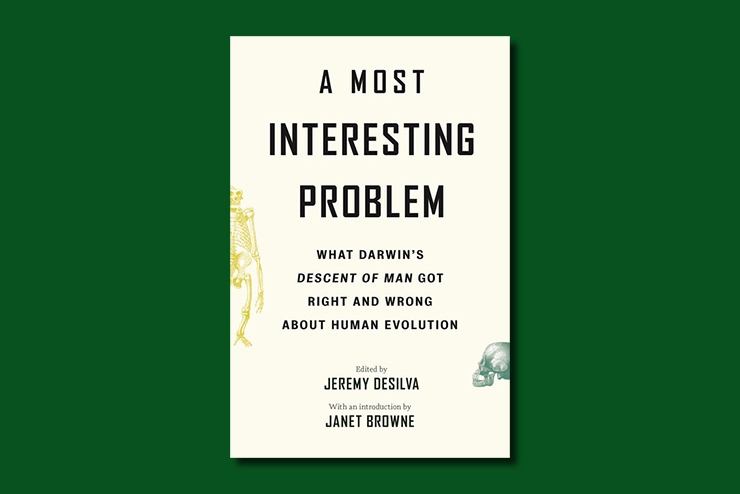

A Most Interesting Problem: What Darwin’s Descent of Man Got Right and Wrong about Human Evolution

Ed. Jeremy DeSilva

Princeton Universtiy Press

288 pp., $27.95

The complex debate about the place of Darwinian theory in discussions about humankind’s nature has been further complicated by an academic left that has taken up trashing Darwin—who is, after all, a dead white male—with as much vigor as religious fundamentalists.

A Most Interesting Problem presents itself as a collective reflection on the 150th anniversary of Darwin’s Descent of Man (1871). In that book, published a little more than a decade after On the Origin of Species, the great naturalist applied his framework for understanding the evolution of life to making sense of his own kind.

In the preface, editor Jeremy DeSilva admirably rejects a worshipful stance toward Darwin. There are no gods doing science, only human beings trained to collectively produce hypotheses and test and retest them. The scientist, as Darwin himself surely believed, must selflessly submit his work to the scrutiny of others who will attempt to disprove it.

But it is not enough for DeSilva, an anthropologist, that scientists commit themselves to the scientific method. “Science is a human endeavor,” he informs the reader,“…[that] stagnates when it is done by homogeneous scientists with similar backgrounds and experiences.” Contemporary academia’s cantillations of diversity, equity, and inclusion come through loud and clear here. But whatever its value for raising the emotional fervor of true believers, that statement is pure tripe.

Modern science’s discoveries are largely owed to a homogenous group of European men with similar backgrounds and experiences. The entirety of scientific history until less than a century ago was characterized by that homogeneity, and it was not stagnant as a result. On the contrary, thanks to the labors of these patently nondiverse individuals, it produced over several centuries the marvels of discovery and medical and technological progress of which we are all aware.

Dismally, many of the book’s chapters follow the preface’s lead, denigrating the possibility of an objective scientific method. We cannot “shed our skin,” another anthropologist, Holly Dunsworth, laments. We must accept our partiality. One of the giants of modern biology, E. O. Wilson, is attacked for suggesting that the properly scientific attitude is to imagine we are from another planet, discovering marvelous new things with which we are totally unacquainted and which we must think from the ground up.

How much harm has been done by this approach? Objectivity, it seems, presents opportunities for exploitation, while self-righteous moralizing has never been at all amenable to that, or so we are asked to believe. In Dunsworth’s view, objectivity is also “detrimental to science because it prizes those perspectives judged to be objective over others.” Well, yes, we ought to readily admit that it does. That is, it values perspectives that try to control for bias above those—like Dunsworth’s—so blinkered that they cannot even imagine undertaking the slightest effort to get outside of their perspectival prejudices.

Alas, this is neither the worst piece in the collection nor an outlier. Yet another anthropologist, Agustín Fuentes, agrees with Dunsworth that striving for objectivity in the study of humankind is a “poor move” and Darwin’s “first mistake.” Fuentes vigorously rejects Darwin’s belief that racially different human groups might be reasonably considered subspecies. But there is nothing inherently “racist” about such a notion; it simply means that, though all humans are members of the same species, they have important differences that derive from the process of natural selection.

