Some acute scholar of future times, should there ever be such, will perhaps ponder over the very strange career of the United States Constitution—how it came, without changing a word, to be understood almost universally to mean things it did not mean and to be used for purposes other than, and sometimes the opposite of, what it intended.

Even its name was changed in the process. It refers to itself as “this Constitution for the United States of America” (emphasis mine)—that is, an instrument for the “common defense” and “general welfare” of those states in their joint capacity. But now we have a Constitution of rather than a Constitution for. This change of name is not unrelated to its alteration from a covenant among the governed to a grant of divine right to the rulers.

Consider this: Pundits and judges present us with the Federalist as the supreme resource for interpreting our Constitution. But that set of speculative essays has only very marginal weight as an authority. It is a partisan polemic by three men belonging to the defeated centralist party in the Philadelphia Convention. At least one of those men, Hamilton, acted in bad faith, reassuring the public that the new Constitution involved no threat of centralized power and, after it was adopted, conspiring tirelessly to twist it so as to achieve that centralized power.

The judges and pundits also call upon the debates in the Philadelphia Convention to understand the powers that the Constitution gives to government. But consider this simple truth: The Philadelphia Convention had no constitutional power whatsoever. It was a meeting of the states to prepare a draft—a draft that the people of the states could accept or reject. (Set aside that the savants of federal power go badly wrong by distorting or misunderstanding the context of that convention and often cite as binding interpretations that were discussed but actually voted down there.) Americans now believe that a group of supremely wise Founding Fathers gathered together and bestowed upon us the gift of a wonderful government. What happened to the people in this fairy tale of benevolent philosopher-kings?

The peoples of the states did eventually agree to the draft, but only after several states had stated a right to withdraw from the contract and defining alterations were promised—alterations that were capped off by that odd nullity the Tenth Amendment, which expressly limits the federal government to plainly stated specific activities which have been delegated to it by the sovereign states. Neither the convention nor the Federalist involves the people, the presumed authority in establishing this government. Madison himself got it right in one of his more lucid moments: The basis for interpreting the Constitution must lie in the proceedings of the states in ratifying, because there it received “all the validity which it possesses.” It should mean what those who established it say it means. From that standpoint, what it means is pretty clear, and the people are not replaced by some mystical wisdom of founding demigods or by the self-interested distortions concocted by lawyers and judges. In other words, the real Constitution is the one that was ratified and amended, not the one discussed by “Publius.”

Finally, this means that the sovereign people of a state are the authority on the Constitution. But that all died when Lincoln announced that the peoples of 13 states in sovereign convention assembled were merely bandits and lawbreakers to be put down by force. The true will of the people, in his assertion, was that expressed by the political party that had put him in power and which could choose for itself who were the “people.” Nationalism, a potent blend of profit-seeking and emotion, overcame constitutional government. Professor DeRosa reminds us that nationalism generally results not in the liberation of peoples but in the empowerment of rulers.

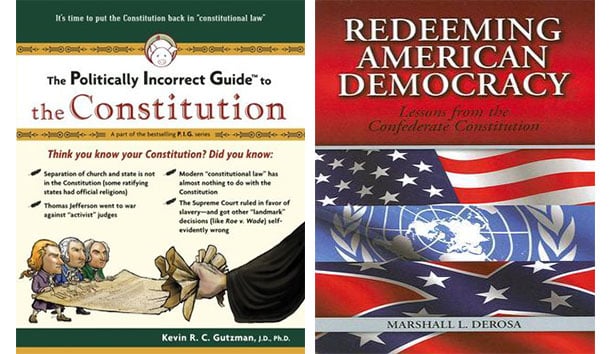

The subject could easily fill ten volumes, but all that our imagined future scholar will really need are these two books, which lay out the story as clearly and well as ever has been done or is likely to be. As Gutzman shows freshly and knowledgeably, a major part of the tale involves a long trail of blatant perversions of meaning by federal judges before and long after Lincoln. Once it was accepted that the Constitution was to be interpreted finally within a chain of case law in the special custody of judges, the game was over.

The history of the War of Southern Independence at this day is smothered in false assumptions by people who know nothing—rather, who know less than nothing, because what they know is wrong. It takes rare learning and some courage to deal with that period truthfully, as Professor DeRosa has done. The framers of the Confederate Constitution had no quarrel with the Constitution for the United States, only with the distortions that had accrued since their fathers and grandfathers had established it. The corrections that they made in the constitution for their new union offer much food for thought for our own times.

Consider this: The Confederates provided for a line-item veto of appropriations, that all laws must embody only one subject which was to be stated honestly in the title, that no “bounties” could be granted to individuals and corporations, and that federal judges and bureaucrats could be impeached by the states in which they functioned; allowed the constitution-amending process to be initiated by any three states (rather than Congress); narrowly defined the commerce clause; required a two-thirds vote of Congress to pass certain taxation and spending measures; and made a one-term president, who would thus be the constitutional statesman intended rather than a party man buying support for his reelection.

Would not such a constitution be a stronger bulwark against imperialism and more likely to redeem democracy than what we have now?

DeRosa sheds new light not only on the Confederate Constitution, but also on the jurisprudence of the 1850’s and on that of the Confederacy, which, despite its life-and-death struggle, embodied a true adherence to the “rule of law,” as the author puts it, instead of the “rule by law” under which we live. Redeeming American Democracy also exhibits how the centralizers of supranational governments and NGOs in Europe and America are now pursuing power by the same tactics of usurpations and perversions of law that destroyed “the rule of law” for the United States. Our only hope is a return to genuine constitutional government through limitations on the rulers.

Read these two learned and lucid books. I dare say you will be a better citizen for the experience.

[The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Constitution, by Kevin R.C. Gutzman (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing) 258 pp., $19.95]

[Redeeming American Democracy: Lessons From the Confederate Constitution, by Marshall L. DeRosa (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Co.) 192 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply