The Extinction of Experience: Being Human in a Disembodied World

by Christine Rosen

W. W. Norton & Company

272 pp., $29.99

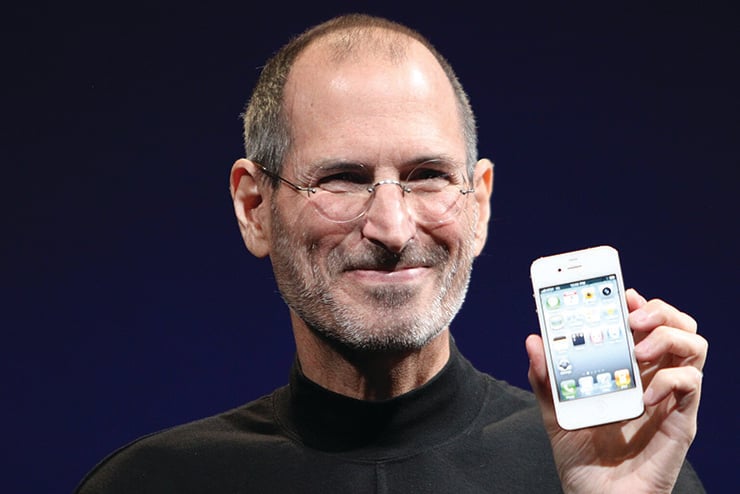

The last major revolution exploded on Jan. 9, 2007. Like all good revolutionaries, the brain trust behind this one announced its intention to “reinvent” the status quo, or go bankrupt trying. It promised a “phenomenal” and “awesome” change. The revolution would not just seize the zeitgeist but also bring mankind to its long-awaited, “truly remarkable” utopia, which every previous revolutionary had failed to deliver. “So after today,” Steve “Nostradamus” Jobs predicted, “we are not going to look at these phones quite the same way again.” Robespierre, Trotsky, and Guevara are all now drooling with jealousy down in hell. Jobs’ handheld device succeeded where Maximilien’s efficient guillotine, Leon’s wacky theory, and Che’s M1 Carbine came up short.

But this wasn’t Jobs’ first revolutionary success. He bragged on that epochal January day that he had already “changed everything” in 2001 before promising the enraptured horde, “We are going to do it again.” You were probably too busy that afternoon working, reading, or just daydreaming—three activities the revolution has snuffed out—to heed Jobs’ call to change the course of history. Today, nearly two decades later, we can survey the devastated horizon. Steve Jobs’ revolutionary iPhone has transformed human beings into lab rats who spend all their waking hours pawing the reward lever of their new handheld cage. The human species is worse off thanks to the catastrophic parting gift Steve Jobs left us before his untimely death in 2011.

Was that hyperbolic? Consider these examples. Your dinner companion has to step away from the table mid-conversation for a supposed emergency. Consumed with concern, you offer to help. When she returns, you learn that her precious child Devynn had just sent 11 texts in quick succession. Devynn’s inconsolable distress arose after the babysitter wouldn’t let Mommy’s little princess have two scoops of ice cream instead of just one as originally agreed. Your stunted conversation resumes, but no one remembers what you were talking about. Not convinced? OK, say you’re overwhelmed with sadness because you just had to put down your elderly dog. You both confess and plead to your closest friend, who’s enthralled by an Instagram video, “I haven’t been this upset since my grandmother died. How do I get over this?” After a long pause, your preoccupied friend looks up and says, “Oh, hey, how’s Fido doing?” You walk away even sadder. Still not sold? How about the three automata in the New York subway who filmed a burning woman set on fire by an illegal alien instead of trying to put out the flames?

The mountains of evidence are in; I’m just announcing the ineluctable verdict. My fellow juror, American Enterprise Institute senior fellow Christine Rosen, has also voted to convict.

Rosen reminds us that recent “technological change … has not ushered in either greater social stability or moral evolution” in The Extinction of Experience: Being Human in a Disembodied World, her must-read assessment of Jobs’ catastrophic legacy. And this reviewer appreciates her hyperbole. The wizards behind the technological curtain aren’t guiding us along the Yellow Brick Road. Instead, they have managed “to bring out the worst of human nature,” just like we saw in the subway. Rosen correctly identifies Hobbes as social media’s guiding spirit. But in his defense, not even the dismal Hobbes could have imagined anything as solitary, nasty, or brutish as TikTok, Facebook, or Twitter. Again, we have the charred human remains to prove it.

Rosen explains our descent into this Stygian inhumanity as a toxic side effect of our “collective complacence in assuming that change brings improvement.” Better to make a video of human suffering than to alleviate it. My students mock my 8-year-old iPhone. Then they happily squander an entire weekend buying a new device and transferring their silly apps onto it. The Stoic philosopher Seneca taught us that life isn’t short; it’s just that we waste so much of it.

