Octavio Paz, who was 82 when he wrote this book, asks in his preface, “Wasn’t it a little ridiculous, at the end of my days, to write a book about love?” The answer is a resounding “no.” The text is densely rich with ideas, elegant in style, and the ruminations are very wise. Paz ends the short preface noting, “The original, primordial fire, sexuality, raises the red flame of eroticism, and this in turn raises and feeds another flame, tremulous and blue; the flame of love.” His endeavor in ‘The Double Flame is one of differentiation, and amplification.

Animals always copulate in the same way, whereas humans, though copulating, transform the act into something else besides. This transformation is effected through invention, variation, the imagination. Eroticism is exclusively human, which reflects another difference between our species and other animals: an insatiable sexual thirst. We do not have periods of rut followed by sexual dormancy. We are the only living creatures without an automatic regulator (although I might suggest investigators consider the headache or prolonged television watching). The insatiability of human sexual desire has its bad as well as its good aspects, since, while it leads to procreation and to the continuation of the species and society, it is also highly subversive in its effects. “It ignores classes and hierarchies, arts and sciences, day and night. . . . It is a volcano and am one of its eruptions can bury society under a violent flow of blood.” Every society has prohibitions regulating the sexual instinct. “Without them the family would disintegrate and with it all of society. The human race, subjected to the perpetual electrical discharge of sex, has invented a lightning rod: eroticism.”

In distinguishing eroticism and love, Paz begins with the story of Eros and Psyche from Apuleius’s The Golden Ass (or Metamorphoses). Eros, a cruel divinity, falls in love with a mortal. Psyche, who returns his love. The figure of Psyche is a Platonic echo, but as Paz observes, “an unexpected transformation of Platonism.” No mere object of contemplation on some ladder that leads to the idea of love or beauty, love here becomes a love story: Eros falls in love not only with a sensual mortal, but with her soul. This story, Paz believes, anticipates the distinction between love and eroticism 1,000 years later in Provence, and it is this vision that leads to our modern view of love. He makes numerous distinctions, for example, between love as Plato understood it (“a solitary adventure”), love as the East understands it within the context of its religions, and love as it is experienced among the moderns.

For the West, at least since the advent of courtly love in Provence, the image of love can be reduced to three elements: exclusivity, or love for only one person; attraction, or one’s fate freely accepted; the person, who is a soul and a body. These elements are interrelated, interdependent, and not infrequently war among themselves. In an erotic relationship, the partner may appropriately be called an object, and the object or partner is simply interchangeable with another. Love is for one person, and this personhood is complex. In order for the attraction to be freely accepted, the loved one must be free to reciprocate. A thousand years after The Golden Ass the status of women had changed, and two of the circumstances that influenced this change were Christianity (which endowed women with a dignity unknown in paganism) and the Germanic heritage (wherein women were freer than in the Roman one).

But personhood was profoundly dependent upon the proposition that human beings have souls. When one loved a body one loved a soul, but a soul incarnated within a body. This notion of personhood derives from Greek philosophy, and from Christianity. Paz claims that our era’s rejection of the soul “has been the principal reason for the political disasters of the 20th century and of the general debasement of our civilization.” As recent science has virtually been forced to become philosophical, it has taken up the old problem of the relation of the mind to the body. Paz is optimistic about the possibilities—especially for the new science of the mind—since many of the current models are not merely mechanistic ones. But he believes that we are urgently in need of a Kant to perform a critique of scientific reason, which would allow “the dialogue between science, philosophy, and poetry [to] be the prelude to the reconstitution of the unity of culture. The prelude, as well, of the resurrection of the human person, who has been the cornerstone and wellspring of our civilization.”

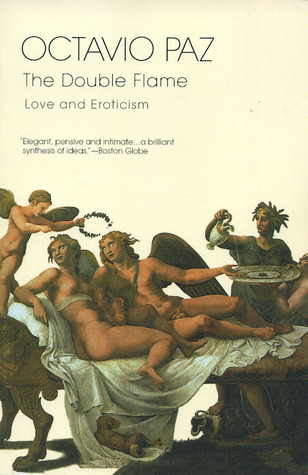

[The Double Flame: Love and Eroticism, by Octario Paz (New York: Harcourt Brace) 276 pp., $22.00]

Leave a Reply