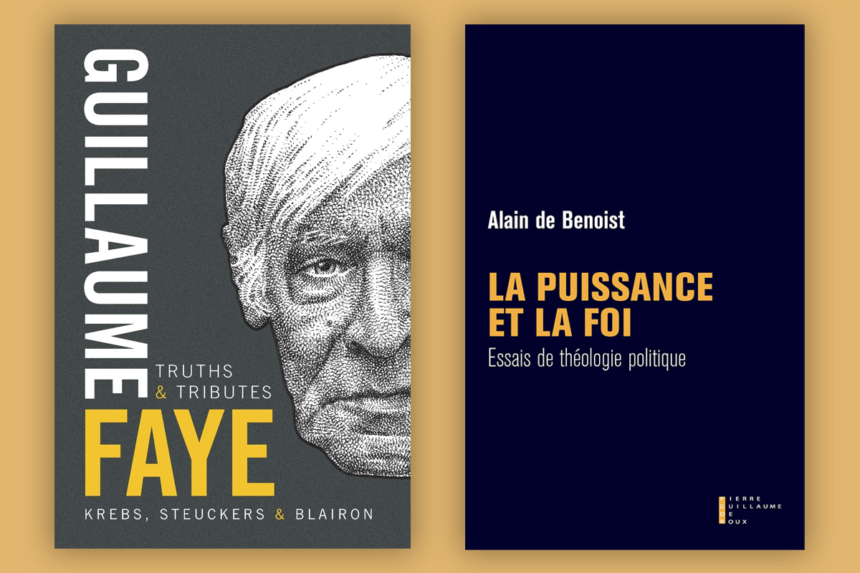

Guillaume Faye: Truths and Tributes

by Pierre Krebs, Robert Steuckers, and Pierre-Émile Blairon

Arktos Media

210 pp., $27.50

La puissance et la foi: Essais de théologie politique

by Alain de Benoist

PG de Roux

336 pp., EUR$39.00

I stumbled upon the writing of Alain de Benoist more than a quarter century ago as a graduate student. I was astounded that someone of this apparent acuity had so completely escaped my attention. Asking my Francophone associates about him, I was quickly brought up to speed.

“You must stop reading him!” one of my professors, a Frenchman, exasperatedly told me. “Why?” came my naïve response. “It’s not that he’s wrong,” my protective friend sighed. “It’s that too many people want him to be wrong desperately enough that they will punish you if they ever find out you are at all interested in him.”

Students of human psychology will know that this is the worst thing to tell someone about an object of interest if the goal is to get him to leave it alone. I have remained an avid reader of Benoist despite my well-intentioned friend’s warning. I discovered Guillaume Faye only much later, and by then I was tenured and thus even more indifferent to the reactions of nervous peers. Faye, too, struck me as someone far too important to be frightened away from by the control freaks of academia.

Benoist and Faye are two of the most formidable figures of the French Nouvelle Droite (“New Right”). This movement has labored under malicious distortions of its positions, distortions pushed vigorously by enemies both on the left and the globalist right for half a century. Faye died in 2019, and Benoist will be 78 this year. We find ourselves in a proper moment, then, to briefly consider their legacies in taking a look at the almost unimaginably productive Benoist’s latest book and a posthumous tribute to Faye.

above left: French journalist and writer Guillaume Faye (Photo by Claude Truong-Ngoc / Wikimedia Commons) above right: French philosopher Alain de Benoist (Facebook)

The publisher of Truths and Tributes, Arktos Media, has done much in recent years to make Faye more widely known to the English-speaking public. A great deal of his writing is now available in English, and the interested novice reader frankly does well to read another of Faye’s books first, leaving Truths and Tributes for later.

It is not that this small volume has nothing of interest. It is however targeted at a very specific audience, spending much time in the weeds of Nouvelle Droite’s history and its main organizational structure, GRECE, the Research and Study Group for European Civilization. It lingers especially over the story of Faye’s unceremonious ejection from GRECE.

