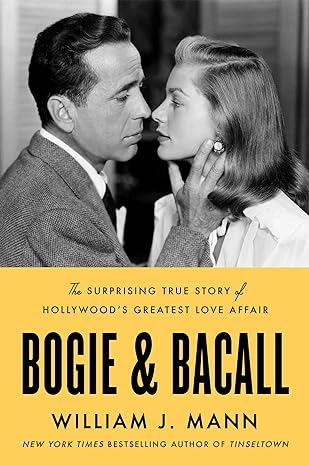

Bogie & Bacall: The Surprising True Story of Hollywood’s Greatest Love Affair

by William J. Mann

HarperCollins

656 pp., $32.00

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall epitomized Hollywood glamor. As with most of Hollywood legends, there was always a difference between the projected image (on the silver screen, literally, and figuratively, in daily life) and the reality of lives and relationships. In this book, William J. Mann explores the dichotomy between the image of a perfect Hollywood couple and the dark reality of one of the most famous marriages in Hollywood.

They were an unlikely pair. Bogart was 25 years older than Bacall, and their personalities were quite different. Bogart had been married three times before, and all three marriages had been mired in anger and alcoholism. Those traits would remain constant, but Bacall had a knack for handling Bogart unlike any other woman in his life. They were a good match.

Mann focuses on their relationship but not without first delving into the separate lives of the two stars. It is surprising to learn that before he became “Bogie,” Bogart was a shy child who received absolutely no love from his mother. She was “cold, judgmental, withholding, and emasculating,” Mann writes. Bogart’s father had the better personality and tried to develop a close relationship with his son, whatever his own weaknesses—namely, an addiction to morphine—which rendered him a neglectful parent.

Bogart was aimless, moving from one school to the next, one job to the next. Depression and anger were building up even in youth, and would become debilitating at times in adulthood, despite the fact that he achieved incredible fame as an actor. He found himself to be weak, not at all like the image of his on-screen characters, who flouted the rules of society with at least the appearance of intense masculinity. While the depression and anger remained, the aimlessness finally reached an end when young Humphrey started working for a theater company. Acting gave him a mission and a purpose, which would continue into his Hollywood years.

Bacall grew up very differently compared with Bogart’s WASP upbringing. Growing up Jewish in Brooklyn presented its own challenges, yet Betty Joan Perske was driven to transcend them. Hollywood demanded actors change their image and often their names in order to further their careers. Perske may have felt some conflict about remaking herself into Lauren Bacall, but having an opportunity to make it big in Hollywood outweighed any concern for her ethnic or familial identity.

Just as Humphrey Bogart became “Bogie,” Bacall too fully embraced change. Mann writes that Bacall’s “voice was the biggest problem.” We may recognize Bacall through the husky, mesmerizing tone of her voice, but her original voice was apparently high-pitched and fast-paced. Bacall was a “little girl with gabardine skirt and sweater,” and a “little high voice,” the director Howard Hawks recalled. Hawks had no qualms about telling Bacall this, and instead of getting offended, Bacall asked Hawks what she could do to change her voice. Hawks suggested she learn to speak from her diaphragm. Alone in her hotel room, Bacall practiced and practiced. “About a week later, she returned to Hawks’ office …. She spoke deeper and lower, at a languid pace, most (but not all) of the New York tempo smoothed out,” Mann writes.

Her metamorphosis would pay off. Bacall landed a starring role opposite Bogart in Hawks’ To Have and Have Not (1944). There already may have been sparks of romance between the pair then but, according to Mann, it was more a silver-screen suggestion than reality.

Things did sizzle on the screen, and it was mostly because of Bacall’s sexy “insolence” and that deep, husky voice. It was here that she directed some of her most famous movie lines at Bogart, which could be seen as the beginning of their real relationship. In one scene, Bacall turns before leaving the room and directs an intense parting line to Bogart’s character:

You know you don’t have to act with me. You don’t have to say anything, and you don’t have to do anything. Not a thing. Oh, maybe just whistle. You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and blow.

It was clear that Bogart and Bacall were great together. Bogart was still married, yet there was a romance with Bacall in the making. They didn’t fall wildly in love, yet they could not let go of each other.

Mann delves into the usual and inevitable characteristics of their “May-December” relationship. Was Bacall looking for a father figure, given the fact that her own father abandoned her family? Perhaps. Was Bogart looking to take care of someone, or was he just an older man finding a younger woman impossible to resist?

