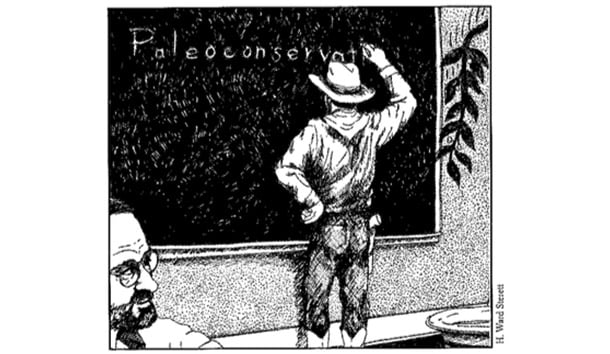

Paleoconservatism is the expression of rootedness: a sense of place and of history, a sense of self derived from forebears, kin, and culture—an identity that is both collective and personal. This identity is missing from the psychological and emotional makeup of leftists of every stripe—including “neoconservatives”—and is now disavowed by mainline conservatives of the Republican variety, seemingly bent on eradicating as much of the primeval stain as they can from their consciousnesses while apologizing for the faint discoloration that remains.

Identity—like patriotism and loyalty, among other things—is a problem for conservatives to the extent they see it at odds with the concept of Economic Man, for whom the term has no significance unless preceded by the word “brand.” For the left, the only valid human identity is economic status, which determines one’s political position in the context of the class war: Other identities (racial, ethnic, tribal, cultural, religious, national) are dangerous because they distract from all-important economic distinctions, and because they create enmity among groups who the dialectic has determined should be allies. The left, which (with the help of drugs and other deviant social behavior) in the 80’s created the crisis of homelessness, is and always has been homeless itself: men and women without a country, without a people, without a history—without God. But there is another reason why the left, especially in societies that retain so much as a vestige of their historic character, despises traditional identities. For leftists, these imply something enticing yet, for them, unattainable: a self-possession to be envied, a self-confidence to be resented, an assurance to be feared. What they perceive is not simply a threat to their political blueprint, to their vision of the future. It is an affront to themselves: their bogus identity, their false self-perception, their absurdly inflated sense of their own strength, most of which they owe to the bureaucratic institutions that protect their soft ineffectual selves the way a nautilus shelters a snail. This sense of affrontedness has produced a satanic hatred which, for the past 40 years, has been fueling a kind of public conspiracy—entirely unprecedented in the annals of history—whose end is the total deconstruction of a civilization by the elite responsible for its welfare and survival.

In this campaign of chaos and destruction, the chief and most effective tools have been the weakening of the Christian religion and Christian institutions, the promotion of multiculturalism—and virtually uncontrolled immigration from the Third World. Given their strong sense of identification with the American Republic as well as, in many cases, family trees rooted in the fertile abundant soil of colonial America, it was inevitable that it should have been the paleoconservatives who sounded the alarm over immigration and carried the anti-immigration battle to the enemy, whose response (entirely in character for it) has been name-calling from a safe distance rather than hand-to-hand fighting in the field, plus redoubled bureaucratic and propagandistic efforts beyond the sidelines. Given, also, the distraction of the general population by sports, sex, the internet, and a booming economy, the paleos seem to be losing most of the battles, and the war. The numbers of first-generation immigrants are approaching critical mass, while a Gallup poll taken during the last election season showed that a majority of Americans no longer believes that immigration to their country ought to be curtailed.

Such being the case, what should the paleoconservative response be? (Not the paleoconservative political response—there aren’t any genuine paleoconservatives in positions of real power—but the public, as well as the private, one.) My answers are either practically inutile, or else useful only in the long run. These are: pray; wait (“Catastrophe,” Ed Abbey thought, “is our only hope”); carry on as if nothing were happening; be strong.

Last fall, I received an academic calendar from my alma mater, The Trinity School in New York City. Having not paid a visit to 139 West 91st Street since my 20th reunion in 1985, I paged, astounded, through glossy four-color photographs depicting scenes from the daily life of the school. Gone were the awe-inspiring faculty, serious but not necessarily severe men in tweeds, dark suits, and rimless spectacles. Gone were the ranks of schoolboys uniformed in navy blue blazers, button-down shirts, striped ties, and oxfords (shoe-shine inspection promptly at 8:45 before Chapel, and an ear-tweak for the boy who’d forgotten to add his display handkerchief before leaving home that morning). Gone the straight rows of tablet armchairs, the teacher’s imposing desk, the youth in the corner holding his chair out in front of him by its hind legs and blubbering (the Trinity of my day wouldn’t have included him in a calendar, either). In their place were teachers dressed like college kids, coatless and tieless; students garbed as junior versions of their instructors; casual arrangements of tables to form mini-classrooms promoting fuzziness in feeling and in thought, hi addition to the Episcopal service (Trinity, founded in 1709, was originally the scholastic appendage of Trinity Church on Wall Street), there are now Jewish Chapel and Kwanza Chapel. The school, which shuts down for Rosh Hashanah and Kwanza as well as for Christmas and Easter, Martin Luther King, Jr., Day as well as Winter Vacation, etc., is apparently closed more than it is open to accommodate the sensibilities of a multicultural student body. The school went coed shortly after my graduation, and the incidence of non-Western faces has since greatly increased.

Flexibility in facing the vicissitudes of life is one thing, unlearning your upbringing another—a thing principled people wouldn’t do even if they could. Trinity School, having educated generations of students for life in the Old America, has—for the past 30 years—been cooperating enthusiastically in the work of destroying that America and displacing those it once trained to operate and inhabit it. All right: We are becoming strangers in our own country.

What to do? In addition to the foregoing list, I add several further suggestions. Be true to your forebears, and to the culture they created and—for nearly four centuries—sustained. Wear a coat and necktie in polite society, even on an airplane. Speak out! Make yourself heard as loud and as strong as your lungs, and the co-opted press and electronic frequencies, permit. Keep your sense of humor, ALWAYS…. Go to Church.

Leave a Reply