“The pure products of America go crazy.”

—William Carlos Williams

The go-to-hell attitude, unique features, and deceptive talent by which we know Robert Mitchum (1917-1997) were the product of his heredity and experience. His father was a Scotch-Irish South Carolinian with some Amerindian blood—he died young in a railroad accident. His mother was Norwegian on both sides, a bohemian woman of imagination who bequeathed a love of poetry, literature, and music to her son. Mitchum’s anarchic spirit was both inherited and taught by his environment: Bridgeport, Connecticut, Delaware, and New York City, where his older sister went into show biz at an early age. As a boy, Mitchum already wrote and raised hell, and read Jack London and Jim Tully.

At 14, he left home with his mother’s blessing to discover the big world, riding the rails in Depression America, freezing and starving, scrounging and hustling, seeing men die, and winding up rather notoriously on a chain gang in Savannah, Georgia. Mitchum himself declared that everything in America that is not nailed down winds up in California, so he did, too. Marrying his childhood sweetheart and moving into a converted chicken coop, he worked with no aim in the early 1940’s, until he found his calling in the theater. Soon, he was the unshaven heavy for Hopalong Cassidy, and before the war was over, he was a rising star in Hollywood. He was on his way, and the list of movies stretches for decades. If Mitchum never took Hollywood seriously, neither did he turn his back on the money, the chance to travel the world, nor the opportunity to exercise his considerable talents.

Mitchum was no mere movie actor. He achieved, as some others have done, an iconic status—he became a god, as Parker Tyler would have it, a celluloid immortal. When he was young, the publicists formed a club of the “Mitchum Droolettes,” so great was his magnetism and their vulgarity. One bobby-soxer gushed, “He has the most immoral face I’ve ever seen!” (She meant that as praise, of course.) Mitchum more than survived the crisis of a marijuana bust and jail term in 1948—he came out of it with enhanced stature. The bad boy had to be bad, and the public liked him that way. Both the pot and the booze continued to be processed for a lifetime. Planting marijuana by his mailbox, Robert Mitchum showed an American spirit of defiance at odds with our national mythology, but not with our national character.

Robert Mitchum has today become his movies, save in the memories of family and friends. I suppose that there are two genres for which he is best remembered and America is known around the world; certain of those will remain of permanent interest. Because of the popularity of the Western when he began his career—as well as his own brawny nature—Mitchum made many Westerns. While most such films are bad, Pursued (1947) is distinctive as a noir Western—”lit by matches,” as Mitchum liked to say—and will never be forgotten. Blood on the Moon (1948) is another jewel; The Lusty Men (1952) is the best rodeo movie ever made; and Track of the Cat (1954), The Wonderful Country (1959), and El Dorado (1967) are also superior works. Mitchum never looked silly in costume, and with his voice, inflections, and body language, he put his own brand on the horse opera, forever.

In another—and not unrelated mode, Mitchum did more than make his mark. Martin Scorsese has declared, “Mitchum was film noir.” And he was, from the get-go. Don Miller has called When Strangers Marry (1944) “the finest B film ever made,” Out of the Past (1947) is an acknowledged masterpiece, thought by many to be the best noir of them all. At least three of Mitchum’s RKO movies are still regularly screened by cinephiles. Where Danger Lives (1950) is prime noir. His Kind of Woman (1951), an extravagant pre-postmodern noir experiment, remains highly appealing today. (Ironing his money, Mitchum’s character declares, “When I’m broke, I press my pants.”) Angel Face (1952) is high on the list of noirs—it was one of Jean-Luc Godard’s favorite American films. The Night of the Hunter (1955) is remarkable for many reasons. The only film directed by Charles Laughton, Hunter—which is American Gothic to the max—depends altogether on the riveting performance of Mitchum, in spite of its extravagant retro stylistics. No one who has seen Harry Powell, with L-O-V-E and H-A-T-E tattooed on his fingers, has ever forgotten this peak of Mitchumness. Cape Fear (1962) shares such a distinction: Max Cady—snide, insinuating, cunning, and as at home in dark water as an alligator—is a monster without a fright-wig in a film whose daunting ambivalence may be underestimated even today.