For those without much knowledge of Faye, Pierre-Émile Blairon’s chapter, “Guillaume Faye, an Awakener of the Twenty-First Century,” provides a summary of main themes in Faye’s writing. The addenda, too, contain useful sketches of several of Faye’s most important books: Convergence of Catastrophes, The Colonisation of Europe, and Why We Fight.

They give readers a concise introduction to Faye’s analysis of a combination of threats: global pandemics and their governmental consolidation, natural disasters with their myriad consequences, and especially demographic crises caused by massive non-Western immigration and declining Western birthrates. Together, these issues have put Europe and the rest of the Western world, including the United States, in an exceedingly precarious position.

Meticulous details of Faye’s intellectual trajectory throughout his decades-long career are found in the longer essays by Robert Steuckers. These essays also spend much space narrating the political in-fighting of GRECE. Yet all the impressive detail is never totaled up to a summary view of Faye’s contribution to rightist political thought. Disappointingly, one of his most compelling books, in my reading at least, Sex and Deviance, is somehow entirely overlooked in Truths and Tributes.

Many are scandalized by Faye’s examination of Muslim immigration and France’s almost complete failure to integrate those immigrants. Yet despite some rhetorical excess in his presentation, few of those offended have ventured out into the field to empirically test Faye’s observations on the country’s transformation.

I will long remember a scene that brought this point home to me. During a sabbatical leave some years ago my family and I lived in the storied 16th arrondissement, or district, of Paris. Our apartment was in a beautiful old building in Auteuil, near the Roland Garros stadium, where the tennis gods and goddesses gather annually for the French Open, and only blocks from the building where Marcel Proust labored for years on his voluminous literary rendering of fin-de-siècle French high society. Yet, even in this posh neighborhood, the evidence of Faye’s claims about the ever-growing reach of Islam in France was palpable.

Daily, I took my daughter several metro stops to her school, taking a leisurely half hour walk back to the apartment before beginning my own workday. And daily, as I returned, I would see group after group of Muslim women in niqab facial veils leading their sons and frequently hijab-clad daughters to school. This was before the French ban on this practice, around the same time that the daily news was dominated by gangs of young street criminals of predominantly Muslim North African origin. The youths were hijacking city buses at gunpoint and setting fire to hundreds of vehicles in the north of the city, near Sacré-Coeur, not far from sites that rank among the most touristy locations in Paris. If someone had told me a decade earlier that I would shortly be seeing such sights in the middle of Paris, I would not have believed him.

The story of Faye’s progressive distancing from GRECE as given in Truths and Tributes is about both the content of ideas and the crude power politics of the group’s leaders. Faye’s provocations, especially on Islam, allegedly jeopardized GRECE efforts at respectability. Several of the volume’s writers characterize the growing division between Benoist and Faye as the former’s attention to increasingly arcane, academic debates contrasted with the latter’s laser focus on the practical political and cultural revolutions that were transforming France. But the accusation that Benoist and GRECE sought respectability in the eyes of the mainstream press and academia is hard to sustain given the nonstop hostility of the latter groups for the New Right. Of equal fragility is the claim that Benoist has never articulated serious opposition to multiculturalist immigration.

One is left disheartened that these squabbles within the most intellectually formidable French right-wing movement could not have been resolved or at least subordinated to the more essential task of the war with the left. The New Right’s civil war was between factions that each had considerable substance to offer.

Faye was the New Right’s street fighter, a political brawler whose favored philosophical arena was the speaker’s podium after a few (or many) drinks. Benoist, in contrast, has been its austere, bookish scholar, sketching out a careful position in a context of previous political theoretical work on the right in a seemingly unending sea of books and other writing. La puissance et la foi (“Power and Faith”) is a book of essays on political theology, and fully half of it is devoted to perhaps the subject’s most imposing scholar, Carl Schmitt. Benoist explores Schmitt’s textual debates with several other European thinkers—among them the French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, a friend of Schmitt’s before Maritain’s political turn to the left—on the relationship of politics, religion, and secularization.

