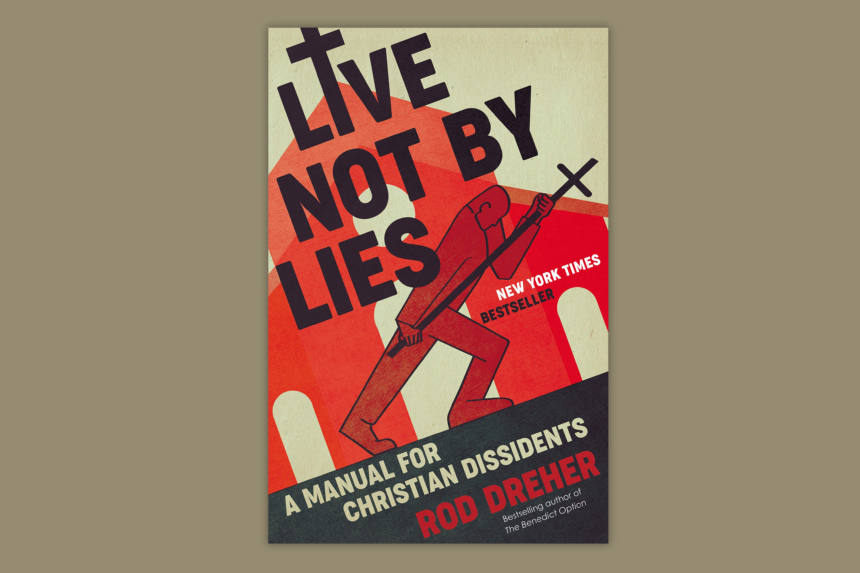

Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents

by Rod Dreher

Sentinel-Penguin Books

256 pp., $14.69

Rod Dreher is not the first to argue that America, and much of the West, has undergone a radical transformation in the post-World War II era. More specifically, we are moving at an ever-accelerating pace toward “soft totalitarianism,” he argues in this, his most recent book.

Dreher’s latest work has a twofold purpose: to provide an analysis of this new totalitarianism; and direct to conservative traditionalists, especially Christians, on how they can remain true to the faith in the coming times of “soft” persecution. Dreher encapsulates these trends by direct analogy to the experience of totalitarianism in the Soviet bloc during the 20th century.

It would be a serious mistake to dismiss the possibility of totalitarian developments in the West, Dreher argues. We are inclined to imagine that nothing of the kind could happen here, but as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn reminds us: “Alas, all the evil of the twentieth century is possible everywhere on earth.”

There are a variety of reasons for this delusional Western disposition. Above all, such claims are in direct contrast to the entire weight of liberal ideology by which the West has defined—and lavished praise upon— itself. The rhetoric of freedom from governmental control over the individual continues to be the lingua franca of the majority in our mutlticultural society, even as we have become increasingly dependent upon state and corporate power.

A second reason pertains to our inclination to see things in primarily material terms. There is a major disconnect between the West’s assumption that totalitarian nations are sloughs of poverty and deprivation, and the narratives of abundance and innovation that regale us daily in Western media and in advertising.

This disconnect emerged from the Cold War era, when the tenets of liberal democracy were pitted against socialism as a contest of standards of living and efficiency. The disastrous economic experiments of the Soviets and their satellites demonstrated the material suffering produced by totalitarian regimes. The West has, except for brief interludes, never seen the economic devastation associated with these systems; hence it is often assumed that totalitarianism is an exaggerated description of the present threat.

Our totalitarian drift is mostly well hidden, veiled by improvements in leisure, entertainment, and living standards; concealed behind rhetorical niceties and commitments to ill-defined aims such as inclusivity, tolerance, and open-mindedness. Our totalitarianism is “soft” because it is enforced and spread by ideological conformity, economic pressures, political correctness, and peer pressure rather than brute force. But it is no less destructive to our heritage and our civilizational continuity.

Dreher maintains that our soft totalitarianism is “metaphysical” in the sense that it spreads via a colonization of the mind, infecting our everyday language and behavior, in turn shaping governmental policy. It is enormously abetted by technological trends, especially those which teach us to be skilled in the arts of self-surveillance.

In light of this soft totalitarianism and its inherent demand that all social life conform with it, a pressing question arises: How then must life be lived within this reality?

If we are to effectively resist, we must understand the crucial importance of religion. A vague resistance unmoored from that bedrock is not only incapable of endurance under totalitarian conditions, but it is also at odds with the necessity to “cultivate cultural memory.” Dreher is adamant that the West is a product of the Christian religion. To cultivate cultural memory as a method of resistance demands that we rediscover, and spiritually dwell within, our Christian historical reality.

