lecture at the London School of Economics and Political Science, where he subsequently accepted the Tooke Chair in Economics and Statistics in 1931. Hayek spent 20 years at the LSE, an institution that came to rival Cambridge in influence in economics and public policy, before transferring to the University of Chicago in 1951. After ten years with the Committee on Social Thought at Chicago, Hayek moved to Freiburg, Germany, where he mostly lived until his death in 1992. He founded the Mont Pèlerin Society, the first scholarly association for free-market intellectuals, in 1947 and was instrumental in setting up the Institute of Economic Affairs, a London-based think tank that helped drive the Thatcher revolution.

Hayek’s intellectual legacy is complex. Among mainstream economists, he is mainly known for The Road to Serfdom and his work on knowledge in the 1930’s and 40’s. Much of the knowledge necessary for running the economic system, Hayek contended, is in the form not of “scientific” or technical knowledge—the conscious awareness of the rules governing natural and social phenomena—but of “tacit” knowledge, the idiosyncratic, dispersed bits of understanding of “circumstances of time and place.” This tacit knowledge is often not consciously known even to those who possess it and can never be communicated to a central authority. Decentralized market activity, however, generates a social order that is the product “of human action but not human design” (a phrase Hayek borrowed from Adam Smith’s mentor, Adam Ferguson). This “spontaneous order” is a system that comes about through the independent actions of many individuals and produces overall benefits unintended and mostly unforeseen by those whose actions bring it about.

The “fatal conceit” of socialism, according to Hayek, is the failure to understand that this order cannot be replicated, let alone improved upon, by central direction of economic activity. From his work on the “knowledge problem,” Hayek became one of the best-known critics of socialism, though his libertarianism, like his overall social outlook, was pragmatic. He has been sharply criticized by many libertarians for tolerating a surprising degree of government intervention in the economy; some say he was not a libertarian at all, but a right-wing social demo-crat.

Hayek’s work on knowledge and competition is widely acknowledged by economists, though modern information theorists have typically disputed his conclusions. (Whither Socialism? by Joseph Stiglitz, one of the 2001 Nobel Laureates in economics, has been described as “a thinly disguised anti-Hayekian manifesto.”) Business writers such as Tom Peters, coauthor of the best-selling In Search of Excellence, have been far more enthusiastic:

My introduction to Hayek made me vow that I’d never again accede to the forces of order—the dogmatic strategic planners, the hierarchists, the central controllers who try to convince us that order and success are handmaidens.

(Hayek is the only economist included in Wired magazine’s “Encyclopedia of the New Economy,” which includes entries on information theory, knowledge management, positive feedback, and similar trendy items.)

Ebenstein’s book ably summarizes Hayek’s major contributions—a challenging task, as Hayek was (in his own characterization) a “puzzler” or “muddler” rather than a “master of his subject.” Hayek lost interest in economic theory during the 1940’s and, after moving to Chicago, began working almost exclusively on broader social and philosophical problems. As Ebenstein perceptively notes, the sustained economic growth of the postwar period was widely seen as rendering Hayek’s work on business cycles obsolete, so economists were losing interest in him as well. Ebenstein does not think much of Hayek as a technical economist, and his treatment of his major economic works is uneven. (He describes Hayek as a “philosophical economist.”) Surprisingly, the dominant economist in Ebenstein’s story is not Hayek but Milton Friedman, another important libertarian and the foremost representative of the “Chicago School.” Friedman and his Chicago colleagues have no use for the Austrian School’s theory of capital, on which the Mises-Hayek theory of the business cycle is based, or for the general Austrian approach to economics. Ebenstein relies heavily on Friedman, quoting him repeatedly and at length on Hayek’s alleged technical and methodological errors. He seems unaware that Friedman’s own “monetarist” approach to macroeconomics ceased to be influential among professional economists at least a generation ago (Hayek’s theory continues to generate interest), though Friedman remains important as a popularizer of libertarian ideas. Readers who are not followers of Friedman will be disappointed by Ebenstein’s treatment of Hayek’s economics.

Ebenstein is more careful when he turns to Hayek’s writings on social, political, and legal theory. His discussions of Hayek’s major works in social philosophy—The Constitution of Liberty (1960), Law, Legislation, and Liberty (1973-79), and The Fatal Conceit (1988)—are particularly insightful. Hayek placed enormous importance on the rule of law, where law is interpreted as “just rules of conduct,” akin to customs and morals, rather than the legal positivist conception of law as legislation, the will of the sovereign. His later work emphasized the evolutionary character of these rules (working through group, not individual, selection). Clearly, Ebenstein regards these works as Hayek’s most important intellectual contributions. Unfortunately, he does not show that Hayek’s work in these areas has had much influence on mainstream political scientists, political philosophers, or legal theorists.

Still, Alan Ebenstein has performed a valuable service by helping to put Hayek’s contributions in their intellectual and historical context, as well as by making these important ideas more accessible. As Hayek’s influence continues to grow, this book will become increasingly useful to those seeking to understand him.

[Friedrich Hayek: A Biography, by Alan Ebenstein (New York: Palgrave) 403 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply