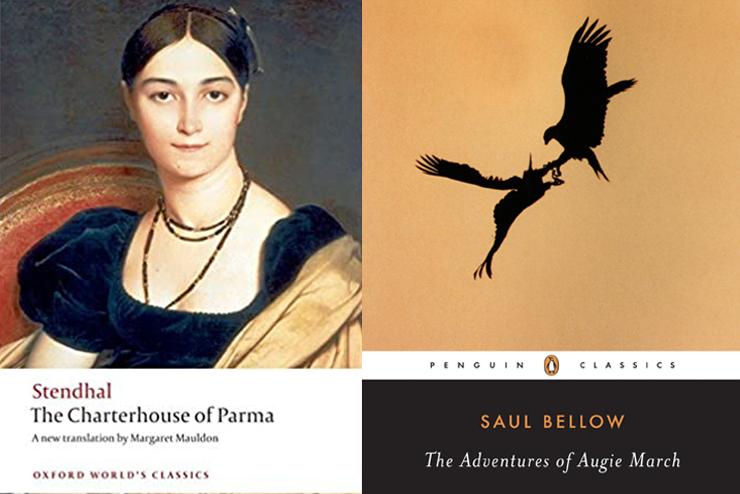

Stendhal was the pen name of Marie-Henri Beyle, who adopted it from the name of a German town he had seen with Napoleon’s army. His 1839 novel of the Napoleonic era, La Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma), was welcomed by a favorable and important review by Honoré de Balzac, and André Gide, an astute critic, included it among his top ten “desert island” novels. Like Stendhal’s earlier Le Rouge et le noir (The Red and the Black), La Chartreuse is a political and social novel, realistic, but with a romantic hero who cultivates his individualism, and who is a contrarian without realizing it.

La Chartreuse showcases Stendhal’s understanding of human nature. He is concerned both with social dynamics and the basic human qualities underlying them. Like Proust, who wrote 80 years later, Stendhal knew the mechanics of society were nearly constant, whether at the “court” of an old provincial hypochondriac who ruled from her bed, or at Versailles under Louis XIV. Political struggles and rivalries in Parma in the late 1790s and early 1800s were not unlike those in Washington, D.C. today. The aristocracy, weak and self-indulgent, and the arriviste bourgeoisie are governed by vanity and ambition, hence dishonesty and hypocrisy.

The young hero, Fabrice, a naïf, tells his aunt Gina’s protector, Count Mosca, that justice should be rendered by magistrates incapable of bending to pressure and emoluments. “Please give me the addresses of such magistrates,” replies Mosca. When Gina observes to Mosca that a useful mariage de convenance he has suggested for her with a wealthy old aristocrat is “immoral,” he replies, “No more than everything else done in our court.” Fortunes change rapidly; a minor incident can topple a minister. Spies, poisoners, and hitmen lurk. Sound familiar?

The concerns of La Chartreuse are, however, not only political and social. It is a highly personal novel expressing Stendhal’s vision of happiness. That vision included le naturel—spontaneity, authenticity—as well as natural and artistic beauty. Feeling is paramount for Stendhal. Even his depiction of the Battle of Waterloo—one of the book’s most splendid episodes—is personalized, conveyed at ground level as the disorganized experience of Fabrice, rather than a historical set piece.

Likewise, the novel is romanesque in its cloak-and-dagger elements and its intrigues of love. Stendhal was an idealist, not just a realist—the type who understands hurt but cannot avoid it. The true feelings Fabrice must hide are the author’s own. Thus Stendhal’s modern self-consciousness, a sense of irony, and frequent textual qualifications are among the novel’s literary techniques.

La Chartreuse was a compensatory exercise for Stendhal. Disliking his father, he made Fabrice, whose putative genitor is cruel, in actuality the son of a dashing Napoleonic soldier—a connection only observant readers will divine. And the author’s scorn of vulgarity in reality inspired him to create relief through his beautiful Italian landscapes, and in characters who remain true to themselves.

—Catharine Savage Brosman

The Great American Novel has two aspects. First, it has to celebrate the United States, to explore its nature, and its greatness or, perhaps, the marked lack of same. Second, it has to be a great read.

Perhaps we should admit that if what makes a novel truly great is an artful combination of plot, characterization, and philosophical comment, there are no American works to match the European products of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Trollope, George Eliot, Dickens, Balzac, Stendahl, Flaubert, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell, or even Iris Murdoch and Robertson Davies.

Nevertheless, Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country, and Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel clearly rank as masterpieces. And there are other consensus candidates: The Scarlet Letter, Moby-Dick, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and The Great Gatsby. All four explore vital aspects of the American character, even as all four focus on a small region of the country, with limited casts of characters from narrow segments of American life.

Another question is whether any American novelist might actually qualify as a proponent of the kind of paleoconservative, Old Right values which readers of this magazine embrace. Probably not, but there may be one who comes close: the Canadian born, Chicago-dwelling Saul Bellow.

Bellow authored 14 novels of uneven quality, but there is one that two splendid English contemporary writers, Martin Amis and Christopher Hitchens, nominate as the clear choice for the Great American Novel: The Adventures of Augie March (1953). The title expresses obvious homage to Mark Twain, and like Huckleberry Finn (and Don Quixote, and Tom Jones), Augie March is a picaresque. Born in a humble Chicago neighborhood of Jewish immigrants, the book tells of Augie’s mentors, his struggle to find a worthy calling (he tries being a small-time crook, a dog groomer, a university student, an eagle trainer, and a clothing salesman), and his equally frustrating attempts to find love, meaning, and nobility.

The book is peppered with historical and classical allusions at a level rarely achieved by American authors. Through his hero’s pitfalls, Bellow provides in sparkling prose a clear and transcendent joy that’s uniquely American.

—Stephen B. Presser

Leave a Reply