Dreher’s most fundamental exhortation is to “value nothing more than truth.” Or, in the words of Solzhenitsyn, from whom he borrowed the book’s title, “live not by lies.” Living nobly under a totalitarian regime depends on maintaining a vision of reality that refuses to betray transcendent truth in exchange for cheap approval from the defenders and reinforcers of the fraudulent social order.

Solzhenitsyn argued repeatedly that “totalitarianism is an ideology made of lies.” Whether enforced through the barrel of a gun, or through the credit system or social media, all its forms ultimately rest on compliance with a socially constructed ideology; that is, conformity to the falsehoods by which the regime exercises its hegemony.

Dreher offers the intriguing reflections of Václav Havel, in his 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless,” as an example. There, Havel, who would later become the Czech president, recalls the Soviet grocers who put out signs declaring “Workers of the world, unite!” without actually assenting to this slogan. The intention was not to announce that the grocers had, after careful consideration, determined that the workers of the world ought to unite against the exploitative capitalist class. Their purpose was to signal ideological conformity, so as to be left alone.

above: a Soviet propaganda poster reads “Workers of all countries, unite!” marking International Workers’ Day (1917-1921, public domain)

Dreher comments that “the greengrocers’ act not only confirms that this is what is expected of one in a Communist society but also perpetuates the belief that this is what it means to be a good citizen.” Or, in Havel’s words, putting out the sign reminds others what they also must do “if they don’t want to be excluded, to fall into isolation, alienate themselves from society, break the rules of the game, and risk the loss of their peace and tranquility and security.”

This reflection exposes similarities between our system and the Communist one. Do we not have our own slogans, our own culturally-defining themes that must never be called into question? Do we not display our own signs? If we sport “Black Lives Matter” insignia or fly LGBTQ flags merely out of expediency, we are announcing an ideological allegiance. If we repeat empty slogans like “diversity is our strength,” are we not falling into lockstep with the ideological assumption that racial, ethnic, and gender equality is the defining principle for which America stands? To refuse assent to the secular, egalitarian Western creed is to refuse to live by lies.

Echoing writers such as Polish philosopher Ryszard Lugutko, author of The Demon in Democracy (2016), Dreher argues that the horrors of Communist reality in the East distracted us from similar pressures toward unforgiving ideological conformity here in the West. While it is easy to see the absurdities in current LGBTQ activism narratives or accusations of “systemic” racism, these are manifestations of more fundamental presumptions that have been with us since at least the 1960s. Commitments to uncritical tolerance, “hate speech” laws, egalitarian rhetoric, inclusivity, and post-Christian secularism guide and direct the sentiments not merely of the far-left, but often of the adherents of Conservative Inc. and of mainstream, nominally religious organizations throughout the Western world.

Today’s liberalism and conservatism alike operate under a certain body of ideological commitments that has not only become its own religion, but has established itself as the standard by which all commitments are judged. Nothing exists outside this standard, and all aspects of the social order must conform to it.

It is vital to understand that what is happening in the West transcends mere governmental mechanism; our totalitarianism does not, contrary to what happened in the Soviet Union, flow primarily from the engine of state compulsion. Rather, what we are experiencing is a mobilization of all institutions within the social order. The old framework of “public vs. private” is becoming obsolete and our mental preparedness requires that we take that into account.

Recognizing that cultural survival requires more than just distinguishing between true and false propositions, Dreher identifies several themes that stand out in the experiences of the victims of Eastern totalitarianism. Among them are the importance of cultivating cultural memory, of building families as cells of resistance, of religion as a source of moral strength, of standing in solidarity with others, and of learning to see the coming suffering as a gift. On our path toward the new totalitarianism, it was the breakdown of these prerequisites for cultural survival that made the present moment possible. In addition, anti-historical presentism, secular materialism, narcissism, and the obsession with pain-avoidance all reinforce our particular crisis.

Each of the practical points in the latter part of the book focus on the testimony and example of Soviet survivors. In moving from story to story, one clearly sees an obvious difference between the strength of character of those who survived the Red Terror and the moral flaccidity of those who populate our Western mass society.

This is one reason for Dreher’s advice to see suffering as a gift. Suffering produces a certain opportunity both for personal moral refinement, and also for heroism in the face of precarious circumstances. In our mediatized age, it is the man who sees himself as “not of this world,” to use a phrase from the apostle John, who will be able to overcome it. Our age tends to debase the quality of man, and living not by lies will allow one to avoid that debasement.

That in itself is the beginning of resistance.

Leave a Reply