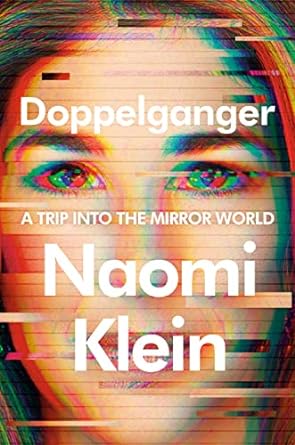

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World

by Naomi Klein

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

416 pp., $30.00

Montréal-born Naomi Klein is a prominent international voice of the left, an author of influential and often insightful books about capitalism and climate change. She has spent decades linking capitalism with an alphabet of other -isms, from ableism to Zionism. Her 2014 climate change political tract, This Changes Everything: Capitalism Versus the Climate, has been rewarded with plaudits in Canada and beyond, earning her a pleasant reputation as something of a sage.

How horrifying, then, for her to discover that she was being confused with another Naomi, one equally famous and loquacious but espousing rather different and (in Klein’s eyes) reprehensible views. The author’s alter ego is Naomi Wolf, once lionized for her 1990 feminist classic, The Beauty Myth, but who in recent years has taken (sometimes foolish) contrarian positions. Wolf has also associated with what Klein calls “some of the most malevolent men on the planet,” by whom she mostly means Steve Bannon.

This book is born of a very personal grievance, which ends in Klein’s not wholly convincing attempt at New Agey acceptance. More usefully, it also offers ponderable points about the interstices of ideology and individuality, the permeabilities of personalities, and modernity’s unhealthy obsession with images.

At the top of both authors’ Wikipedia entries is an underscored sentence: “Not to be confused with [the other Naomi].” Their names are even mixed up by the text-autocomplete functions of computers and cell phones. Confusion between two Naomis is hardly surprising in our age of distraction and dichotomy, when millions click to “like” or dislike articles they may not have read by author-avatars who bear superficial resemblances of appearance, profile, and rhetoric.

There are real resemblances, as Klein outlines, inadvertently amusingly: “We both write big-idea books… We both have brown hair that sometimes goes blond from over-highlighting (hers is longer and more voluminous than mine). We’re both Jewish.” As well as hairstyles, their areas of concern often entangle, from feminism to Occupy Wall Street. Both have been vociferous liberals, both have enjoyed stratospheric careers, and both can exhort with commitment and skill. They are similar in age and, at one point, even had partners with the same first name. But then—doppelgängers are always disconcerting.

She touches tantalizingly on doppelgängers across ages and cultures, from the changelings of medieval legend reemerged as Jungian shadow-selves to modern parallel universes, like the hapless laundromat operator in the recent film Everything Everywhere All At Once, who simultaneously exists successfully in other dimensions. Innumerable artists and storytellers have drawn fruitfully on the idea of people who are like-yet-unlike and who, for all their differences, also have unique understandings of each other—even the evilest of “evil twins,” like Dr. Jekyll’s Mr Hyde.

To Klein, the greatest evil twin of all is Western civilization, an original-sin conception in which everyone is complicit, and everything is tainted—where every old ill has 21st-century relevance. Through Klein’s looking glass lies a nastily dualistic Wonderland, “whiteness’s shadow world,” thronged with the monsters of history clawing their way into the modern world, from Christianity to Nazism—and, of course, Trump.

In her cheval glass, New York is a shiningly skyscrapered refraction of England’s old York, carrying over and amplifying its pathologies in the present. Even “purity” is impure, just as “beauty” was Wolf’s myth. Klein sees herself, and everybody, making idolatrous self-images, colonizing and consuming ourselves, turning personas into personal brands, always competing for attention and influence. Staring back at us from all screens is another version of us, as we’d like to be seen, or some hateful inversion: a winsome mirror image or a dead-eyed golem.

In 1991, Klein, then still a student, interviewed Wolf when the author of the just-published Beauty Myth was visiting her campus. Klein was “transfixed” by Wolf’s appearance; less so by her book (“We were already way ahead of her,” she sniffs). There was a startling exchange after Wolf’s speech when Wolf said to Klein, “You look like you’ve just been raped.” This was untrue, but it led to an intense, short-lived correspondence, and Klein still credits Wolf for giving her the confidence to write.

