During his prolific career, M. E. Bradford published eight essay collections, any one of which can be read and reread with profit.

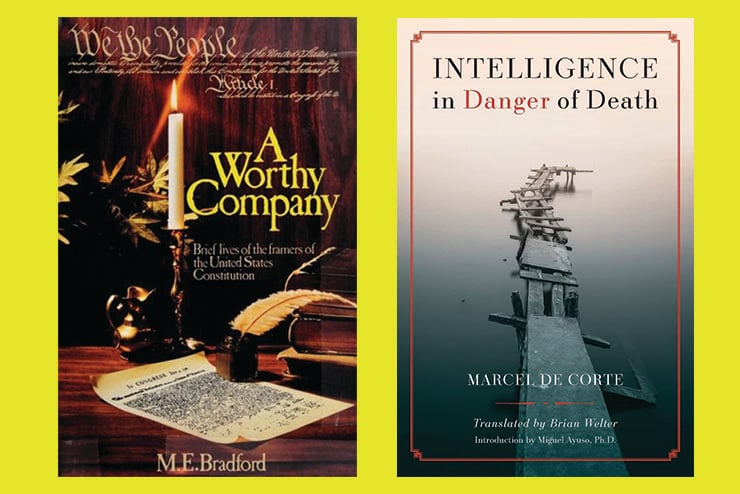

Just to take one example, consider A Worthy Company, an astounding achievement containing mini biographies of each of the 57 men who signed the U.S. Constitution. In this book, Bradford proved conclusively that the founders believed in a thoroughly decentralized regime and the primacy of Christian morality.

There is also Bradford’s most accessible volume, Remembering Who We Are, a 1985 collection of his writing from the previous two decades. If a genius is someone who can master two genres at once, then Bradford, as Clyde Wilson once maintained, exceeds that qualification. In addition to his mastery of literature and history, he was an insightful polemist, a man who knew his native Southland county by county.

A successor to the Vanderbilt Agrarians and Richard M. Weaver, Bradford’s conservatism was far-reaching and life-affirming. He stood in the tradition of Russell Kirk, who explained that conservatism, far from being grumpy and backward-looking, was a worldview fascinated by the variety of life.

Bradford had one foot—or maybe even both—in the past. In “Faulkner’s Last Words and the American Dilemma,” he quoted his favorite novelist: “Let the past abolish the past when—and if—it can substitute something better; not us to abolish the past simply because it was.” Faulkner knew the barbarians were around the bend. The bitter irony is that during the 1950s, Faulkner, along with Robert Penn Warren, sided with a liberalism that was not merely for civil rights but also wanted to obliterate the Southern past, an ulterior motive Weaver instantly recognized.

When it came to Bradford’s politics, culture took precedence over mere economics. “I have seen a county carried by two choruses of ‘Dixie’ played from a loudspeaker on a moving flatbed truck,” Bradford recalled in “The Lasting Lesson of Southern Politics.” Bradford probably would have been scandalized by Trump’s language. But, recall how Trump boasted that his plan to restore the name Bragg, after a Confederate Army commander, to America’s largest military base would help him win North Carolina. That Trump has fulfilled his promise would have, I think, won Bradford over.

—Joe Scotchie

The Belgian neo-Thomist philosopher Marcel De Corte was a Catholic intransigent for whom preindustrial society, thought, and culture set an enduring standard. That position is not immediately practical, but it enabled his penetrating critique of modern thought in Intelligence in Danger of Death, published in French in 1969 and newly translated into English.

Philosophically, De Corte was a common-sense realist. He took it as a given that a table is simply the table we see. He associated that view with peasants and others who deal directly with physical realities and who see themselves as part of a natural order they did not create. So he thought it proper to a mainly agrarian society with an enduring connection to nature.

That position led to his critique of scientism. The table modern science presents is a model summarizing measurable features of the table, like the results of various procedures it might be subjected to. The physicist’s table therefore presents an imaginative construction rather than reality. But the practical success of such scientific models has led people to see them as true representations of reality, and the scientific model has become accepted as the uniquely rational way to understand man and the world.

That tendency leads to problems when extended to social life. There, the same imaginative scientific models are accepted as true representations of reality. But outside the laboratory, the models’ predictions cannot be verified reliably, so the reasons for accepting them become irrational. The result is the death of intelligence—our ability to engage reality—and its replacement by imagination. So we now live intellectually in a world of fantasy we can remake at will. Thought thus becomes utopian, and intellectuals become makers of utopias.

De Corte’s commentary on the media is especially compelling. The decline of natural human connections and loss of a sense of reality based on personal engagement with concrete phenomena means that social coherence is now based on the mass media. Events and objects become socially real and comprehensible, and we gain the common understandings that make us a society, through the images and narratives the media supply. The result is a regime that dominates all society—increasingly including De Corte’s own Catholic Church—with a fantastic system of lies. “Democracy” becomes rule over imaginary collectives exercised by those who control information.

This great reactionary thinker has left us with a penetrating analysis of the relationship between technological rationalism, political fantasy, and the media.

—James Kalb

Leave a Reply