Marlowe’s back, and Parker’s got him. Well he should. Parker knows every one of Chandler’s quirks: he wrote part of his dissertation about Chandler twenty years ago. And then he started writing his Spenser books. (Where do you suppose he got the idea to name his private eye after a 16th-century English poet?) But Spenser is very East Coast—unlike Marlowe, the disillusioned voice of La-La Land.

There’s no point in belaboring the “plot” or the action of Poodle Springs—there wasn’t much point to that in Chandler’s books, either, because readers followed Marlowe for the uneasy atmosphere and the snappy patter, not for the rhinestone ratiocination or even for what was going to happen next. Readers hung not on what Marlowe said but on how he said it; they turned the pages of the books because Raymond Chandler compelled them with what he called “magic” and “music.”

Parker undoubtedly has some of that wise-cracking Marlovian magic. His ventriloquism is accomplished—he makes you want to turn the page for some more of this sort of stuff:

“Do detectives have fights, Mr. Marlowe?” she said.

“Sometimes,” I said. “Usually we put the criminal in his place with a well-polished phrase.”

“Are you carrying a gun?” I shook my head. “I didn’t know you’d be here,” I said.

Sometimes, though, Parker misfires: “I was so far out on the limb now . . . that I felt like a coconut.” That one doesn’t fly because coconuts don’t grow far out on limbs. On the whole, though, Parker maintains that certain Chandlerian strain:

For a change of pace I swiveled my chair around and stared out the window at Hollywood Boulevard for a while. The first idea I had was that it was time to change the grease in the fryolator in the coffee shop downstairs.

Now that one was bottled in bond.

So never mind about the case Marlowe works on. The point is, he’s married. Raymond Chandler himself wrote the first four chapters right before he died in 1959. Those four chapters are familiar to Chandlerians from Raymond Chandler Speaking (1962), and are here imaginatively continued by Parker, who’s done his homework. He remembers that Marlowe met Linda Loring in The Long Goodbye (1954) while they were both drinking gimlets, so we have an authentic reprise of that potent cocktail. We have pornography, as in The Big Sleep, an allusion to the gambling ships of Farewell, My Lovely, a key photograph as in The High Window, a Santa Ana as in “Red Wind,” a nostalgic reflection as in The Little Sister. This was Chandlertown in 1949:

I used to like this town. . . . A long time ago. There were trees along Wilshire Boulevard. Beverly Hills was a country town. Westwood was bare hills and lots offering at eleven hundred dollars and no takers. Hollywood was a bunch of frame houses on the interurban line. Los Angeles was just a big dry sunny place with ugly homes and no style, but goodhearted and peaceful. It had the climate they just yap about now. People used to sleep out on porches. Little groups who thought they were intellectual used to call it the Athens of America. It wasn’t that, but it wasn’t a neon-lighted slum either.

Parker’s paraphrase, in 1989, goes like this:

It was one of those comfortable cool bungalows with big front porches that they used to build at about the time that L.A. was a sprawling comfortable place with a lot of sunshine and no smog. People used to sit on those porches in the evening and sip iced tea and watch the neighbors water their lawns with long loping sweeps of a hose. They used to sleep with the front door open and the screen door held with a simple hook. They used to listen to the radio, and sometimes on Sundays they’d take one of the interurban trains out to the beach for a picnic.

The mimicry here may be a little too close for comfort.

Better is Parker’s Chapter 20, for my money his best writing in this book. There he more than imitates Chandler—he recreates him. Marlowe’s guilty foray into a sleazy saloon and his manipulative flirtation with a barfly seem to echo some of Chandler’s most powerful pages, ones in which he tangles with rummies in Farewell, My Lovely and The Lady in the Lake. Parker excels with the poetry of disgust, and uses one of Chandler’s signature words—”smeared”—showing this reader that his understanding of Chandler goes deeper than superficial imitation.

It’s all there: the knightly imagery, the gigantic house or castle remembered from the beginnings of The Big Sleep and The High Window, the flashy figures of speech like “She got some wine in. She was drinking it as if the four horsemen of the Apocalypse had been sighted in Encino.” Yet the necessary emphasis on Marlowe’s marital conflicts takes us away from strength and toward weakness. Chandler himself questioned whether Marlowe should or could ever marry—it would be “quite out of character,” he wrote in the year of his death.

And so it is. Robert Parker’s continuation of a project that Chandler himself might have abandoned if he had lived longer is a shrewd and professional one. Poodle Springs is definitely worthwhile for anyone in the market for a detective story—it’s enjoyable, entertaining, and satisfying. But it does not evade a flaw inherent in the project itself: its central action is a first-rate recreation of second-rate Chandler—the Chandler who wrote the Linda Loring passages from The Long Goodbye, Playback, and the first four chapters of Poodle Springs.

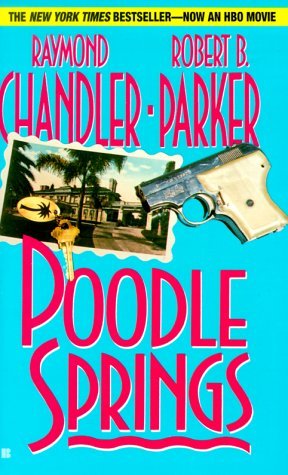

[Poodle Springs, by Raymond Chandler and Robert E. Parker (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons) 268 pp., $18.95]

Leave a Reply