Ten years ago, it appeared that immigration restrictionists were poised to win some real political victories. In 1992, Pat Buchanan had raised the previously untouchable issue in his presidential primary challenge to George H.W. Bush. That same year, National Review, under the editorship of John O’Sullivan, joined Chronicles in calling for deep cuts in legal immigration. Two years later, California voters ignored their media betters and voted overwhelmingly for Proposition 187, the ballot initiative that would deny certain welfare benefits to illegal aliens. Bills restricting immigration had the support of numerous members of Congress.

By the summer of 1996, all of that momentum had collapsed. After Buchanan shocked the political world by winning the New Hampshire primary, he was savaged by the media with a tidal wave of hate-filled rhetoric unseen before in American history. Congress’s attempts to make mild cuts in legal immigration were defeated when 77 Republicans voted with open-borders Democrats. In time, O’Sullivan would be fired from National Review, and the author of this collection would lose his regular column at the Washington Times. Finally, in 1999, federal courts ruled Proposition 187 “unconstitutional,” a decision unopposed by California’s governing class.

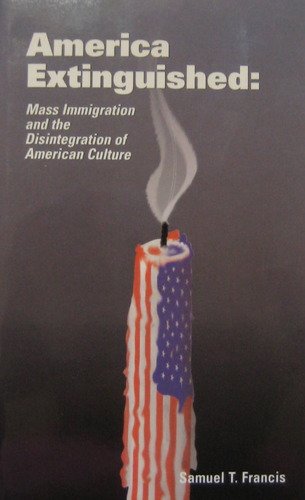

Samuel Francis’s collection of columns on immigration reflects this gloomy situation. His 1997 essay collection, Revolution From the Middle, allowed for some optimism that a Middle American populist movement might succeed. That volume had a blue cover with a flickering light at the center. The artwork for America Extinguished, on the other hand, shows a lighted American-flag candle in the process of steady meltdown.

Francis has not been the only writer to confront the immigration issue. However, no other columnist has written so relentlessly or so courageously on the subject. The 59 columns collected here attack mass immigration on economic, political, and cultural grounds. Largescale immigration floods the labor pool, driving down wages. Pro-immigration conservatives, usually in the employ of big business, complain about a labor shortage, especially in the area of high-tech jobs. In fact, no such shortage exists. Less immigration would mean higher wages for American workers. In addition, had massive immigration been halted three decades ago, there would be nine million fewer poor people in the United States today.

Where politics is concerned, immigration has helped to create the now-infamous red/blue American divide. The red zone is the traditional America ranging from West Virginia to Nevada, a nation far more conservative than the first-generation Texan it elected in 2000. Much of the blue zone (the East Coast and the West Coast, as well as urban centers in the Midwest) has long been liberal; nowadays, it is, among other things, as much hispanophone as anglophone and seethes with resentment of the heritage of 18th- and 19th-century America. The Republicans’ incessant pandering to the Hispanic vote, detailed by Francis, has only moved the GOP further to the left, allowing the party to accept the leftist status quo on immigration, affirmative action, and funding for bilingual education. And yet the Hispanic vote remains solidly Democratic. Meanwhile, benighted white males continue to form the base of the Republican electorate. For now, they have no place to go.

The most striking examples of how immigration and changing demographics have upended the Old America are apparent in the culture wars. California legislators consider an official holiday for Cinco de Mayo and another for the 1960’s radical Cesar Chavez. Meanwhile, events and symbols of Western civilization, most notably the Columbus Day parade and the Confederate Battle Flag, remain under attack from multiculturalist fanatics.

The rise of anti-Western ideologies is the cause of the restrictionists’ greatest frustration. Most Americans care nothing for the nostrums of multiculturalism; at the same time, they care little about preserving the Western culture that gave birth to our liberties. For the vast majority, it seems, “American culture” does not signify the political philosophy of Patrick Henry, the collected works of Mark Twain, or a national holiday for George Washington. Rather, it means whatever junk the television and film industry in Hollywood and Manhattan churns out.

Such complacency is not the restrictionists’ only dilemma. In the 1980’s, an immigration crisis existed, but it was confined mostly to urban areas. This is no longer the case. Now, once-pleasant small towns such as Dalton, Georgia, and Rogers, Arkansas, find themselves overwhelmed by illegals serving the cheap labor “needs” of American industrialists. Not to be outdone, the governor of Iowa, Tom Vilsack, recently concocted a plan that would bring no fewer than 310,000 Third World immigrants to that tranquil Midwestern state. The state’s “business and civic” leaders endorsed the plan, but a solid majority of Iowans strongly opposed it.

Does public opinion count for anything? Not even the events of September 11, 2001, could break through the immigration impasse. Why? “Mass immigration is a deliberate, politically created policy, deeply rooted in the material interests of the ruling elites of the United States,” writes Francis.

It serves to depress wages and lower labor costs for large corporations; it serves to replenish a dwindling number of members in labor unions; it offers entire new constituencies and voting blocs to the two established political parties; it provides a new underclass for which an immense welfare bureaucracy can deliver services and social therapy; and it promises a new “multicultural” society in which cultural elites, already deeply alienated from traditional American institutions, and vast new cultural and political ethnic lobbies can gain power. When a policy is as closely entwined with material interests . . . as immigration now is, it tends to become impervious to ideas and arguments, and it will take more than the terrorism of Sept. 11 . . . to change it.

Francis’s intention is not to drive the reader to despair but to action. Late as it is, grassroots political action can persuade the power elites to enact long-overdue policies. If even a small fraction of Americans were dues-paying members of the various anti-immigration lobbies currently at work in Washington, then such groups could have real clout. At present, the only grassroots action taking place is by Arizona ranchers. Fed up with the government’s refusal to patrol the border, they have armed themselves in order to defend their property from what is, literally, a foreign invasion. (The elites in Washington believe that the ranchers are the ones who are out of line.)

Still, it is likely that, grassroots activism or not, the Republican Party will once again be forced to address the immigration issue. If immigration continues at current rates, blue America will soon gain the political upper hand. And as already has happened in numerous small towns in red country, a blue culture will make great inroads into Middle America. Whether the GOP will do the right thing—and whether it will do so before it is too late—remains an open and very troubling question.

[America Extinguished: Mass Immigration and the Disintegration of American Culture, by Samuel T. Francis (Monterey, VA: Americans for Immigration Control) 215 pp., $6.95]

Leave a Reply