But having embodied the noir cycle for nearly two decades, Mitchum was more than prepared for neo-noir. The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973) showed something of his range, as if we had not suspected the extent of it already. Farewell, My Lovely (1975) is a loving goodbye to the 40’s, a superb retro-pastiche of the world that Raymond Chandler had imagined and that Mitchum, who had known Chandler, had both actually lived in and made “real” on film 30 years before. As the years went by, Mitchum was more and more an icon out of context, often wasted in dubious projects. He had a cameo in the disastrous remake of Cape Fear (1991), as Hollywood increasingly lost touch with itself. Toward the end, Mitchum appeared in a hip neo-Western called Dead Man (1995). In a way, that was fitting. He had become a totem, and looked it.

The particular reason for which I picked up Lee Server’s biography was the same that had driven me through so many other books about Robert Mitchum. I wanted to know all I could find out about Mitchum’s remarkable Thunder Road (1958), and I found Server’s treatment quite satisfactory. I wanted to understand why I had remembered that movie so well for over four decades, something in which I was hardly alone. Thunder Road remains a cult classic today. When it was released, it was a hit that recycled across the South for years— a case of Hix Don’t Nix Stix Pix—and Mitchum’s recording of “The Ballad of Thunder Road” was twice a hit on the national charts. And to know Thunder Road, you have to know Mitchum, who wrote the story, wrote the songs, produced the film and starred in it, and hired his son James to play his brother. Thunder Road has been seen as a road movie, as a hillbilly movie, as the progenitor of many trashy drive-in movies and even of—God help us—The Dukes of Hazzard. But Mitchum’s most personal film can be understood more productively in other ways.

Thunder Road is a thriller about a whiskey-runner, Luke Doolin, who is chased by the revenuers and muscled by the encroaching Mob. He oscillates between the Rillow Valley and his family and the nice girl who pursues him, and Memphis, where he delivers the goods and sees the chanteuse Francie (played by Keely Smith). His combative temperament is offset by his melancholy, because he knows he does not fit in with developments. He urges his brother to embrace a technical career, reserving the speed and the violence for himself As he says, “Someday I’ve got to fall.” The dynamite with which the goons destroy his car and his counterpart in a plot to destroy him is also the explosive that the feds use to blow up the stills. Paradoxically, the technological advancement that soups up his Fords will also render his people’s way of life obsolete. Luke is doomed. His final crash was pirated as stock footage in They Saved Hitler’s Brain (1963). Sic transit gloria mundi.

Fortified by rockabilly music, by Arthur Ripley’s location shooting, by the locals who filled the movie with authentic presence and tones, and even by endearing continuity errors and other signs of cheap production values, Thunder Road is, I think, the greatest of B movies. John Belton, writing in 1976, saw Thunder Road as a personal work keyed to “the self destructive aspects of Mitchum’s personality.” In a brief comment in the shrewdest book on Mitchum before Server’s, David Downing (1985) has grasped the structure of the film behind the thriller surface, the polarity between Rillow Valley and Memphis, between family and Francie. Seeing the film as “pervaded by melancholy,” he also sees it as an allegory of its creator’s ambivalences and frustrations: “Making movies has been Mitchum’s Thunder Road.”

The most instructive comments on Thunder Road that I have seen appear in J.W. Williamson’s striking Hillbillyland (1995). Williamson’s broad sweep helps him to view the film as the progenitor of many a Southern road movie—and not without reason. This very breadth, however, flattens out our sense of perspective, since Thunder Road towers over any other such film. Even so, Williamson understands that Thunder Road changed the view of the hillbilly as an “exotic” by treating the moonshining business from the inside—it shows the community precisely as a community, and never as eccentric or villainous. He knows, too, that “the movie . . . constructs a full-fledged tragedy and introduces a hero, Luke Doolin, who must die for his people.”

