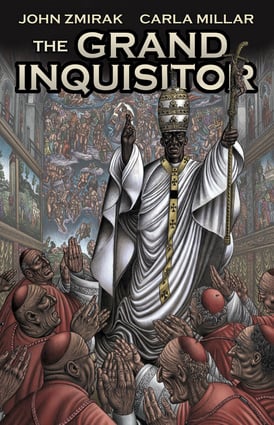

Before Vatican II, the Roman Catholic Church appeared to be a fortress against the raging tide of modernity, a supremely self-confident institution that attracted converts of the caliber of Evelyn Waugh, G.K. Chesterton, Ronald Knox, and Christopher Dawson. After Vatican II, the Church’s attitude toward modernity changed, vocations dried up, and entire countries came close to losing the Faith. Clearly, something had gone wrong. In the famous words of Pope Paul VI, the smoke of Satan had entered the sanctuary of the Church. How this happened is the subject of John Zmirak’s graphic novel The Grand Inquisitor, which tells its tale through Zmirak’s blank verse and the arresting illustrations of Canadian artist Carla Millar.

Zmirak’s novel—well written, inventive, at times even profound—deals with an issue of importance to non-Catholics, as well as Catholics. Despite the efforts of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, many established Catholic institutions in the West now seem to believe in nothing more than liberalism; the resulting loss of faith in Europe has had serious spiritual and secular consequences. I doubt, for example, that men filled with the faith of Charles Martel, Jan Sobieski, or Don John of Austria would have allowed Europe to be overrun by a quiet Islamic invasion such as the one we have witnessed in the past few decades.

The heroes of Zmirak’s novel are an African cleric famous for leading his people to martyrdom by the Islamic despots of the Sudan, who shrank from killing such willing martyrs under the cameras of CNN, and Cardinal Miroslavsky, a Ukrainian cleric who survived the Gulag. His villain is a wily veteran of Vatican II, Primo Dangeli, a priest-psychiatrist who also wears the robes of a cardinal and is drawn by Millar to resemble Teilhard de Chardin. Despite their antagonism, Miroslavsky and Dangeli see the contemporary Church in similar terms. The Ukrainian cardinal represents “Catholic tradition, in its last flowering, on the verge of final extinction,” a tradition he describes as

a vast and complex history, an elaboration of doctrine, of meditation upon the divine truths revealed by God to man, a meticulous intellectual and spiritual discipline that has been tested in the blast furnace of a hundred major heresies and encyclopedias of slander, undergone centuries of persecution, fire, sword, torture, seduction, famine, plunder, jihad, revolution, and unremitting attack by the principalities and powers of deepest Hell.

His antagonist represents “the national hierarchies . . . religious orders . . . schools and universities . . . journals and seminaries” marked by “defiance . . . mockery [and] tireless resistance to [the Pope’s] will,” men who “reckoned dead these thirty years” such “obsolete theological terms” as “Deposit of Faith,” “the Kingship of Christ,” “the contempt of this world,” and “heresy.” But the Catholic tradition represented by Miroslavsky, although weakened, is not dead, which is why it continues to arouse such fierce opposition both outside and even within the Church. Zmirak’s novel presents an ingenious explanation for how this weakening of the Faith came about, and an equally ingenious hope for recovering the former vitality of the Church Militant.

[The Grand Inquisitor, by John Zmirak and Carla Millar (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company) 76 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply