“Poetry is the language of the state of crisis.”

—Stéphane Mallarmé

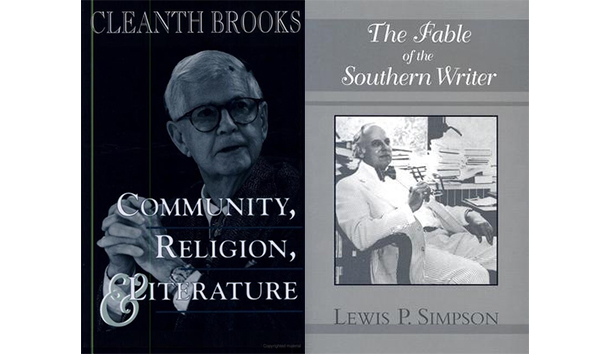

When Cleanth Brooks died at 87 in 1994, a great era of American literary criticism ended. Brooks had been one of John Crowe Ransom’s prize students at Vanderbilt, and when Ransom issued the call for a method of criticism of poetry that would not fall prey to the errors of earlier generations, Brooks and Robert Penn Warren, another of Ransom’s protégés, responded with Understanding Poetry, perhaps the most influential literary textbook ever written. Ransom, Brooks, and Warren thus became forever associated with the New Criticism, a movement which took, not very accurately, its name from Ransom’s 1941 collection of essays evaluating important recent critics (neither Brooks nor Warren was among them).

In a note to the instructor in the first edition of Understanding Poetry, Brooks sought to avoid some of the common “temptations” that resulted in study of substitutes for a poem instead of the poem itself. These included “paraphrase of logical and narrative content,” “study of biographical and historical materials,” and “inspirational and didactic interpretation.” Instead, Brooks and Warren proposed “close reading” of the poem, focusing on it as a consciously crafted aesthetic object that was more or less complete in itself. Brooks greatly admired John Donne’s “The Canonization,” and its comparison of a successful poem to a “well wrought urn” leant him the title of his best-known book. Whatever a poem was, it was certainly not to be read as a mere adjunct to personal crises in the poet’s life or as a footnote to historical events.

But over the years, as the methods of Brooks and Warren became standardized within English departments, the New Criticism established a hegemony and hardened into an orthodoxy with a dogma as rigid as that of any earlier school. One learned, from the zealous followers of Brooks and Warren, that all biographical and historical information was to be excluded from interpretation. as well as any statements made by the poet about what he or she was trying to do (the “intentional fallacy”) or any mention of how the poem succeeded in stimulating the reader’s emotional and intellectual responses (the “affective fallacy”). In its most extreme form, which came to dominate American English departments in the late 1950’s, academic New Criticism suffered from cultural and historical myopia, concentrating on the ambiguities of poetic minutiae to the exclusion of the larger contexts of life and times in which poetry is created. When the reaction against the New Criticism surfaced in the mid-1960’s, it was swift and merciless, replacing close reading with a bewildering array of critical theories which seemed to focus on almost anything but the text. To his considerable bemusement, the gentle Professor Brooks found himself and his followers demonized as a band of elitist snobs interested only in maintaining the status quo of an exclusive canon largely comprising white male authors.

It is sad that a critic as fundamentally decent as Brooks would have to end his career defending himself against such charges, but several of the essays in Community, Religion & Literature do just that. Brooks patiently explains, for what must have been the umpteenth time, that omitting biographical notes from Understanding Poetry was dictated not by a belief in the irrelevance of an author’s life but simply by considerations of space. He seems genuinely amazed that his younger colleague at Yale, Harold Bloom, could have based a whole critical method on an Oedipal “anxiety of influence.” The typical poet. Brooks notes, “is not so much concerned to slay his literary father as to commit acts of mayhem on his brother poets.” He allows J. Hillis Miller, one of the chief recent claimants to the throne of theory, to be hoist with the petard of his own ludicrous deconstruction of Wordsworth’s “A Slumber Did My Spirit Steal.” Similarly, he notes of Stanley Fish’s Is There a Text in This Class—the ur-text of contemporary reader-response theory—that the varying student responses that led Fish to conclude that literary texts are essentially indeterminate only demonstrate how in a classroom “a strong-willed and magnetic individual can engineer such changes almost to order.” The solid common sense that Brooks evidences throughout his writings will be sorely missed.

