What makes a great novelist? Genius—the ability to see connections hidden from most of us—obviously helps, but if great novels are great commentaries on the human condition, then living in a rich, stimulating, and challenging environment may also be essential.

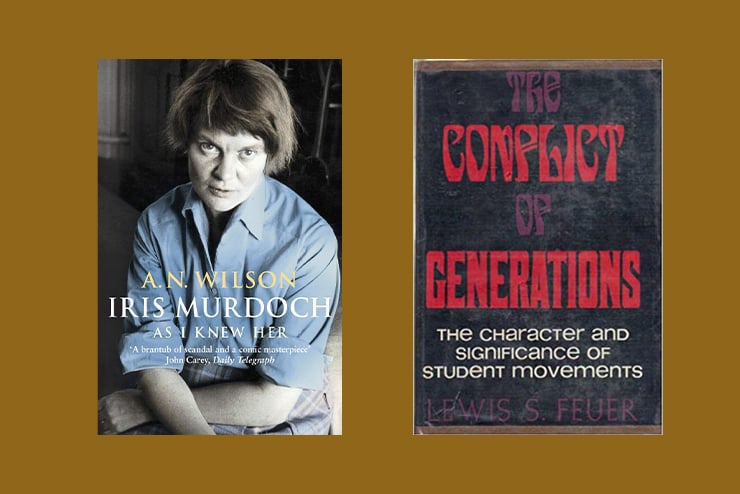

A.N. Wilson’s brilliantly unorthodox literary biography of Iris Murdoch—perhaps the greatest novelist writing in the second half of the 20th century—argues that the Anglo-Irish Murdoch’s success owes much to her innate talent, but also to her many lovers (of both sexes), as well as her long, albeit problematic marriage to another Oxford University professor and writer. She was also shaped by her experiences as a philosopher, her constant contact with virtually every other successful novelist in Great Britain, as well as her embrace of the West’s brightest lights, particularly Plato and Shakespeare.

As is perhaps true for all superb biographies, this one is also autobiography, and Wilson, who was selected by Murdoch as her official Boswell, self-consciously reveals both a truly extraordinary love and not a little bit of envy for his subject. Murdoch’s greatest work may be The Black Prince (1973), a novel about two novelists, one, Arnold Baffin, wildly successful and another, Bradley Pearson, deeper, and conceivably more astute, but unable to produce and consumed with possibly murderous jealousy of his intimate and protégé, Baffin. Bubbling only slightly below the surface of Iris Murdoch: As I Knew Her (2003) is the suggestion that Murdoch is Baffin to Wilson’s Pearson.

Wilson is the author of acclaimed biographies of political, literary and religious figures, a brace of novels, and controversial books on Darwin and Hitler. Like Murdoch he’s probably a genius, but unlike her, he never won England’s coveted Booker Prize, nor was he celebrated with quite the reverence received by Murdoch.

Wilson is a dazzling writer and his pyrotechnic brilliance is on full display in this examination of Murdoch’s life, successes and failures. Acclaimed as a minor masterpiece of wit, humor, and perception in England, it is almost unknown in America. It is probably the best introduction not only to Murdoch, but is an extraordinary antidote to the sterile and crabbed sort of literary analysis that prevails in our time.

The book is also a splendid survey of the best of 20th century English literature and philosophy and a remarkable study of passion, creativity, human frailty, character, morals, and politics. One finishes convinced that both Murdoch and Wilson belong in the timeless company of Dickens, James, and Joyce.

—Stephen B. Presser

In the fall of 1969, the already rapid descent into insanity of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) picked up speed. Waves of would-be college revolutionaries gathered in Chicago for the “Days of Rage.” They marched menacingly on the residence of the U.S. District Judge Julius Hoffman, who was at that time hearing the conspiracy trial of the infamous Chicago Seven. They viciously attacked police in an effort to “bring the Vietnam War home.”

By the following year, the Weather Underground had emerged from the corpse of SDS, and student radicalism of the ’60s had reached its logical destination. Eventually, these terrorists would carry out bombings of both the Pentagon and the U.S. Capitol.

It was in that same year that Lewis Feuer, then on the UC Berkeley faculty, published The Conflict of Generations, an account of the ’60s student movement from its origins to its violent apogee. At what Feuer described as “the freest campus in the country,” there emerged a so-called Free Speech Movement that was in fact already identical in outlook and approach to earlier revolutionary youth movements.

For the Berkeley radicals, free speech was perfectly compatible with the forcible disruption of opposing speakers and political meetings. The utopian concept of participatory democracy was used as a strategic tool, enabling militant minorities to impose their will on majorities. Tolerance for violence was observable even early in the movement’s life, and many of its wild-eyed leaders were nonstudent professional revolutionaries.

Despite the more than a half century since its publication, Feuer’s book is still the single most important study of student and youth revolutionary movements. A former Marxist who had moved rightward, Feuer covers the entirety of their history, including a long chapter on the radical Russian students’ crucial contribution to the Bolshevik Revolution and its consequent insanities.

At the core of such movements, always, are psychological processes of utopian youthful rebellion against tradition and elders, exacerbated by the decay of cultural norms and growing social class conflicts. Feuer wrote, “The will to revolt, the ‘alienation,’ was present long before a causa belli [sic] had been defined.”

—Alexander Riley

Leave a Reply