The astronomer and mathematician Johann Doppelmayr (1677-1750) spent most of his life in Nuremberg, which had long been an intellectual and technical as well as political capitol. As a young man, Doppelmayr traveled to Germany, Holland, and England, meeting astronomers, mathematicians, natural philosophers, and physicists. He was a member of the Berlin Academy, the Royal Society, and the Imperial Russian Academy of Sciences. He was a globemaker and active experimentalist, as well as a professor of mathematics, some of whose students became mathematicians and makers of scientific instruments in their own right.

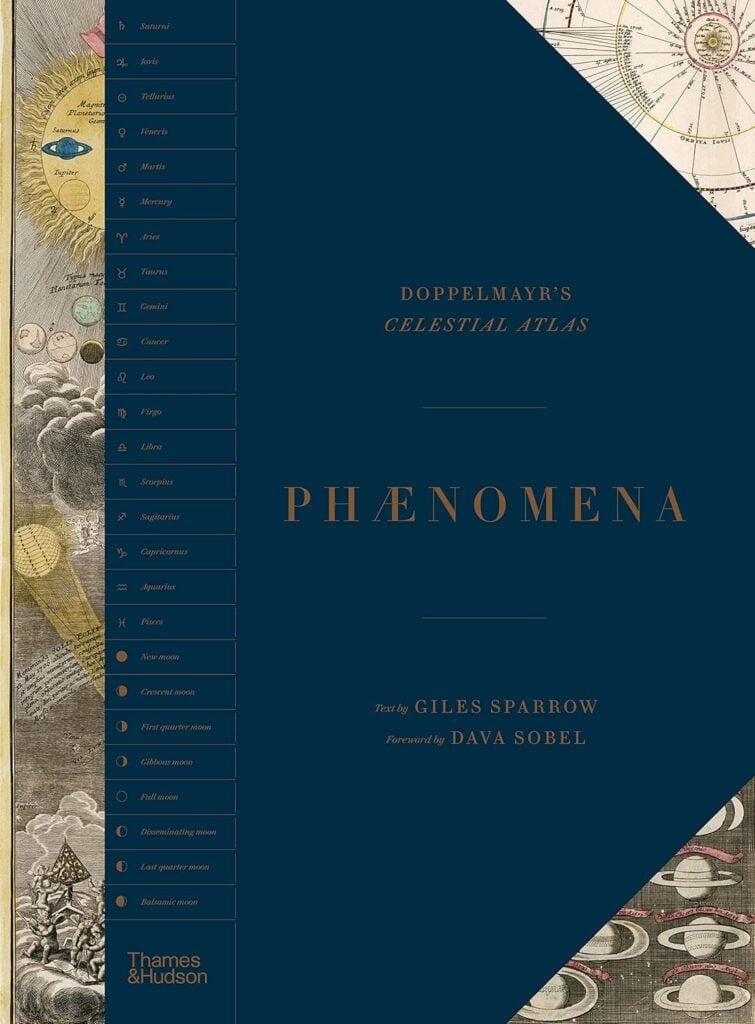

He published several books still useful to historians of science, but it is his Atlas Coelestis (1742) for which he is chiefly remembered. The Atlas was one of the great scientific achievements of the Enlightenment, sumptuously illustrated with star charts, tracks of comets, descriptions of eclipses, selenographic maps, projections of how the solar system would look from other planets, and diagrams illustrating the theories of Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Kepler, Mercator, Newton, Halley, and Riccioli, to mention just some. Giles Sparrow’s Phæonema (2022) is an appreciation of the Atlas, which is truly, as Sparrow enthuses, “a marvellous synthesis of art and science.”

In 1742, astronomy was not the icily abstract discipline of today but still had one foot in ancient cosmologies, classical allegory, Biblical literalism, medieval astrology, and Renaissance Hermeticism. In the pages of the Atlas, zodiacal figures cavort among careful calculations and cherubim carry quadrants, in a universe where heliocentricity was still not fully settled. Doppelmayr summarized the latest thinking of his day and, in so doing, helped clarify it.

The book is handsomely produced, with marbled endpapers and no fewer than 736 illustrations. There are reproductions of all 30 of Doppelmayr’s main plates, to which Sparrow has added other Atlas images and explanations that give context, and compare today’s knowledge with the theories of the time. One plate, for example, measures 1742’s ideas about the moons of Jupiter and Saturn against what we know now. Throughout, we find illustrations from medieval miniaturists and from the notebooks of Galileo and Huygens, as well as from Cassini, Dürer, Eimmart, Hevelius, Hooke, Kircher, and others, along with Doppelmayr’s own mesmeric mathematical drawings. Every page transports readers to an excitingly ever-expanding world of inquiry.

In a world increasingly ungrateful for the Western legacy and its scientific underpinnings, this is a splendid tribute to an influential artisan of astronomy and to earthbound polymaths who were blessed with soaring imaginations.

—Derek Turner

The field of children’s literature has been poisoned by invasive weeds sown by the morally nihilistic. Those of us with children know that you must plow over those rotten fields and return to a past when more suitable works were cultivated, before the toxic proliferation.

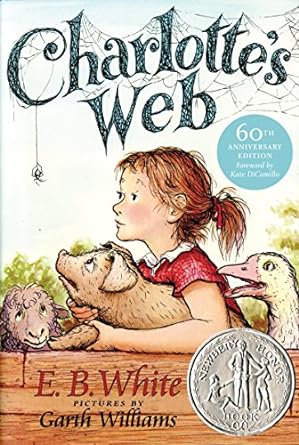

I recently reread one such book, Charlotte’s Web, with my youngest daughter, a decade after I reread it with her sister, and now five decades after I first encountered the book as a boy.

Where to start with the elements of this beautiful story? A first point in its favor is that Fern is a girl, a crown of daisies in her hair, and Avery is a boy, pockets full of frogs and fish. A girl and a boy, naturally, in exactly the way those two gender identifiers have been used in this society from the beginning until yesterday.

A second is the world of Zuckerman’s barn. This lovingly described place, in which Wilbur and his friends spend their lives, is a paradise that some of us can remember from our own youths. The smell of cows and pigs, the sound of the chickens, swinging on a rope hung from a rafter, swimming in a nearby pond: Every child should have such memories. The barn, White writes, “had a sort of peaceful smell, as though nothing bad could happen ever again in the world.”

The inevitable, melancholy passage of time and the humbling reality of death are treated in a manner that would have pleased my farmer grandfather. Like the Zuckermans, he timed the rhythm of his life by the natural hourglass of the passing of the seasons instead of watching the sand run out while running endlessly on a treadmill in pursuit of nothing important. The crickets sing their sad, annual song as Wilbur and Charlotte prepare for the fair, giving us a premonition of Charlotte’s death. Her passing is a great sadness, but the novel shows children that though all things must pass, love endures all things.

A minister tells the congregation, wondering over the appearance of words in the web of a spider, that “human beings must always be on the watch for the coming of wonders.” True, true. And in 1952, a wonder came into the world, courtesy of a writer named E. B. White. I am eternally grateful that it did and that I have been able to share this formative text with the two people who matter most to me.

—Alexander Riley

Leave a Reply