When Brooks left Louisiana State University for Yale, he also left behind the Southern Review, which he had cofounded and edited with Warren. That periodical, which provided much of the impetus for the Southern literary renaissance, languished for over 20 years before it was revived and restored to eminence in the 1960’s by Donald Stanford and Lewis P. Simpson. Simpson’s The Fable of the Southern Writer concentrates on a series of representative figures that begins with Jefferson and John Randolph and extends to Faulkner, Tate, Warren, and the overlooked Kentucky novelist Elizabeth Madox Roberts, whom he subjects to a brilliant analysis based on what he calls her “effort to transcend the constraint the modern subjectivity of history imposes on the imagination of the literary artist.” Like her contemporary Faulkner, Roberts, arriving at the universal with first steps planted in her native soil, “discovered what we are like: we believe in the idea but not in the fact; . . . in the idea of community but not in community; . . . in the idea of love but not in the act of love.”

Simpson’s criticism displays a range that is markedly different from that of Brooks. As his title indicates, he is concerned only with Southerners, and, as his methods quickly display, he prefers the role of cultural historian to that of the literary critic. Simpson is heir to the tradition established by V.L. Parrington in Main Currents in American Thought, a book that held tremendous influence in American studies when he was attending college, for his chapters are largely devoted to the representative men of letters whose works have both molded and reflected Southern history. Still, I wonder if “cultural historiographer” would not be a more accurate way of describing Simpson. What he says of Elizabeth Madox Roberts might apply to himself: he is more interested in the idea of history than in history itself. For example, he establishes Robert Penn Warren as the paradigm of a type of Southern sensibility- of-exile he calls “the loneliness artist,” analyzing Warren’s long residence outside the South as a reflection of the “lifelong preoccupation with the tension between ideality and reality in American history,” a tension that would eventually fuel the plot of All the King’s Men. Like Warren himself, Simpson repeatedly returns to “the problem of the freedom and responsibility of the individual in a world in which the individual is conceived as at once the maker and the product of history.”

The regional concerns of a critic like Simpson have been sadly undervalued in recent times. Place as an important force in shaping a writer’s identity now attracts only a tiny portion of the interest bestowed on the holy trinity of race-class-and-gender. But for the Southern writer, place has always meant less a real sense of locale than the kind of idealized Eden that Thomas Wolfe apostrophized as “O lost!” It is appropriate that Simpson closes his book with an epilogue titled “A Personal Fable: Living with Indians,” recounting his childhood in the northwest Texas community of Jacksboro and relating a good deal of fascinating family history along the way. Speaking of a local historian, one Ida Huckaby, the author of Ninety-Four Years in ]ack County, J 854-J 948, Simpson observes the tragic knowledge that every historian learns, “that in working to reconstruct out of memories and documents the wholeness of the past, one must come to suspect that the motive is illusory.” As he says of the hometown he has described in loving detail, “The image of Jacksboro that comes to me is of a place that no longer exists save in remote semblance. It returns because this town, however imaginary, is still the center of the world for me.” Simpson turns 80 this year, and one hopes that the valedictory tone of this concluding piece is premature.

In the fall of 1992, I attended a celebration honoring the centennial of the Sewanee Review. Brooks and Simpson were both there, along with Andrew Lytic, Shelby Foote, Helen Norris, Monroe Spears, Louis Rubin, and others who had contributed to that magazine’s estimable history and to Southern letters in general. In the autumn of the year on that lovely Tennessee mountaintop, it was not possible for me to look at these elder statesmen, still defending in some inscrutable way the inalienable autonomy of the South, without recalling “An Ancient to Ancients,” Hardy’s elegy for his own generation that turns on the melancholy refrain We are going, gentlemen. A great generation is going, and our world diminishes as it does.

[Community, Religion & Literature, by Cleanth Brooks (Columbia: University of Missouri Press) 334 pp., $34.95]

[The Fable of the Southern Writer, by Lewis P. Simpson (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press) 249 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply