Northwestern Europe’s early development owes much to the Carolingian dynasty, which led Germanic society into Christendom from the dead end of paganism. It set the stage for the lush flowering of knightly culture, with its ideals of chivalry, courtesy, and courtly love, which established the Western habit of mind.

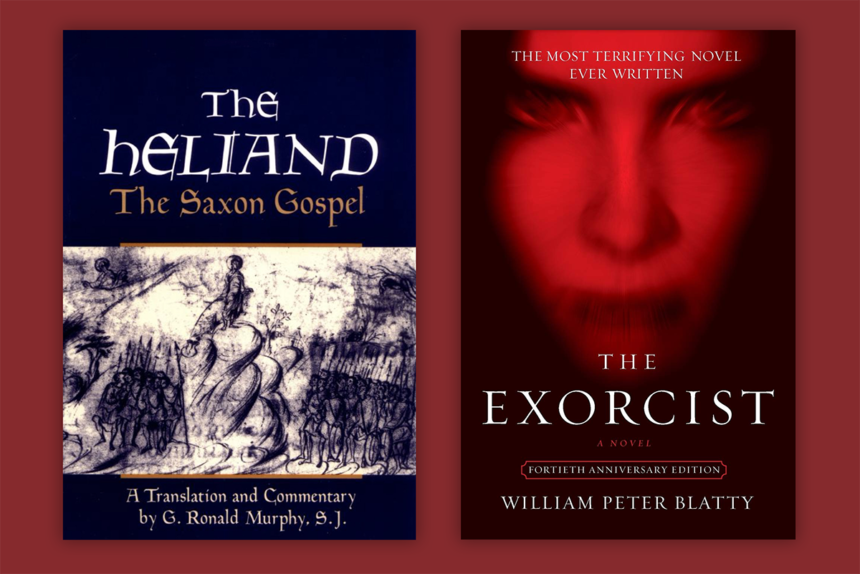

This Western ethos is rooted in classic literary works, and chief among these is the Old Saxon epic poem The Heliand, dating from the early ninth century and likely commissioned by Louis the Pious, the son of Charlemagne. The subject matter is the life of Christ, wherein loyalty, honor, courage, faith and love are defined. Its apt title, The Heliand (“The Savior”), is not original but added by the first editor in 1830.

At nearly 6,000 lines in length, the poem survives in six manuscripts, two nearly complete, one of which dates from the 10th century. Although the author is not known, we are told that he was a well-known master-poet and monk at the famed monastery of Fulda in what is now Germany. Though it appears to have been popular in its day, The Heliand remains largely unknown in the English-speaking world because of poor translations.

The first, published in 1966 by Mariana Scott, deploys an imagined Germanic vocabulary to the point of incomprehensibility. The second, in 1992 by G. Ronald Murphy, fails for a similar reason, in that a supposed hidden pagan meaning of Old Saxon terminology is “recouped” in the translation in an attempt to demonstrate that Christianity was “Germanicized” when it came North. The result is a Heliand transformed into Murphy’s thesis of the Saxons subverting Christianity by paganizing it.

Both translations destroy the grandeur and clarity of the original. Sadly, Murphy has much influenced the poem’s reception in the English-speaking world. The Heliand still awaits its true English translator.

But why read the poem today? Two important reasons. First, as a rather moving testament of faith, which prefigures in its structural complexity the Gothic cathedrals of a later age. Such religiosity we have entirely lost, whereby personal faith is the rich ground of beauty. Second, as a classic, The Heliand embodies another lost virtue—that of holy wisdom and its necessity to life.

Both reasons are fitting antidotes to the excesses of our own age; and both are reminders that man’s purpose is not to create heaven on earth. Or, as the Heliand tells us:

Then God’s angels go forth,

The holy guardians of Heaven, and gather together

men who are pure, and bring them into eternal glory,

into the clear light of Heaven…

—Nirmal Dass

It is one of the open secrets of the history of modern American popular culture that William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, which became that horror film of horror films, is in fact perhaps the most traditionally and conservatively Christian American novel ever made into a blockbuster film.

Some of the plot’s deeply Christian elements are present—often in visually moving form—in the movie, though they are routinely missed by viewers too distracted by Linda Blair’s frightful makeup and vomited pea soup. The effervescent and overtly symbolic moments include when Father Merrin, the heroic priest exorcist, stands opposite the statue of the demon with whom he will do battle at the film’s outset. And, when he mystically arrives at the MacNeil household and Regan’s mother, Chris, beholds him for the first time with bated, awed breath in that iconic fog-drenched scene. And, when he and Father Karras ascend the staircase to do battle with the demon and take on, in visual substance, the Christian spiritual quest to move upward from sordid flesh to holy spirit.

But much of the religious narrative was excised from the novel in the transition to the film. The chief plot device that gives away the novel’s affirmation of traditional Christianity is at the conclusion, which depicts the reaffirmation of Karras’ faith. This is also depicted in the film, but only obliquely. When Chris plaintively asks, “Will she die, Father?” these words steady him in his task.

In the novel, it is no spoken word of Chris, but rather a few written words of Regan that bring Karras back to God and give him the power to defeat the demon. While gathering his strength downstairs as Merrin continues the exorcism in the bedroom above, Karras sees a framed poem the girl has written to her mother. The verse alludes, in a childlike, innocent way, to the human outrage in the face of corruption, disease, and death, and to the realization that we must be made of something more than clay, for mere clay cannot begin to explain the love of the mother for the child and the child for the mother.

These words make Karras weep with compassion. His faith that love proves the existence of the human spirit, and thus eternity, and therefore God, floods back into him.

I have read the novel a dozen times with students over the years. That passage moves me too to tears, predictably, every time.

—Alexander Riley

Leave a Reply