Bogart and Bacall quickly became the talk of Tinseltown. They were, as the phrase goes, “America’s Sweethearts,” but their life together was troubled by three strangely destructive elements.

First, Bogart’s alcoholism continued, despite the seeming happiness he found with Bacall. “In the 1940s, actors didn’t go into rehab,” Mann writes. Friends and colleagues didn’t perform interventions …no one in Bogie’s life seemed to consider that he needed help. Few saw his drinking as a problem.” This is not surprising; alcoholism abounded in those days. Yet, according to Mann, Bacall knew how to handle Bogart’s addiction. Bogart’s self-destructive alcoholism created an intense entanglement with Bacall that was a strange sort of romance.

Bacall’s obsession with Bogart involved always keeping him close, which spilled over into their parenting. Bogart didn’t appear to be capable of closeness with his children and Bacall was a distant mother. When the time came to shoot John Huston’s The African Queen (1951) in the Congo, Bacall had no problem leaving with Bogart on a shoot which ended up being six months long. Their firstborn son, Stephen, almost died in the care of a nursemaid but that didn’t stop Bacall from staying in Africa.

Bacall’s political persuasions added another component to her volatile and paradoxically, loving, relationship with Bogart. He was always publicly apolitical, whether because he wanted to keep his politics to himself or he simply didn’t care for it. But that changed with Bacall. She was very much a liberal Democrat and made no secret about it. When the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began naming people in Hollywood with Communist sympathies, Bacall was vocal in her opposition.

Raising First Amendment objections to Joseph McCarthy’s crusade is one thing, but it’s quite another to support Communist regimes. Mann does not acknowledge it in his book, but HUAC’s concern about Communist activities did not originate in fantasy. There was indeed a threat within America, even though the tactics McCarthy and others used were questionable.

There is a pervasive clichéd way of speaking about this part of American history among historians and biographers. This view fully accepts the leftist reading of history, granting lenience to the Communists, and going after HUAC’s “rabid conservatives,” as if there were no “rabid leftists.” Mann doesn’t engage too much in politics in this book, but it’s clear that he takes the side of Bacall and Bogart on HUAC. This diminishes the power of Mann’s writing because it reveals a bias.

Naturally, the fact that Bacall and Bogart were against the hearings led others to think that they were Communists themselves. Bogart seemed more annoyed than Bacall at being put in the same box as the Communists. “On a stopover in Chicago during the train ride to Los Angeles, the Bogarts held a news conference,” Mann writes. “A somber Bogie read a prepared statement … ‘I am not a Communist, I am not a Communist sympathizer. I detest Communism just as any other decent American does.’”

Although Mann does state that Bogart waffled between the left and the right most of his life, he does not analyze Bogart’s political views or provide clear explanation for his vacillation. It is true that a biographer cannot know his or her subject fully, but Bogart’s political uncertainty would have been a good starting point to delve deeper into his character. Judging from Bogart’s personality, which includes his on-screen portrayal of dark masculinity however unreal it may have been, he didn’t want to have much to do with politics at all. Was it then Bacall who inserted her political leftism into their marriage? Mann doesn’t answer that question.

Mann’s exploration of Bacall’s romantic obsession with Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson could have provided a positive answer to that question. Bacall herself admitted that she was besotted with Stevenson. As she fully inserted herself into Stevenson’s campaign, she became more and more emotionally attached to him. Although, there is no evidence of a consummation of this affair, it’s safe to say that, according to the evidence Mann provides, Bacall had an “affair of the heart” and even considered leaving Bogart for Stevenson.

It never came to that, since Stevenson disappeared from her life after he lost two elections in a row to Eisenhower. Bogart was diagnosed with cancer and died in 1957 at age 57. As he was dying, Bacall never left his side. Somehow she was still devoted to him, despite all his struggles with anger, drinking, and depression.

Though Mann reveals many aspects of both people, it is ultimately Bogart’s personality that comes through most strongly. To be sure, Bacall was a headstrong woman, but she seemed to feed off Bogart’s intensity. Would she have become the star that she was if were not for her marriage to Bogart? Maybe it’s pointless to ask, but Mann’s exploration of this paradoxical relationship reveals and confirms Bogart’s many sides. He was kind and yet volatile with a past that was both a blessing and a curse. During his era, he was a man who embodied the American consciousness.

Leave a Reply