Schmitt saw the roots of Catholic theology in purportedly secular modern political systems. Benoist deftly shows how Schmitt outmaneuvered the theologian Erik Peterson, who rejected any compatibility between the Christian view of God and the structure of a political state, by demonstrating how the effort to class theology outside politics is itself a political move. No claim of neutrality can, on this matter, hope to elude the conflict over who will get to impose his interests on whom.

The final essay in this section of the book takes a fascinating look at Schmitt’s utilization of the symbolism of earth and sea to discuss the nature of political power and the evolution of international law. Among other things, it offers insights into Schmitt’s admiration for the seafaring tales of Herman Melville. In all these Schmittian studies, Benoist takes the role of a remarkably objective exegete, interested foremost in making sense of the texts’ arguments, though clearly very partial to the elements of Schmitt’s framework.

The second half of Power and Faith consists of essays exploring the historical role of Judeo-Christian religious systems in matters of political conflict. In several of these, Benoist takes up a critical position on Christianity that he has articulated at length elsewhere, especially in a book on paganism that defends indigenous European religions as more suited to European peoples than Christianity.

In the chapter “Sacred Violence, War, and Monotheism,” Benoist lays out the biblical evidence of the Judeo-Christian tradition’s implication in the justification of war and even genocide through religious means. Monotheism seems for Benoist almost genetically linked to globalist antinationalist ambition. In the book’s final chapter, he argues that the Christian notion of original sin is an unnecessary and perhaps counterproductive understanding of human nature for a realist conservative political theory.

The question of where religion sits in the current political struggle for the survival of Europe is central for each of these thinkers. Many on the right believe Christianity is indispensable to European identity. They believe this even if only in the essentially ethnic and not necessarily personally convicted way that Montaigne intended when he wrote that “we are Christians by the same title as we are natives of Perigord or Germany.” This suggests that tensions between European identity and Islam might be expected as an eternal feature of cultural politics. Neither Faye nor Benoist accepts the proposition about the Christian core of European identity, yet both still see Islam as a considerable threat to European identity.

In addition to Nouvelle Droite’s critical thought toward Christianity, the place of America in their political analyses raises suspicions in some right-leaning American circles. Committed nationalists, Faye and Benoist are united in their hostility to the commercial imperialism that has become a dominant aspect of U.S. engagement with the rest of the world.

But Americans ought to reckon with the criticisms these Europeans make of American statecraft and culture. All that Faye and Benoist say about the threat posed to conservatives around the globe by aspects of American culture is intellectually defensible, and some of it is transparently true. The imperial exportation of the most poisonous strains of America’s popular culture is one example. The community-crushing philosophy of markets as the core of human life is another.

Pan-Europeanism is championed by both thinkers, but certainly not in the neoliberal globalist guise of the European Union. A sustainable European political order will have to be driven by recognition of two realities that appear to be in competition. Namely, the civilizational unities that bind people across the continent’s national boundaries, and the ethnic differences tied to local communities and histories that must be respected and built into any transnational relations.

In a manifesto for a European renaissance, Benoist articulated the same stances on a few key practical cultural issues that Faye took on at great length. These include the rejection of large-scale multiculturalist immigration policies and the affirmation of a view of human nature that takes the reality of the sex difference as a foundational structure in any polity.

Benoist, in introducing his magnificent View from the Right—which Arktos recently translated in three thick volumes—defined the authentic right neatly. It is, he said, the determination to view the diversity of things in the world and the inequalities among them that necessarily come from that diversity as positive things. It is also to ceaselessly oppose all efforts to homogenize and thereby equalize the diverse.

In other words, respect for real differences and war against artificial, forced homogeneity and egalitarianism defines the authentic right. All understanding of the relationship of politics and religion operates under that axiom for Benoist, and all that Faye wrote is consistent with it as well.

On this elemental note, then, the split between these two great thinkers of the Nouvelle Droite disappears and we discover to our delight a unified body of thought—one that will be useful for our own battles against the left on this side of the Atlantic.

Leave a Reply