Klein’s criticisms of Wolf are written more in sorrow than anger. Rather than calling down contumely on Wolf’s big-haired head, she bemoans an ally lost to the Dark Side. There are, however, enjoyably catty asides. She notes that Wolf, asked whether she had written Klein’s The Shock Doctrine, denied it but was “flattered.” When Wolf found there was a Telegram account parodying hers, she complained it made her “look like a lunatic,” and as if she had “a tacky, blowsy, overdressed, grammatically-intolerable doppelgänger,” to which Klein adds an arch “Ahem.”

By examining Wolf’s choices, Klein hopes to prevent others from making similar choices, maybe even to stop society from sinking further into distrust, irresponsibility, paranoia, rivalry, and superficiality. Many will agree with Klein’s points about anomie, late-stage capitalism, environmental degradation, narcissism, and social media. They may also share her distaste for the strange coalition of hustlers, hyper-individualists, and quacks who came to the fore over COVID. She is also commendably candid about some of the left’s failures—their hypocrisy, lack of commitment to free speech, ossified thinking, and demonization of Trump’s “Deplorables.”

Klein nevertheless blames the right for debasing the political lexicon, though it has been the zealots of her side who have made everything political and leveled insults so liberally they now mean almost nothing.

Wolf is notoriously careless with data, quite apart from bizarreries about “fascist coups,” “global governments,” or “chemtrails.” Conspiracy theorists, Klein notes neatly, “get the facts wrong but the feelings right.” Society really is sick, and there really are forces working to make the world even worse than it is. Just because Wolf’s answers to such questions are often wrong does not mean that Klein’s subtler answers are right. Conspiracy theories and unhelpful outrage can be found on all sides. Deep passion is another thing shared by these Naomis. “I go through periods,” Klein groans, “when the impunity of it all gets the better of me…. My throat constricts. My breath becomes shallow. On bad days, I feel like I might explode.”

She scoffs at Wolf’s vaccine-skepticism, while claiming herself that COVID victims were “murdered,” and the virus amounted to eugenics. She also alleges there were murders of First Nations children at Canadian residential schools. While those schools were designed to erase indigenous culture, and children did die from neglect, no evidence of murder seems to have been adduced, and the total number of dead is undoubtedly exaggerated.

Klein blames Trump for anti-Jewish hate—although any rise in anti-Semitism since the incumbency of the president with Jewish in-laws, and who recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, is more attributable to homeward-looking Muslims of the kind she hopes America will continue admitting. Wolf’s worries that Biden has opened the borders are apparently “a lie,” which may come as news to those on the U.S. southern border.

Klein writes of “migrants left to drown to protect the fantasy of a fortressed Europe”—“boat after boat,” apparently. In fact, few boats have foundered, and angsty European governments make Sisyphean efforts to pick up migrants (who are often economic migrants rather than refugees), at vast cost. It never occurs to her that barriers may sometimes be necessary to maintain global diversity or that mass migration might imperil the social solidarity she seeks. Perhaps the conservative, cruel, cupidinous “forces of forgetting” she caricatures are just rallies of realists. She complains Wolf’s worldview only comprehends white, middle-class, and educated women; one might reasonably enquire how many nonwhite, non-middle-class, or uneducated women read Klein’s works.

“The known world is crumbling. That’s okay,” Klein assures us, but she offers no new world in its place. For someone easily capable of incisiveness, her Great Reset is short on substance. Her chief prescription seems for us all to lose sight of ourselves because “no one is quite as special or unique as we might have imagined ourselves to be”—a statement which, even if it were true, is not exactly inspiring. Klein’s concept of community is expansive to the point of incomprehensibility: “We have kin everywhere. Some of them look like us, lots of them look nothing like us … some aren’t even human. Some are coral. Some are whales.”

When she eventually thanks Wolf for freeing her from “the tyranny of my own self,” we can’t take her at face value. As she has already noted, there is an “inherent humiliation in … one’s own interchangeability and/or forgettableness.” Perhaps ostentatious self-abnegation is just a new kind of complacent self-regard.

Societies simply cannot be sustained on vacancy, or fleeting fist-pumping feelings of the kind she remembers fondly from a Bernie Sanders rally. Engaging in endless critique and picking at ancient sores and emphasizing every kind of “otherness” can result in nothing more than a permanent revolution of resentments. Whatever her excesses, whatever her errors, Klein’s more-bouffant mirror image has found at least some ground.

Happily, this cerebral author, in her remote British Columbia bolthole, will be largely insulated from any consequences of even her most utopian theories. She’s luckily free to smash all the mirrors in these ruins of the West, to shatter all silvered glass and blend herself completely into the blind, blank plate behind.

Leave a Reply