Williamson identifies two symbols, placed there by Mitchum, that allow us read the film. The first is the pennant hanging on his bedroom wall: the “battle pennon of the 52nd Regiment, 7th Army Division,” an explicit sign of Doolin’s doom. As one of his father’s peers, Jesse Penlon, says “He’s got a machine gunner’s attitude and death don’t faze him much.” Luke Doolin, alienated by experience from his community, cannot relent from his destructive and self-destructive course. The other symbol is “the ominous bird of freedom, the whippoorwill.” Keely Smith as Francie sings Mitchum’s song three times, and we are reminded that The Whippoorwill was the film’s original title. Williamson goes so far as to point out, brilliantly, that when Doolin leaps from Carl Kogan’s window onto a convenient dump truck loaded with sand, he flies like a free but doomed bird himself, one who cannot be manipulated by the music of Kogan’s tape recorder. Here we must add that “The Ballad of Thunder Road” identifies Doolin as a “whippoorwill” in its second line. We may add that, when Luke first goes to see his daddy at the still and tells him about the death of Niles Penlon, his father replies about having heard a corpse-bird.

I am dissatisfied not so much with Williamson’s treatment of Thunder Road as with his category, “hillbillies.” Neither am I comfortable with the exclusive association of Thunder Road with junk like any number of road movies about good old boys. So how should Thunder Road be classified? I have two answers that I hope will renew appreciation for this oldie-but-goodie.

The first is to place the film in the category of film noir, which may seem either an obvious or a weak suggestion—but it is not a suggestion I have seen anywhere. Thunder Road is not listed in any book on noir I know, not even in Silver and Ward’s encyclopedic account. But noir says something about Mitchum’s imagination. After all, Mitchum was one of the stalwarts of film noir; add to that the vision of night, of darkness, of the day-for-night shots in Thunder Road, as well as the familiar association with violence, automobiles, crime, cops, and—above all—doom. The rustic setting is no problem, since there is so much urban business. Carl Kogan and his hoods would be right at home in a film noir—and so is the nightclub singer, Francie. Besides, Moonrise (1949) is a noir set in the rural South.

But another category suggests itself as well, and that is the “Southern”—so I call it in parallel with “Western.” There is a lot to say about Thunder Road as a Southern movie—more than a movie set in the South, it’s a movie about the South. We have the display of Southern accents and manners, folklore and music, values and culture. Williamson has noted much (though not all) of this, in Doolin’s chivalric attitudes toward women, his respect for his parents, and solicitude for his brother. The scene in the tobacco barn, in which the men of the community discuss their options, is very effective, indeed one of the best depictions of humble democracy, of community in action, ever filmed. (Such a scene can be compared with similar ones in Shane.) The scene at church is authentic, as is the boredom of Robin Doolin and the absence of Luke.

More powerfully Southern, in a larger sense, is the evocation of dialectical opposition—social, economic, and otherwise. Because the South lagged behind in economic and social development, it has always been used as the ostensible topic or as a vehicle of dramatization, in Swallow Barn before the Civil War, and in Gone With the Wind long after. When the men discuss secession in the great opening scene of the novel and movie, Scarlett O’Hara is preoccupied with her manipulations. The contrast is effective throughout the story. Scarlett kills a Yankee, but she also, as a capitalist, becomes one. She gains wealth and loses the reason to have any. It is a universal story, not just a Southern one, though set firmly in Georgia. The dialectical vision is of two opposed economies and societies that, melded in war, create a synthesis in which the strong survive—at a cost. Marx would have understood. Hegel would have seen Scarlett as alienated not from her labor (or that of her father’s slaves) but from herself Gone With the Wind, misread to this day, shares something powerful with Thunder Road—which is known as “the Gone With the Wind of the drive-ins,” as Server has noted.

