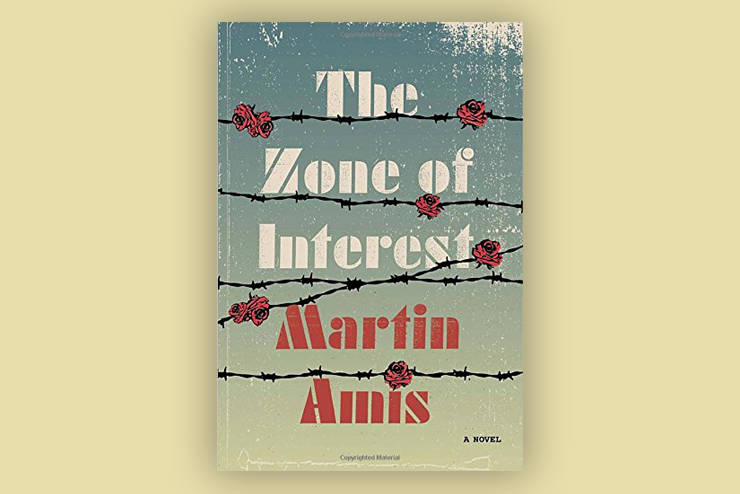

The novelist Martin Amis is the son of Kingsley Amis, whose Lucky Jim (1954) was a spectacular success. Noting the father’s “brilliance and ‘facile bravura,’” Atlantic critic Geoffrey Wheatcroft asserted that Martin “misunderstood his hereditary gifts when he turned from playful comedy to ‘the great issues of our time.’” Among his “great issues” is that of Nazi concentration camps, given masterful treatment in The Zone of Interest (2014).

The German philosopher Theodor Adorno is purported to have said that after Auschwitz, poetry became “impossible.” Literary critics, George Steiner among them, tend to condemn as barbaric, even immoral, all writing about the “Final Solution” and its implementation; the Holocaust can be represented only by linguistic silence. In 1945, Elie Wiesel, a Jew interned in both Auschwitz and Buchenwald (and later a Nobel Peace Prize laureate), vowed not to write about the subject for 10 years, saying, “I was afraid that words might betray it.” He finally published La Nuit (Night) in 1958.

Thousands of other witnesses have spoken; historians have written reams. Yet for an outsider to reproduce the “concentrationary universe” and its mechanisms still offends many. Claude Lanzmann (maker of the Holocaust documentary Shoah) called attempts at explanation “obscene”; Primo Levi’s brutal camp guard said: “Hier ist kein warum” (“Here there is no why”).

Amis’s literary and moral imagination met the challenge of this extraordinary topic. The Zone of Interest is among the finest novels of Nazi horrors I have encountered—and I’ve read many in connection with my research on French war literature. The novel is exceptional for its use of narrative viewpoints, those of the Nazis themselves and of the victims forced to serve them. One must understand Nazi psychology to write persuasively from their position, and that is no mean feat. Amis conveys the norm of Nazi thinking and actions, truly capturing what Hannah Arendt described as the “banality of evil.” Daily routines, common concerns (wives, children, food, drink—usually of good quality—sexual desire, ambition) survive even as mid-level Nazis carry out methodical exterminations amid crematorium odors and the sounds of screams rising from the cellars.

Amis’s novel exists not to entertain us, but to help us grasp how events unfolded and partly, perhaps, why.

Leave a Reply