Rosen’s proves Seneca’s point when she writes, “We now spend as much time consuming the experiences of others as we do having experiences of our own,” an insight that will fall on the deafest of ears unless someone posts it on YouTube. Our bovine acquiescence to technological change looks poised to grow as the utopian promises of AI further degrade our internet-infected conscience.

As depersonalizing masks reminded us during the pandemic, “Facial expression is our primal language.” But screens have now replaced faces as the primary focus of our gaze. Rosen tells us what we sacrifice in the trade. When we lose our primal language, we lose our humanity. And when we use screens to mediate our communication, we surrender “our ability to assess the trustworthiness of others.”

Or to paraphrase a modern American philosopher, The Notorious B.I.G., “Mo’ screens, mo’ problems.” “Civil disengagement” occurs when we glue our noses to our screens and ignore others within physical proximity, some of whom are literally on fire. As Rosen sees it, this lack of awareness has destroyed “our sense of duty to others.” She backs up that painful truth with a story about how passersby ignored an attack on a blind man in Philadelphia. No one even called 911. The civil disengagement tumor will metastasize into Stage IV civil collapse if not treated. And even if we excise the tumor early enough, Rosen warns, “Technologies work against intervention” as we calculate how many up votes our video of a violent crime might earn.

Technology has destroyed the all-important tactile aspect of learning by replacing it with screens. Why learn to write with a pencil and paper when keyboards abound? Your local school board already answered that question, and you won’t like the answer. Handwriting used to offer “a glimpse of individuality.” Those of a certain age can associate friends and relatives with their individual penmanship. Not so with keystrokes. The Common Core State Standards for Education obeyed Jobs’ revolutionary dictates and abolished cursive writing requirements. But if you can’t write it, you can’t read it, as Rosen points out.

And it gets worse. Without handwriting, our cognitive skills decline and we lose the “sensory experience of ink and paper.” Ultimately, we “lose the ability to read the words of the dead,” as any archival researcher can attest. Students who take notes by hand absorb more than those who do so on a device, since writing’s slower pace forces us to synthesize information for efficiency. In China, where 4 percent of students are “already living without handwriting,” the phrase “Take pen, forget character” presages our illiterate future. Rosen is more blunt: “A child who has mastered the keyboard but grows into an adult who still struggles to sign his own name is not an example of progress.”

Screens have even changed the simple chore of waiting. Instead of calmly waiting in line at the bank, lost in our thoughts while the ATM’s touchscreen befuddles a legally blind octogenarian, we now lose our minds if we can’t access Wi-Fi. Who has time to go to a store when you can just click “Same-Day Delivery” at Amazon? The “relentless acceleration of everyday life” has made us hopelessly impatient. Rosen cites the example of road rage here. “The often deadly overreaction to perceived slights” on the highway speaks of our impatience with our fellow citizens who are just as “flawed, tired, and distracted as we are.” And don’t forget, your video of a road rage incident might even go viral!

Thankfully, Rosen includes a counterrevolutionary manifesto in her cri de coeur. She dismisses trite suggestions that we “take a digital Sabbath, avoid multitasking, and put those phones away at the dinner table!” Instead, she goes full root and branch in her radical prescription. She cites three crucial questions the Amish ask of all emerging technologies: “How will this impact our community? Is it good for families? Does it support or undermine our values?”

While you and I and Rosen probably agree with that line of inquiry, remember that many Americans do not. Their definition of “community,” whether by race, sexual orientation, immigration status, or other polarizing quality, drives us further from any understanding of the common good that every community aspires to. Would “families” include throuples, consanguineous marriages, and same-sex pairings? And today’s reigning “values” run the gamut from prudent frugality to excess consumption, and from flag burning to flag worship. The Amish have their priors, and a long record of success to prove their inherent value. American society can’t begin to answer those questions without first finding some—any—common ground. But readers like us should take up Rosen’s suggestion with (counter)revolutionary fervor.

Holding the tech companies responsible for this mess, as Rosen also proposes, fails on several counts. Ragtag “Moms Against Technology” groups stand no chance against white shoe law firms the tech companies keep on retainer. Besides, how will those moms have time to organize when Devynn demands 24/7 real-time communication via text, voice, and emoji as she navigates her way from her therapist’s office back to her bedroom for a few hours of doomscrolling? Lobbyists will bribe politicians to ensure meaningful legislation never passes. Political scientists harp on the collective action problem as an impediment to political change. Devices have now converted that impediment into an insuperable barrier.

Let’s just put down our phones. Let’s stop aping the Addiction Industry’s BS excuse that we are powerlessly enthralled by our electronic devices or that we have a disease that forces us to pick up our phone every two minutes. Put down your phone. Turn off your iPad. Pet your dog. Take a walk. Greet a stranger. Write a letter. Curse Steve Jobs. Be a human. But first, read The Extinction of Experience.

Leave a Reply