Milk cartons carry expiration dates. But, for obvious reasons, they don’t need them. History books don’t carry expiration dates. But, for less obvious reasons, they do need them. History books expire when archival discoveries supplant earlier narratives or when new interpretive theories emerge.

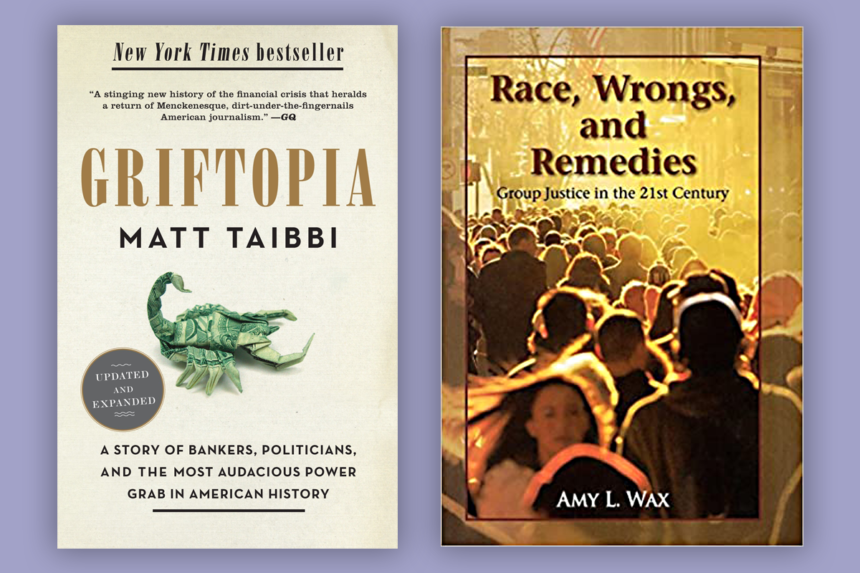

Lucky for historical posterity, decades more will have to pass before Matt Taibbi’s Griftopia expires. Taibbi’s acerbic prose mimics the little boy who pointed out the king had no clothes, but only if that lad had first swallowed three gallons of coffee and a mouthful of yellow jackets. Written ten years ago, the still-fresh Griftopia reminds readers in 2021 why American deplorables who suffered the destruction of their livelihoods, lifestyle, and culture voted for wholesale change in 2016 and 2020. Taibbi details Wall Street swashbucklers’ rapacious assault on middle America with sarcastic humor and painful specificity. Despite his reflexive hatred of “Tea Baggers” and the right, red staters can still ally with this enemy of their enemy as he takes down those who took down the global economy.

Griftopia will both enlighten and enrage you. Its seven raucous chapters skewer Alan Greenspan as “The Biggest Asshole in the Universe,” Wall Street banks, and unbridled greed. Taibbi explains the arcane roots of the crisis in terms even the financially illiterate can easily grasp. He dispels the lies and deceit the regime propagated to explain July 2008’s $149 oil price spike and subsequent December $33 nadir. And he dissects Obama’s healthcare reforms with surgical precision, so much so that readers will need to call a doctor for immediate sedation lest their every cerebral blood vessel explode from outrage.

Woke readers should consult their psychotherapists, The New York Times, and Ibram Kendi for antidotal instruction on how to process Taibbi’s harsh language. Griftopia contains a Blazing Saddles quote that includes the racial epithet worse than both World Wars’ combined destruction and a sexual expletive that should get him banned for life from all Gay Pride Parades. Mature adults can read on, recognizing the terrifying gravity of his substance outweighs his occasionally puerile form.

Taibbi’s final prediction deserves an A+ for prescience. Based on the Obamacare fiasco, he foresaw an economy where companies “compete in political influence” and manipulate the state’s power “to protect markets and force customers into the fold,” long before Amazon, Facebook, and Twitter substantiated his prophecy during the pandemic epoch.

—John Greenville

It is a lamentable statement about contemporary American culture that the most widely-read book written by a law professor on racial disparities is almost certainly Michelle Alexander’s egregious The New Jim Crow. Instead, it should be Amy Wax’s courageous Race, Wrongs, and Remedies, which offers a devastatingly concise annihilation of the entire intellectual framework on which specious “systemic racism” arguments like Alexander’s are predicated.

Wax argues the systemic racism school is based on crude sociological thinking. This is a species of ideological dogma in which every human phenomenon is turned into an inevitable consequence of invisible, omnipresent oppression. Racist discrimination, in this perspective, is the only possible cause of all black achievement disparities.

This is an oversimplification of stunning simplemindedness. Stereotyping happens, but its effects are mild and contested. Blacks underperform on standardized tests and many employment qualifications exams, and the claim that all such tests are racist has been disproven by decades of research. Black schools and neighborhoods suffer resource deficits, but how much are these caused by discrimination and how much by the cultural and behavioral predilections of the people inhabiting them?

Wax focuses unflinchingly on the contribution to disparities made by glaringly self-destructive facts of black underclass culture: failure to marry and to remain married, weak commitment to academic culture and embrace of rebellious and even criminal roles and behaviors, a narrative of victimization that discourages effort and perseverance. These are fully within the ability of the black community to alter.

American society has little stomach for encouraging cultural adaptation, due to what Wax diagnoses as remedial idealism, or the idea that all harm can be fixed. It is true that blacks were treated comparatively poorly for much of the country’s early life. But this tells us nothing about how much of their current predicament can be traced directly or indirectly to that poor treatment. It offers no guarantee that the harm can be undone purely through actions of parties other than blacks themselves.

It may well be that any further improvement requires changes to black underclass culture and behavior. This might seem unfair, but it is reality. And an even sterner aspect of reality is that some victims never fully recover, and we have no other rational option but to find a way to come to terms with that.

—Alexander Riley

Leave a Reply