The second half of the life of Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) is not nearly as interesting as the first, when Russell did his major work in philosophy and mathematics and, through close contacts with the Bloomsbury Group, knew all the major writers of his time. In this second volume, Ray Monk picks his way through the trail of psychological wreckage caused by both Russell’s fear of madness and his colossal vanity. With scant sympathy, Monk convincingly portrays Russell as emotionally maimed and incapable of loving, no longer dedicated to serious intellectual work, and “astonishingly out of touch with political reality.” Frequently “superficial and dishonest,” Russell lapsed into “empty rhetoric and blind dogmatism,” dismissing rather than countering the arguments of his opponents. In this fascinating book, one of the great minds of the century is shown to have been a windbag and a bore.

Monk, author of a brilliant life of Wittgenstein (who destroyed the foundations of Russell’s work), has a penetrating intelligence and vigorous narrative style. He has mastered the enormous amount of archival material and expertly exposes the weaknesses in Russell’s fallacious arguments. (He misses one logical flaw, however. Russell states: “A hen, when scared by a motor-car, will rush across the road in order to be at home, despite thus risking its life, and in like manner, during the Blitz, I longed to be in England”— though Russell did not rush home from America during the war.) Unfortunately, after working on Bertrand Russell for more than ten years, Monk has succumbed to the biographer’s disease, resenting the subject for eating up his own life and becoming unremittingly hostile to him.

The other flaw in this impressive and emotionally powerful biography is that Monk feels obliged to offer a tedious and sometimes harsh analysis of every minor work. Monk states that, in Power: A New Social Analysis, Russell’s “solutions are too pat to be convincing and, in place of theory, he offers, for the most part, rhetoric.” But in 1938, on the eve of war, Orwell, who had a keen eye for cant, admired the book and saw its usefulness. He wrote that Russell,

like all liberals, is better at pointing out what is desirable than at explaining how to achieve it. [But] the restatement of the obvious is [now] the first duty of intelligent men. So long as he and a few others like him are alive and out of jail, we know that the world is still sane in parts.

Russell, who saw himself as the “last survivor of a bygone age,” cunningly combined an outmoded persona with a modern view of life. His skinny body, scrawny neck, crest of white hair, thin lips, weak chin, and curved Sherlockian pipe became familiar throughout the world. In his stiff high collar and waistcoat with gold watch chain, he resembled (though he wore trousers) the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland.

His quaint appearance fascinated listeners during his frequent American lecture tours—which he hated but undertook to support his ever increasing families—and during his controversial teaching stints at Chicago, UCLA, and CCNY, where he was publicly vilified and had his appointment revoked. (Monk, a British academic, rather oddly refers to the University of Harvard and to Haverfield—instead of Haverford—College.) Russell described himself, on tour, as a “mental male prostitute” and, when asked about American newspaper interviewers, replied: “Well, they’re not quite as bad as the Japs, but that’s as much as I can say for them.” His characteristically Utopian solutions to the ills of the world were reason, progress, unselfishness, generosity, and enlightened self-interest.

In the age of Einstein, Russell was able to explain difficult technical ideas to the general reader. His intellect tempered by flippancy, his mischievous attacks on conventional morality and religion, his rebellion against authority, both human and divine, and his campaign for nuclear disarmament (overcome by enthusiasm for Che Guevara, he granted an exception for Cuba) made him—despite chronic misanthropy—a secular saint for the rebellious young, who chanted; “Thanks to Bert / We’re still unhurt.” But when a boring speaker went on too long during a peace conference, Russell loudly whispered, “Now is the time to drop the bomb.”

Monk moves effortlessly between Russell’s triumphant public and disastrous private life. Russell inherited an earldom (but not the wealth that went with it) and, when convivially inebriated, remarked: “I’m as drunk as a lord. But it doesn’t matter since I am a lord!” He also got a fellowship at Trinity College, Cambridge, gave the prestigious Reith Lectures on the BBC, was awarded the Order of Merit, and (like Mommsen, Bergson, and Churchill) won the Nobel Prize for Literature for his elegant prose.

Like Edmund Wilson, Hemingway, and Bogart, Russell had four wives: Alys, Dora, Patricia (“Peter”), and Edith. His sexual entanglements were as absurdly complicated as those in A Midsummer Night’s Dream or the novels of Iris Murdoch. While married to Russell (then impotent), Dora had a child by Griffin Barry, who also had a homosexual affair with Paul Gillard, with whom Dora was in love. At the same time, the tolerant Russell, after completing his tract Marriage and Morals, slept with his children’s governess, “Peter,” an Oxford undergraduate 40 years his junior.

After marrying Russell, the ill-tempered and suicidal Peter became jealous of his supposed affair with his old flame Colette Malleson, though he was actually sleeping with a married Norwegian woman. Peter fell in love with a homosexual Spanish mystic and hoped to consummate their passion on Good Friday, but he told her he preferred to go to Mass. While Russell and his fourth wife reared the children of his schizophrenic son, John, from whom he was estranged because of his intense hatred of John’s mother, Dora, John’s equally schizophrenic ex-wife lived with her latest lover in Wales, within walking distance of Russell’s house, but refused to have anything to do with her three little girls.

Monk bluntly maintains that Russell “destroyed the life of his son.” Though his educational theories certainly had a negative effect on John, Russell, like Othello, “loved not wisely but too well.” As Erasmus wrote in In Praise of Folly: “For these kind of Men that are so given up to the Study of Wisdom are in general most unfortunate, but chiefly in their children.” Monk dramatically ends the book, five years after Russell’s death, with the fiery self-immolation of Lucy, the youngest and brightest of John’s girls. Though Monk holds Russell responsible for this tragedy, the blame clearly rests with her insane parents, who were unable to take care of her and passed on their madness to their daughter.

Russell quarreled not only with his wives and children, but with D.H. Lawrence and T.S. Eliot, Whitehead and Wittgenstein. Eliot, whose mentally disturbed wife had once been Russell’s mistress, thought of him “as the most sadly frustrated man I know. But very highly endowed—so much more so than Whitehead who has made a better career.” Other old friends were equally disappointed with his life and character. Virginia Woolf, no stranger to madness, observed:

One does not like him. Yet he is brilliant of course; perfectly outspoken; familiar. He has not much body of character. “This luminous vigorous mind seems attached to a flimsy little car. His adventures with his wives diminish his importance.

Most perceptive of all was Russell’s old Socialist colleague, Beatrice Webb. While praising poor Bertie’s “wit and subtlety, his literary skill and personal charm,” she felt he had wasted his astonishing gifts, “made a mess of his life and knows it.” Russell’s life reveals that, despite all his intelligence, he was emotionally limited and morally obtuse.

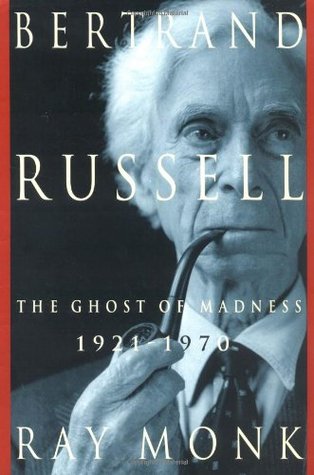

[Bertrand Russell: The Ghost of Madness, 1921-1970, by Ray Monk (New York: Free Press) 574 pp., $40.00]

Leave a Reply