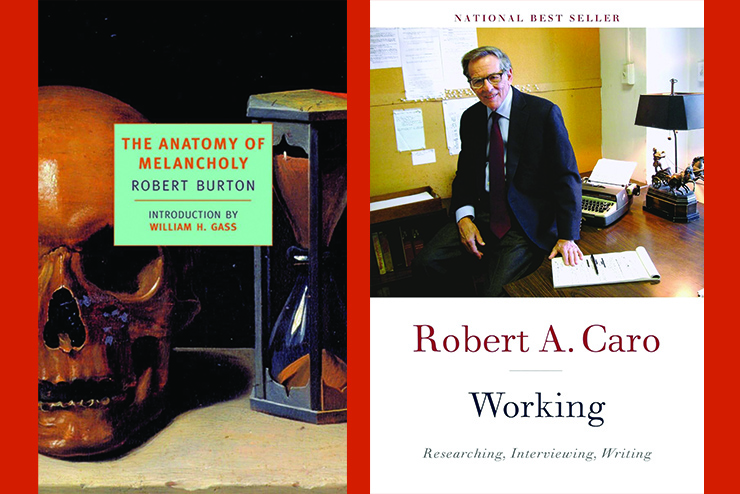

Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in 1621, may have an uninviting title, but it has always exercised a spell over men of letters. Burton (1577-1639), an Oxford parson of scholarly and solitary habits, wrote the book to relieve his own fits of melancholia. It went into five editions in his lifetime and has since informed and uplifted readers like Milton, Johnson, Sterne, Byron, Keats, and Anthony Powell; my copy once belonged to the English literary critic George Parfitt.

Melancholy was more than what we now clinically call “depression,” but was rooted in Greek notions about the four humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm) and “four temperaments” (sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic) that needed to be kept in balance to ensure mental and physical health. By Burton’s time, melancholy had become an attitude as well as a real state of mind, reflected in much art and literature of the period. We read his book now to take the temperature of early 17th century England, but even more because it is paradoxically a joy to read. It is a “lucky-bag,” enthused the bibliophile Holbrook Jackson, a receptacle of rich classical and Renaissance learning, expressed in magnificently mordant style.

For Burton, melancholy was a philosophical standpoint from which he viewed the human condition with equanimity as well as empathy. His lists of happenstances hypnotically unroll like rivers: “wars, plagues, fires, inundations, thefts, murders, massacres, meteors, comets, spectrums, prodigies, apparitions, of towns taken, cities besieged… New books every day, pamphlets, currantoes, stories, whole catalogues of volumes of all sorts, new paradoxes, opinions, schisms, heresies…weddings, maskings, mummeries, entertainments…”

He interlards his text with endless allusions or references to ancient events, Greek and Latin myth and thought, medieval lore, humanist scholarship, and early modern medicine, in a torrent of imagery, metaphor and simile that will compel most of us to consult our classical dictionaries. He was always an author for more adventurous readers. He encourages us to see our own conflicts or torments in grand context, whether diseases of the flesh or diseases of the mind. Our bodies are at one with the body politic and in harmony with the universe, and even emperors have felt the same desires, excesses, humiliations, joys, loves, pains, and sorrows we all know so well.

We swiftly discern behind his words a broad-minded, earnest, and good-natured observer of the human condition, whose abstraction does not preclude sincere sympathy for all of us in our imperfect and imperfectible worlds. Burton’s melancholy is ultimately un-miserable, his sturdy Anatomy bearing the reader along untiringly and carrying inside itself its own consolation.

—Derek Turner

In his aptly titled memoir Working, Robert Caro, the great biographer of New York City urban planner Robert Moses and President Lyndon Johnson, offered, at age 83, insight into how he puts together his immaculately researched books.

Although it has been said that creativity lies in hiding one’s sources and methods, Caro—throughout Working—pulls back the curtain. As he notes in the introduction, he requires of himself that he write 1,000 words per day when he is actively assembling a book. This phase comes only after years of research in which he sifts through millions of pages of documents in places such as the Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library. The research phase isn’t complete until Caro listens to the stories, both good and bad, of those who knew the people and events he’s researching.

Through it all, Caro’s wife, Ina, to whom Working is dedicated, was his loyal companion, gathering papers for him at the Nassau County Courthouse when he was bedridden with a back injury, taking on a teaching job to pay the bills after he quit his job at Newsday to focus on book writing. They once sold their home to raise an extra $25,000 to finance a year’s worth of time for Robert to conduct more research.

For a man who “hated being broke,” Caro was unwilling to take shortcuts to get his books done quicker and cash in on the second half of his advances. He preferred poverty to compromising his craft. This meant forgoing trips to the dry cleaners, running out of credit at the local butcher shop, and living in less-than-stellar digs in the Bronx. If that is what it took to get his books right, then so be it. It is also what led him to move to the Texas Hill Country for three years so he could comprehensively research Johnson’s life. No cutting corners.

When I was studying political science, the consensus among my professors was that there was no greater political biographer than Robert Caro. They were right. It is not often a biographer’s name precedes the suffix “esque,” but in Caro’s case this is most deserved. Some readers might prefer not to know how the proverbial sausage is made when it comes to Power Broker or his series on Johnson, but for those who do, I am not aware of any better insight into the craft of biography than the one provided in Working.

—Erich J. Prince

Leave a Reply