To be published by a university press, one must demonstrate originality of scholarship. In a forgetful age, that is not hard to do. It is easier still when a constant rewriting of history is required to meet the ever-changing dictates of empire. This latest biography of Edgar Allan Poe promises to emphasize “as never before” his Southern identity and his work as a journalist and critic. The intention is noble; the execution, a failure.

That Poe, despite his Boston birth and long residence in several Eastern cities, was a Southerner, considered himself to be such, and was fiercely loyal to the region is no secret to any but English majors at our universities; hence, the supposed originality of the idea. Hutchisson believes he has added to our understanding of Poe’s Southernness by showing how it debased his literary criticism. Consider how Hutchisson treats the famous “Longfellow War” of 1845. He believes that Poe went after Longfellow “because of sectional bias,” the poet being a symbol of New England literary culture, which he despised. Likewise, he attributes Poe’s hostility to didacticism in poetry as springing from his fear of its “social implications,” meaning that it might undermine slavery. He even declares that Poe “resisted progressivism, because it might speed the decline of the South.”

Such charges are hardly original. They are simply another application of the dogmatic assumption that everything Southern before the war was determined by the defense of slavery. But are they true? Poe’s high opinion of Hawthorne—who was, after all, a New Englander—suggests that they are not. Poe begins his review of the Salem, Massachusetts, artist’s Twice-Told Tales (1842) with this enticing sentence: “We have always regarded the Tale (using this word in its popular acceptation) as affording the best prose opportunity for display of the highest talent.” That gives one an idea of why Poe’s critical essays were so popular, so eagerly read, and why they made his magazine publishers rich.

Poe’s hostility to Longfellow derived from a close study of his work, which he found to be indolent, imitative, and insufferably moralistic. His initial opinion was that Longfellow had talent, even genius, but shrank from “the great labor requisite for the stern demands of high art,” meaning that his poems are not finished or perfected. Then Poe discovered that Longfellow had purloined the idea behind the “Midnight Mass for the Dying Year” from Tennyson’s “The Death of the Old Year.” As a voracious reader with a powerful memory, Poe was well equipped as a literary detective. When challenged and accused of plagiarism himself, Poe fired back with a relentlessness made possible by the ammunition Longfellow had provided him, and with an earnestness derived from Poe’s recognition of his own images in the poems of a more famous and wealthy author. Compare the line—from Poe’s “To Mary” (1836), later renamed “To F—— ”—“Like some enchanted far-off isle,” with Longfellow’s first line in “Sea-Weed” (1845): “From the far off isles enchanted.”

It is curious that biographers and English professors have not taken Poe’s amply and meticulously demonstrated charges seriously. One can only attribute their failure to do so to a well-established pattern (noted by Poe) that, when artists of respectability, position, fame, and wealth steal from the unknown, the neglected, and the poor, they get away with it. Long-time readers of Chronicles are well acquainted with the examples of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Maya Angelou, whose plagiarisms have been successfully hidden by the literary and journalistic establishment.

Hutchisson believes Poe’s criticism of the New Englanders’ antislavery poems (“incendiary doggerel,” Poe called them) sprang from sectional defensiveness and a defective, because amoral, theory of art. Not so. He simply thought them bad poetry. Longfellow’s “The Slave in the Dismal Swamp” tells the story of a fleeing slave mercilessly pursued by bloodhounds into the enormous swamp sprawling across the border of Virginia and North Carolina. Poe said that it never happened. By contriving an incident, Longfellow has falsely “charge[d] his countrymen with [a] barbarity” and violated his theory that all poetry must aim at “truth.” Yet Poe included Longfellow’s poem “Waif” in his important theoretical essay, “The Poetic Principle,” commending it as an example of the highest kind of poetry, one that exalts the soul by the rhythmical creation of beauty.

Similarly, Poe considered James Russell Lowell “one of the most rabid of the Abolition fanatics,” about whom he once observed: “A fanatic of Mr. L’s species, is simply a fanatic for the sake of fanaticism, and must be a fanatic in whatever circumstances you place him.” Poe understood that there was a type of American who was ever ready to march under the banner of crusade, whatever its color or design. Nevertheless, Poe praised Lowell (“as high a poetic genius as any man in America”) and his “Legend of Brittany” “as by far the finest poetical work, of equal length, the country has produced.”

Poe thought that New England exercised a disproportionate influence on American letters, engrafting upon it a neocolonial deference toward British criticism, an elevation of moral content over excellence of form, and a disregard of writers who lived west of the Hudson River. “It is a fashion among Mr. Lowell’s set to affect a belief that there is no such thing as Southern literature,” he wrote, adding that they ignore New York writers also. But the South would not patronize its own artists and writers: “It is high time that the literary South took its own interest into its own charge.” William Gilmore Simms had the same grievance: He complained that he was not even read in his native Carolina. Jeffrey Meyers, in his biography of Poe, published in 1992, expresses no doubt that, had Poe lived, he would have sided with the Confederacy.