Such differences would have arisen from significant periods of secluded breeding in which regional groups were separated from one another. This is the same phenomenon by which, for example, several subspecies of a species of bird can emerge because a body of water or mountain range effectively isolates them from one another long enough that evolution produces subtle differences in the separated groups.

We know now that such differences do exist in regional human populations along genetic lines, and we are at the very beginnings of studying their consequences. But Fuentes will have none of it. He peremptorily asserts that this is an effort that has no scientific utility. Moreover, it could only be embraced by “racists and separatists.” His claim against Darwin’s view is that humans are identical across more than 99 percent of our genome.

That is correct. But Fuentes does not note that it is also true humans are identical with chimpanzees across nearly 99 percent of our comparable DNA sequences. Surely, we would not deny substantial and meaningful differences that separate us from our closest primate relatives, despite the vast amount we share genetically. A small genetic difference can produce significant variation.

The real problem, Fuentes concludes, is that “Darwin was, like much of humanity, a biased human being…[and a] racist.” Well, of course! It goes without saying, does it not? The sermonizing proceeds apace: “So many humans are that way because the societies that raised them are deeply structured with racist, classist, and gendered divisions central to their histories and contemporary functioning.” Somehow, Fuentes and his colleagues have extricated themselves from this pernicious operation.

Alongside such tedious “woke” preaching, the contributors to DeSilva’s book do offer some useful insights. Michael Ryan, a zoologist, gives a nice accounting of Darwin’s contribution to the question of the aesthetics of beauty in sexual attraction. As it turns out, his suggestion that female animals discriminate among potential mates in aesthetic terms has been supported by recent research. Additionally, John Hawks looks carefully at Darwin’s efforts to group humans among the other primates and finds that he got much right, though of course we have advanced beyond him.

One of the best chapters is on what we currently know about hominin evolution from the fossil record. Ethiopian paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie, in a volume bursting with outraged white academics eager to shriek “racism!” at Darwin, admirably acknowledges Darwin’s prescient genius: “As a paleoanthropologist of African origin … it gives me pride and honor to actually find ancient fossil remains of our ancestors on the continent where Darwin predicted they would be found.”

A Most Interesting Problem gives a fairly accurate depiction of what modern academia looks like on the question of the evolutionary history of Homo sapiens. There are still some dedicated scientists turning up fascinating and compelling evidence of our connection to the rest of the natural world. There are also many radical ideologues masquerading as scientists who are dedicated to overturning the scientific endeavor altogether in the interest of social justice millenarianism. These latter are multiplying at an alarming rate.

Those on the right who disdain Darwin and evolutionary theory should understand that the enemy of your enemy is not necessarily your friend. In any case, evolutionary theory is not altogether incompatible with religious belief. Among the evolutionary biologists who managed to reconcile their scientific convictions with their religious belief are Theodosius Dobzhansky and Francis Collins.

In a wonderful book, The Biology of Ultimate Concern (1969), Dobzhansky, an Orthodox Christian and one of the most important 20th century evolutionary biologists, invokes a strange pair: Dostoevsky and Darwin. He cites a line from The Brothers Karamazov expressing the incongruous miracle of the “vicious beast” man coming upon “the idea of the necessity of God.” Such a miracle is all the more startling given what Darwin showed us about the rise of modern humankind from still more primitive predecessors.

Yet, according to Dobzhansky, Darwin would perhaps have done better to alter the title of his second most well-known book. Instead of The Descent of Man, it should have been The Ascent of Man, which would have properly recognized our movement upward from a lowly state of incomprehension of sacred ideas to the well-developed spiritual capacities we now display.

Collins, author of The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief (2006), was another of those who argued for the compatibility between serious religious belief and the theory of natural selection. The two easily fit together inside the same mind without undue stress or damage to either belief. Darwinian evolutionary theory says nothing about the agency that might have set in process the living world that operates according to the logic of natural selection. And a great deal that we have learned about the shape of human life on earth from Darwinian theory is consistent with conservative Christian politics, from recognizing hierarchical orders to the strength of the bond between parent and child.

Let us all read Dobzhansky and Collins and others like them, so that the real scientists and the people of considered faith can close ranks against the most interesting derangement of “wokeism.”

Leave a Reply