If even a rough correspondence between poetic accomplishment and public reputation existed in America today, R.S. Gwynn would be one of our most widely read and highly honored poets. The publication of his selected poems, No Word of Farewell, would be an occasion for readers to measure the arc of a 30-year career. Today, however, when a shallow and self-serving creative-writing establishment doles out literary honors, a maverick like Gwynn remains largely neglected. Though widely published in journals and chapbooks, Gwynn has previously published only one full-length collection, The Drive-In (University of Missouri Press). Dana Gioia, in his introduction to Gwynn’s new book, ascribes the poet’s relative obscurity to this odd publication history but leaves unanswered why such a gifted poet has found it so difficult to publish in the first place. Now that Gwynn’s poetic output has been gathered into one attractive and easily attainable volume, perhaps this contemporary American master will at last find the audience he deserves.

Gwynn’s poetry exploits the full formal resources of English-language verse. A master of traditional forms and meters, Gwynn revels in difficult patterns and cunning rhymes. This classical rigor, combined with a mordant and irreverent wit, has led some critics to classify him as a satirist. But though he has written a number of delightfully wicked satires, Gwynn is a lyric poet of unusual depth and power, displaying a wide range of voices, subjects, and styles, in poems as remarkable for their deep feeling as for their formal restraint. What has perhaps misled critics is that, like all good satirists, Gwynn is a moralist. He skewers human pretensions and cruelty, yet treats suffering and weakness with tenderness and compassion.

A connoisseur and critic of American pop culture, Gwynn casts a cold eye on our society’s crass consumerist ethic. Sometimes the poet has only to dramatize our corporate mall morality to pillory it, as in “Local Initiative,” a poem about a family’s effort to commemorate their son’s death in a traffic accident:

For years they mailed petitions for a light

Or four-way stop; the city deemed it best

To table them until the time was right.

It took The Mall to honor their request.

You can’t take parents’ sorrow to the bank

But you can always bank on corporate needs.

Now like a docile river traffic flows

By fraying ribbons lost among the weeds,

And slowing to the changing light we thank

Blockbuster, Target, Texaco, and Lowes.

In “The Classroom at the Mall,” Gwynn exposes the moral and intellectual bankruptcy of pandering academic bureaucrats:

Our Dean of Something thought it would be good

For Learning (even better for P.R.)

To make the school “accessible to all”

And leased the bankrupt bookstore at the mall

A few steps from Poquito’s Mexican Food

And Chocolate Chips Aweigh. So here we are—

Gwynn’s sharp wit, keen sense of absurdity, and acute moral judgment are most evident in “Among Philistines,” which retells the biblical story of Samson and Delilah. Thanks to their fabled exploits, both characters have become famous in our celebrity-worshipping culture, but while Delilah revels in her cheap notoriety, Samson, in true heroic fashion, is disgusted to find himself among tasteless philistines who plaster his image on “The glossy covers of their magazines” and “ads for razors” with captions proclaiming “Hebrew Hunk Says We Shave Best!” Juxtaposing the crass diction of commercial advertising with stately biblical prose, the drama reaches its climax as Samson is led “through Gaza Mall / Past shoeshop, past boutique, Hallmark and Sears” uttering a prayer in which both levels of language mingle to comic effect:

Lord God of Hosts, whose name cannot be used

Promotion-wise, whose face shall not adorn

A cornflake box, whose trust I have abused:

Return that strength of which I have been shorn

That we might smite this tasteless shiksa land

With hemorrhoids and rats, with fire and sword. . . .

In lines like these, Gwynn’s wit can easily steal our attention from his remarkable lyricism. But in “Two Portraits” and “Human Nature,” his graceful treatment of human and natural subjects calls to mind Richard Wilbur and Robert Frost. In the three sonnets of “Body Bags,” Gwynn writes haunting elegies of local characters set in the Vietnam era. Though he skewers charlatans and hypocrites with savage derision, he evokes only compassion and sympathy for the world’s has-beens and losers. He can mingle dream and realism in haunting lyrics like “The Drive-In” and, in a suite of poems at the center of the volume, even write of his own first-person encounter with prostate cancer with dignity and grace. The poet’s brush with mortality produced both the brilliant monologue “Cléante to Elmire” and the sassy pastiche whose opening line startles with its echo of Jonson’s famous elegy: “Farewell, thou joy of my right hand, my toy.”