Hutchisson does not do justice to Poe’s critical objections to didacticism. Poe believed that “the sole legitimate object of the true poem is the creation of beauty.” Because of its “music” and suggestive power, poetry by its nature belongs among the aesthetic arts (painting, sculpture, architecture, and melody) and is not the proper medium for the inculcation of morals or the elucidation of truth, both of which require precision, terseness, perspicuity, concentration rather than expansion of mind, calm reasoning instead of passion. Didacticism degrades poetry to the sententiousness of a sermon, the censoriousness of a lecture, the temporality of a campaign slogan. If a poem contains a moral, it should be suggested only; and if a poet must wage war on vice, he should do so solely “on the ground of her deformity—her disproportion—her animosity to the fitting, to the appropriate, to the harmonious—in a word, to Beauty.” Yet Poe is not an amoral poet; his gothic tales are deeply imbued with a moral, but that moral points inward to the self-destructive and perverse propensities of the individual soul, not outward to the sins of other people, which were and are the American obsession.

Hutchisson thinks Poe’s “critical writing, as well as much of his fiction, is antidemocratic,” but he withholds specific examples of antidemocratism, offering only vague references to Poe’s elitism and Southern gentility. Hutchisson says nothing of Poe’s politics (whom he voted for, which party he favored, what he thought of the major issues of the day). Yet Poe’s book reviews and critical essays reveal a great deal, suggesting that, if he had had the time for systematic study, he could have written an enduring and valuable political treatise. Poe did reject the prevailing Jacksonian myths of his day regarding the innate wisdom and virtue of the people as sentimental bluster, which he dismisses with sparkling patrician disdain:

“One would be safe in wagering that any given public idea is erroneous, for it has yielded to the clamor of the majority.”

“There are many people in the world silly enough to be deceived by appearances.”

“The United States’ motto, E pluribus unum, may possibly have a sly allusion to Pythagoras’ definition of beauty—the reduction of many into one.”

“A valuable essay on ‘The Tyranny of Public Opinion in the United States’ [by William Kirkland] demonstrates the truth of Jefferson’s assertion, that in this country, which has set the world an example of physical liberty, the inquisition of popular sentiment overrules in practice the freedom asserted in theory by the laws.”

“The Romans worshipped their standards; and the Roman standard happened to be an eagle. Our standard is only one tenth of an Eagle—a Dollar—but we make all even by adoring it with a ten-fold devotion.”

Poe’s politics appear to have been those of a conservative Southern Whig. He scoffed at the millennial expectations and utopian dreams that were spreading out from the Transcendentalist parlors of New England and the revival tents of upstate New York. In the last year of his life, he wrote a fascinating dystopian tale, “Mellonta Tauta,” that takes place in 2848 aboard the intercontinental balloon Skylark. North America is ruled by an emperor, civil war is raging in Africa, and the plague is ravaging Europe and Asia. The narrator explains that the Americans’ ancestors once lived in an “every-man-for-himself confederacy,” known as a “Republic,” until it was discovered that, under such a government, “everybody’s business is nobody’s,” that “universal suffrage gave opportunity for fraudulent schemes” through which the most “villainous” party came to power.

Poe seems to have anticipated Clyde Wilson’s belief in historical fiction as a worthy vehicle for the transmission of historical truth. In a review of Edward Bulwer Lytton’s Rienzi: The Last of the Tribunes (1835), Poe observes: “We shall often discover in fiction the essential spirit and vitality of Historic Truth.” One thinks of the brilliant historical novels of Robert Graves, Shelby Foote, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and Gore Vidal.

I wish I could discover some genuinely new truth about Poe in this biography. The book lacks even an understanding of Poe’s significance as a cultural figure within antebellum America. For that, we must turn to Edmund Wilson’s Patriotic Gore (1962):

In the world of America just after the Revolution—loose settlements and pleasant towns on the banks of great rivers, in the span of enormous landscapes and on the edge of mysterious wilds—it was occasionally possible for the arts to take seed and quietly to flower in a purer and freer form than was possible at a later date.

Wilson points to Thoreau’s nature writings, Stephen Foster’s melodies, Melville’s novels, and Whitman’s poetry but discusses in more detail Jefferson’s architecture, Audubon’s wildlife paintings, and Poe’s tales and poems. He says that Jefferson’s educational ideal of intellectual freedom, planted at the University of Virginia, was “to realize itself in unpredictable ways”—in Poe’s original artistry and the guerrilla warfare of John Singleton Mosby.

I am reminded of a conversation between Paul Theroux and Jorge Luis Borges at the latter’s home in Buenos Aires. Among bookshelves of poetry, including Poe’s, the two men discussed The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1846), which Theroux was reading on his travels and Borges considered Poe’s “greatest book.” Borges said that there were only two American regions that mattered: New England and the South. “The South is interesting. What a pity they lost the Civil War—don’t you think it is a pity, eh?” Theroux said that Southern defeat was “inevitable.” Maybe so, replied Borges, but was “defeat so bad?” What a question!

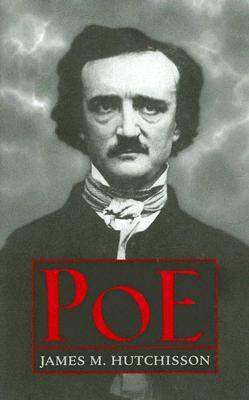

[Poe, by James M. Hutchisson (Oxford: University of Mississippi Press) 290 pp., $30.00]

Leave a Reply