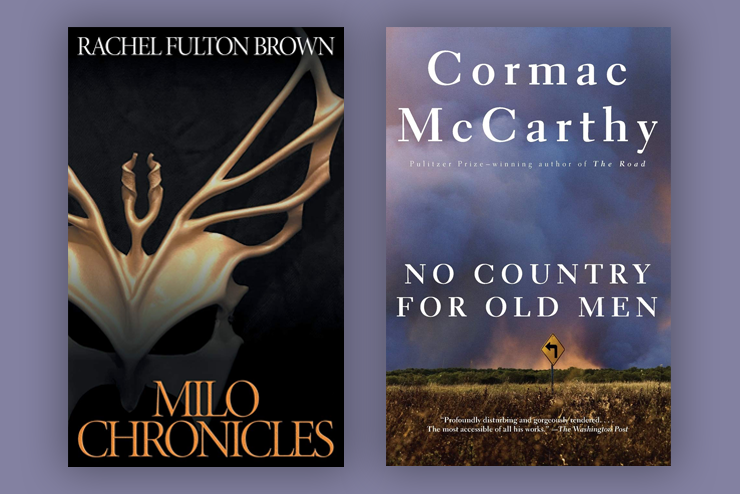

This extraordinary tome proposes a cure for our cultural illness: the resurgence of the muscular Christianity that once permeated higher education. The success of Fulton Brown’s project is far from assured, but in this essay collection she embraces the task with zealous ecstasy.

The book is ostensibly the story of the author’s unlikely relationship with Milo Yiannopoulos, the colorful former Breitbart journalist, who was once outlandishly gay, and who remains a professional provocateur. Among the many other delights of this book is a sustained repudiation of claims that Milo is racist, sexist, misogynistic, homophobic, a white nationalist, anti-Semitic, etc. Fulton Brown shows how Milo’s campus critics were terrified by his message: “The issues that Milo talks about are usually considered political, but in fact have to do with people’s deepest convictions: the proper relations between men and women, the definition of community, the role of beauty, access to truth.”

Her key insight is that behind Milo’s outrageous persona is a deep Christian faith. Almost no one took Milo seriously, but Fulton Brown did, sensing a kindred spirit. Both threaten to replace the academy’s predominant obsession with victimhood, multiculturalism, race, class, gender, socialism, and Marxism with a deeply Christian spirituality. It would be one of the greatest of uphill climbs to do so, but one of Fulton Brown’s strengths, as a tenured University of Chicago medievalist, is that of reminding us that in their medieval origins, our great universities were religious.

The essays amount to something like a manual for isolated conservative academics. From Fulton Brown’s observation of Milo, we learn how to deal with hecklers and cancelers, and how to ridicule the virtue signalers and the pernicious purveyors of intersectionality and identity politics.

More to the point, Fulton Brown manages to communicate, as perhaps only a medievalist with a surprisingly common touch could, that the good life cannot be lived without the kind of spiritual satisfaction and devotion to the common good that she finds prevailed in the Medieval period, and which lasted through the founding of the universities. This book, though aimed at a wide audience, might also be seen as her attempt to communicate that insight to her colleagues, who have unwisely scorned her and Milo.

—Stephen B. Presser

When students hear me introduce No Country for Old Men as a deeply political novel with a right-wing position on contemporary American society, those who have seen the film adaptation by the Coen brothers perhaps wonder if the movie and the Cormac McCarthy novel are unrelated entities that just happen to bear the same title.

What they most notice about that film is its spectacular violence and the terrifying, evil charisma of Javier Bardem’s portrayal of insane murderer Anton Chigurh. But neither Chigurh nor Llewelyn Moss, the doomed man he pursues, are McCarthy’s central characters. The novel is about the spiritual journey of Sheriff Ed Tom Bell and the demonic chaos within a culture that has rejected the values of his ancestors.

McCarthy places Bell’s religious faith front and center. It is, to be sure, a flawed, imperfect faith, but Bell aspires to be a purer man of God, and he reflects much, with deep gratitude and admiration, on the nearly saintly model of quietly fervent Christianity provided by his wife. Her presence in his life keeps Bell sane in the lunatic world in which he works, and he loves her with all his heart and soul.

McCarthy’s view of the world is thoroughly conservative. In his view, we inhabit a corrupted realm. Violence and death are the rule, made tolerable only by time-tested values and restraints that have now come undone. And yet the world is still electric with the presence of the sacred, even if it is a presence at times occluded and hard to detect through the calloused sensory organs of fallen creatures.

The sheriff reflects at length on the ways American culture has gone off the rails. What happened? Too much to easily describe, yet McCarthy manages it succinctly and effortlessly, in Bell’s rich vernacular:

It starts when you begin to overlook bad manners. Any time you quit hearin’ ‘sir’ and ‘mam’ the end is pretty much in sight… The old people I talk to, if you could of told em that there would be people on the streets of our Texas towns with green hair and bones in their noses speakin a language they couldnt even understand, well, they just flat out wouldnt of believed you. But what if youd of told em it was their own grandchildren?

At the novel’s conclusion, Bell dreams of his deceased father calling to him to shelter in the night. Though Bell wakes from his dream, the reader senses that it presages their anticipated encounter in glory in the world to come.

—Alexander Riley

Leave a Reply