Lucas Doolin is, like Scarlett O’Hara, a partly admirable but self-destructive protagonist. He exists within community, but deep down is not part of it, as his rivals (“cousins”) and the women who love him know. Predisposed to violence and never backing down from a challenge, he has no future. The Southern background (here, the Cumberland country, Tennessee and Kentucky) is the scene of dialectical conflict because of the possibility of contrast. The bureaucratic T-men (or ATF agents, as we would say today) are as much the enemy as the urban crooks. Either way, whether through legal nicety and taxpaying, or through the illegal mob operation, the moonshining enterprise has no hope of maintaining its base, its innocence, or its liberty. Papa Doolin says otherwise: “We’ll be back in business, bright eyed and bushy tailed as ever.” But today, in fact, moonshine does not cut much mustard. Marijuana is the surreptitious cash cow in the contemporary South.

Many familiar films show a dialectical background such as I have indicated, what Andrew Lytic has called, in reference to fiction, “the enveloping action.” The sense of time passing and inevitable change haunts many a Western of quality. Indeed, the passing of the old order is the explicit topic of the most famous Westerns. Shane (1953) makes a suggestive comparison with Thunder Road. The dialectic is clear; The old cattle baron, Ryker, cannot long stand in the way of progress in the form of the homesteaders. The hired killer Wilson forces the gunfighter Shane to return to his violent ways, which he does out of love for the Starrett family. The scene in Grafton’s general store is suggestive of economic development and nostalgia as well: The homesteaders gawk at the catalogue, and Shane is shocked by the price of store-bought clothes. He regresses to his old buckskins as he discusses with Ryker the obsolescence of their respective ways of life: “The difference is, I know it.”

Thunder Road has a similar sense of social and economic conflict. Luke Doolin is a darker character, however, than Shane, who seems a paladin out of a romance. But the affinity with Shane and other such Westerns, I think, shows something of the stature of Thunder Road as more than a noir melodrama. It is a Southern-situated treatment of the ongoing crisis of modernization, which is the great topic of our consideration in the media of discourse, from Defoe to Tolstoy to Margaret Mitchell—and to Robert Mitchum, whom I have wanted to thank since 1958. Better too late than never.

I thank Lee Server as well. Robert Mitchum is not only the best book about Mitchum and his movies—it is also the best book I have ever seen about Hollywood. I think its distinctions are twofold. First, it takes us as close as possible to the personality of an enigmatic man, and shows us, past the barroom brawls and bad-boy antics, a man who was gifted, sensitive, and even sweet. Server shows us how Mitchum was impaled on the horns of a dilemma. A natural rebel, he was trapped by the need to become part of the system in order to afford his distance from it. Robert Mitchum’s sense of absurdity, earned the hard way, was bound to be stimulated to unendurable exasperation in La-La Land. Whatever Mitchum was, he was not a phony, and reading about him can be a great pleasure. He was hard to know but easy to enjoy. When George Peppard asked him if he had ever studied the Stanislavsky Method, Mitchum replied, “No, but I’ve studied the Smirnoff Method.”

The other distinction of Server’s Mitchum, I think, is its nuanced precision in defining the moment and the value of so many films. The directors and their idiosyncrasies, the cinematographers, the other actors, the exact social and political contexts of a given situation—it is all there and almost always spot on. There are a few passages where Server assumes the leftist interpretation of the anticommunist episode, but that has long been routine. Otherwise, Lee Server has excelled in rendering the personality and the career that we know from 54 years before the camera. He has shown us the Mitchum who was crazy like a fox. Defiant to the end, Mitchum was on oxygen as his lungs failed him and cancer destroyed him. Of the oxygen, he said, “I only need it to breathe.” The last thing he did was smoke an unfiltered Pall Mall—before he flew on to the only real freedom there is.

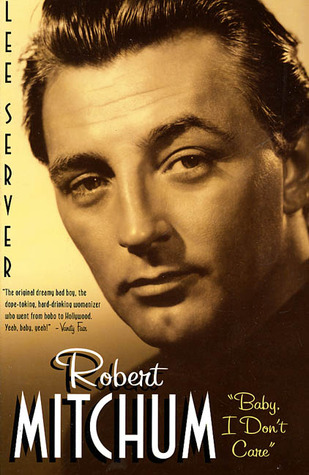

[Robert Mitchum: “Baby, I Don’t Care”, by Lee Server (New York: St. Martin’s Press) 590 pp., $32.50]

Leave a Reply