This rich and remarkably varied volume evokes only one small cavil. Sometimes the lighter poems draw out their jokes too far; one Shakespearean sonnet garbled in translation by ViaVoice is quite enough, thanks. What I remember about this remarkable collection, though, is the lyric grace of poems like “In Place of Elegy,” which incorporates even the trite language of a composition student killed in an auto accident into an elegy of stunning beauty and pathos.

With such a formidable record of accomplishment behind him, it is time R.S. Gwynn received his due.

Throughout the 19th century, American writers from Ralph Waldo Emerson to the lowest literary hack called for a poet to rise from our native soil and create poetry equal to America’s vast and varied landscape. With his second book, Very Far North, North Dakota native Timothy Murphy has answered the call, securing the title of laureate for at least one part of this continent-straddling nation. What Virgil was to the Italian peninsula or Homer to the Greek Mediterranean, Murphy is to the swatch of plains stretching from the Upper Midwest to the Rockies like a grassy inland sea. Surprisingly, though, Murphy evokes the stark and pallid colors of this sprawling region not in the long, unruly cadences of a Whitman or Sandburg but in lines as clipped and lapidary as a Roman epigrammatist’s.

A venture capitalist and farmer, Murphy exhibits none of the naive optimism of the literary boosters or self-proclaimed laureates of centuries past. Murphy’s West is not the Golden West of American myth-of land rushes and yeoman farmers dreaming of empire—but of the deserted plains and shattered hopes left in the wake of Manifest Destiny, where “returning bison, / gathering like a storm, / darken the bare horizon / of a land unfit to farm.”

A traditional poet in every sense of the word, Murphy possesses a classical temperament which comprehends tragedy and human suffering; he knows that “Care furrows the brow / and bows the straightest frame. / Thistles follow the plow, / and hail threshes the grain.” Spare and unadorned as a Dakota prairie, Murphy’s poems are generally short in line and length, metrically tight and artfully rhymed. They can evoke the solemn tones of a biblical psalm or the lucid brilliance of a Greek lyric. His verbal landscapes and portraits depict the lives and character of his local culture and region yet look beyond them to primal elements and patterns that predate human history:

Our Bronco bucked on rocks as daybreak’s glow

drove darkness down the range from summit snow.

We rode to where the switchback track was blocked;

and then we walked

into a world where strings were not yet strung

on tortoise shells, where Gilgamesh was young.

Haunted by rituals as old as human consciousness, Murphy’s poems mingle observations about farming, hiking, hunting, loving, and dying with allusions to Greek, Native American, and Norse myths. In writing of farming or hunting, he celebrates such ancient virtues as hard work, good husbandry, and expert marksmanship. Concluding his book with a group of poems on Chinese and Japanese history and art, he appears to have found—amidst North Dakota’s arid plains and buttes—the fabled Northwest Passage to the East.

Nowhere is Murphy’s allegiance to tradition more vividly seen than in his many poems about his literary and ancestral forbears. In “Red Like Him,” Murphy salutes his Yale mentor, Robert Penn Warren, whose advice to return to his roots is memorably recorded in “Collateral.” In “Horses for My Father,” Murphy pays moving tribute to the father who taught him to find his deepest relation to nature in stewardship. And in “The Steward,” Murphy combines this theme with another favorite, human and natural generation:

Morris no-till drills

pulled by three Versatiles

keep the soil from blowing

off his communal hills—

hills that the bison haunted

and his Sioux forebears hunted,

fields where the cocks are crowing

and his green sons growing.

As these lines attest, Timothy Murphy’s true home lies somewhere northwest of Robert Frost’s New Hampshire and Thomas Hardy’s Wessex, in a land where words endure like quartz.

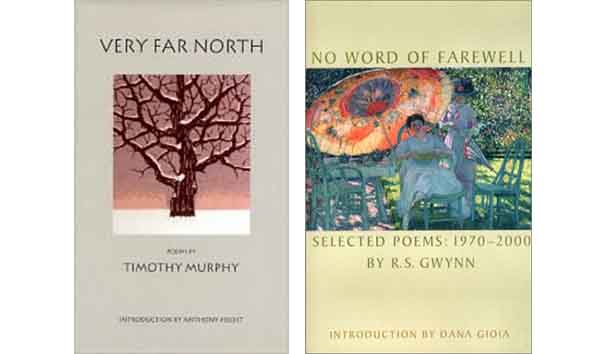

[No Word of Farewell: Selected Poems, 1970-2000, by R.S. Gwynn (Ashland, OR: Story Line Press) 167 pp., $16.95]

[Very Far North, by Timothy Murphy (London: The Waywiser Press) 108 pp., $18.95]

Leave a Reply