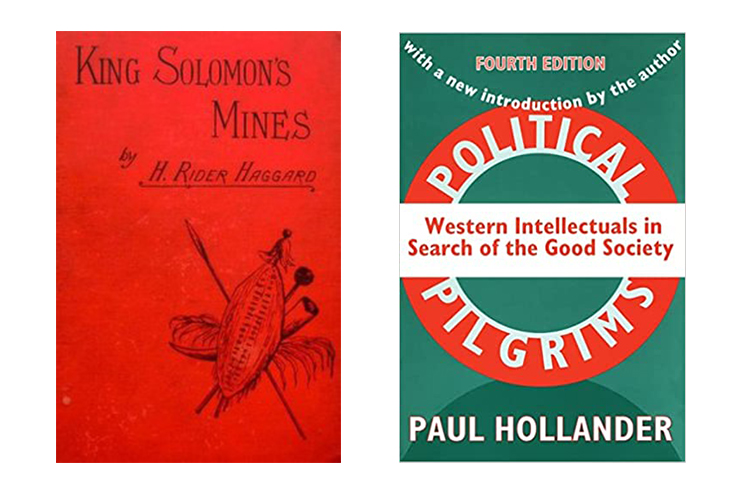

Those who like the Indiana Jones films and exotic, lost-civilization narratives—as well as anyone who recalls with pleasure the African adventures and cliff-hangers in episodic movie serials on Saturday mornings—can enjoy the chief forebear of these popular genres, H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885). Haggard wanted to put “grip” into his stories; he did not fail. With three Englishmen and a native or so, you will, using a crude, centuries-old map, participate in a daring expedition, proceeding from danger to danger. The purpose of the expedition is not to retrieve Solomon’s famous treasure but to find, living or dead, the brother of the Englishman who has financed the undertaking.

As Haggard’s lively style leads you on, you will cross a nearly-waterless African desert; you will witness a deadly elephant hunt; you will meet warriors of a mysterious, powerful tribe and their sadistic, bloodthirsty king, a mass-murderer, who usurped his throne, banishing the legitimate heir, a boy; you will observe a huge battle, on the outcome of which the heroes’ lives depend. In the company of a crone, you will find yourself in Solomon’s treasure chamber, confronted by an ancient, desiccated corpse and bedazzled by the wealth in precious stones (like that which Edmond Dantès finds on Monte Cristo).

But, when the crone makes the stone door panel, weighing many tons, crash down, you will be locked in without water or food. You will shiver there in the dark for hours, cold, hungry, desperate, abandoning hope of life and of finding the lost brother or the exiled boy-king. You can thus forget the cares of your own day.

This thriller draws on Haggard’s experiences during his two stays in what became South Africa. While important as a forerunner of exotic adventure stories, it stands out also in its context as a piece of Victoriana rivaling Stevenson’s Treasure Island (with which, Haggard admitted, he wanted to compete). The book, a best-seller, made Haggard famous, encouraging him in a successful literary career, even while he pursued a life in public service, for which he was knighted. Of the four motion pictures based on the book, the 1950 version with Stewart Granger and Deborah Kerr may be the best known.

—Catharine Savage Brosman

I periodically reread Paul Hollander’s magisterial study of the Western intellectual embrace of murderous totalitarian ideologies, Political Pilgrims. Every time, some new insight comes to me from the work. This last time, I was thinking about how professors who adhere to patently absurd radical belief systems bring undergraduate students into their cult. The grooming process looks eerily like what Hollander describes as the “techniques of hospitality” deployed by Communist regimes on Western intellectual tourists who undertook official tours of those states.

The ego massage is the first move. Prospective recruits are buttered up with compliments to make them amenable to later manipulations and to weaken critical faculties. Hollander recounts George Bernard Shaw’s being introduced by his Russian guide to two waitresses at a restaurant who just happened to be fans of his writing. The writer’s gullible response to this obvious setup: “Waitresses in England are not so well read as their Soviet sisters.”

On college campuses today, students are systematically set upon with a similar approach by faculty in various radicalized departments. Recitation of the hyper-simplistic mantras of Wokeism elicits excited praise; the highest grades are given for rote memorization of dogma and the merciless reduction of complex things into the brute credo of grievance and victimization. And trumpets blare over every move made by coveted potential majors with the correct intersectional identities. How can one fail to understand why so many such young people are taken in by these charlatans?

A second crucial Communist technique that has been avidly adopted by the radical professoriate and their allies in college administrations is the carefully engineered and selective tour. Tourists only see evidence of Communism’s triumphs—highly embellished when not actively fabricated—and all hints of its abysmal failure are expertly concealed. The deception must be consummately skillful, so highly trained liars are employed for the task. Hollander recounts Simone de Beauvoir’s stunningly naïve description of one of her hosts in Mao-era China, who the French critical philosopher believed “never [offered] a word of … propaganda from her lips” as she had “no need to tell fibs to herself or anyone else … she knows nothing of self-censorship.”

Today, the employment histories of past graduates in the radicalized humanities or social science fields are deftly hidden away from prying eyes. The parallel with the Communist era is of course no accident. The same intellectuals who received invitations from Castro and Mao wound up running the universities, and they now employ on new recruits to the faith the very methods that worked so well on themselves.

—Alexander Riley

Leave a Reply