The journalist Peter Hitchens is a familiar figure in the British media. For several decades, his newspaper columns, first in the Daily Express and now in the Mail on Sunday, have bemoaned the state of modern Britain. Hitchens has written at least 10 books of which easily the most famous is his first, The Abolition of Britain, published in 1999.

A quarter century has passed since then. The 25th anniversary of the book’s publication coincided with the beginning of the Southport riots over issues relating to immigration and crime and fell less than a month after the coming to power of Keir Starmer’s Labour government. As Abolition was written in the early years of the Blair government and partly in response to that government’s policies, now is a good moment to look back on Hitchens’ book, the issues he raised, and how things have developed in the years since.

Hitchens saw Tony Blair’s New Labour government as the end of a long revolution beginning in the 1960s that had dramatically affected Britain’s identity, religion, morality, popular culture, and education system, and which led to the decimation of her towns and cities. At the opening of the book, Hitchens expressed the opinion that there was “a convincing reason to believe that the Tories will never again hold power in Britain.”

An uninitiated observer reading this in 2025 might say this is ridiculous, since the Tories have held power for most of the last 15 years. That is true, but they only did so as a sort of adjunct or footnote to New Labour. Former prime minister David Cameron famously described himself as the “heir to Blair.” Another former Tory leader, Liz Truss, gave a very revealing interview to Connor Tomlinson of the Lotus Eaters podcast, where she spoke of Blair’s “untoward influence on the Conservative Party.” “There are too many people in the Conservative Party who say Blair is the master and we should admire Blair and we want to be the heirs to Blair,” she said.

While in power, the Conservative Party did nothing to overturn the Blair revolution; rather, it strengthened and advanced it to new heights.

I first read Abolition around 2000 and recently reread it for the first time in many years. Although the problems Hitchens discussed then are now far more advanced, the book brilliantly sets the scene for our current malaise. Many paragraphs eloquently describe what has happened to Britain in the last 60 years. For example:

We allowed our patriotism to be turned into a joke, wise sexual restraint to be mocked as prudery, our families to be defamed as nests of violence, loathing and abuse, our literature to be tossed aside like so much garbage, and our church turned into a department of the Social Security system…

We tore up every familiar thing in our landscape … demolished the hearts of hundreds of handsome towns and cities, and in the meantime we castrated our criminal law, because we no longer knew what was right and what was wrong, and withdrew our police from the streets of the suburban wilderness we had made…

The most significant change for the great majority is that life is no longer so safe, so polite or so gentle as it once was.

A large section of the book discusses issues relating to morals, the family, and education. No fewer than five chapters deal with moral questions, including the massive increase in illegitimate births, the undermining of marriage, the rise of divorce, and changes in attitudes towards homosexuality.

Hitchens recorded how Britain went from having one of the lowest rates of illegitimate births in the Western world to out-of-wedlock births becoming a very common phenomenon. Hitchens summed up the situation and its consequences thus:

Marriage has collapsed in Britain… while illegitimacy—the very thing marriage is supposed to prevent—has become so common as to be the norm. Shame and stigma, which once both defended respectable marriage and heaped misery on the poor bastard and his wretched mother, have disappeared. Instead, there is the slower, vaguer, more indirect misery of a society where fewer and fewer children have two parents, where more and more women are married to the state.

Hitchens charted the evolution of an organization called The National Council for the Unmarried Mother and Her Child, which originally wanted to reduce illegitimacy but ended up calling for acceptance of it. It subtly manipulated language so that terms such as “illegitimate child” and “unmarried mother” fell out of use and were replaced by “one-parent family.” Hitchens called the acceptance of illegitimacy and cohabitation “the single greatest blow to the ideal of marriage.”

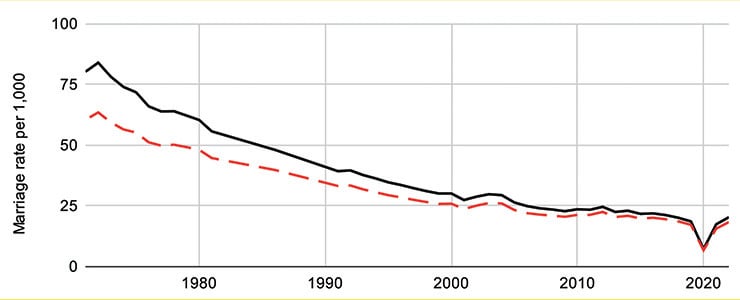

(Office of National Statistics)

Nonetheless, when Hitchens wrote his book in 1999, illegitimate births were still the minority. By 2021, the majority of British births were illegitimate, according to the UK Office for National Statistics. Similarly, cohabitation has increased by 144 percent in the time since Abolition was published, according to a House of Commons report. The Centre for Social Justice estimated in 2013 that as many as 85 percent of British couples cohabit at some point in their relationship.

Hitchens also commented on the rise of divorce, particularly taking into account the great liberalization of the 1969 Divorce Reform Act, which massively expanded the grounds for divorce, previously only available in cases of adultery, cruelty, and other extreme circumstances, by allowing divorce under the very broad grounds encompassed in the term “irretrievable breakdown.” Since Abolition was published, however, British divorce law has become even more permissive. The 1969 Act kept the concept of “fault,” but in 2020 the Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act for the first time created “no fault” divorce, which by then was standard in America.

In Abolition, Hitchens quoted a 1982 article by the British legal scholar Brenda Hoggett that “we should be considering whether the legal institution of marriage continues to serve any useful purpose.” In 2017, Hoggett, now known as Lady Hale, was appointed president of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom.

Hitchens chronicled the rise of what was then generally known as the homosexual agenda, but which has now expanded to include a range of sexualities and gender identities and an ever-increasing alphabet soup, now often called LGBTQ. Abolition was written just as this movement was advancing from the fringe into the mainstream, with several openly gay ministers serving in the Blair government.

In the 2000s and 2010s, the LGBTQ movement became one of the most powerful lobby groups in the UK, with marriage being redefined in order to include same-sex couples and these couples also being given the right to adopt children. The LGBTQ activist group Stonewall acted almost as a branch of the government in the 2010s, with government departments competing to make its list of the most LGBTQ-friendly workplaces. This lobby group still wields considerable influence over corporations, universities, and schools, though its aggressive promotion of transgender ideology has caused its star to wane somewhat, and many government agencies have withdrawn from its programs.

Nonetheless, the damage done to children by exposure to LGBTQ ideology is incalculable. Some years ago, gay activist teacher Andrew Moffat proudly boasted that thanks to his efforts, every five-year-old is now aware of the existence of same-sex relationships.

Sex education has become even more explicit today than Hitchens described it in Abolition. In 1999, it was not a mandatory subject and parents had an absolute right to withdraw their children from sex education classes. However, under the Children and Social Work Act 2017, which contained provisions on sex education that came into force in 2020, “Relationships and Sex Education” was established as a compulsory subject in British secondary schools. Parents must now ask permission from the school to withdraw their kids from sex education, and they cannot even make the request after the child turns 15.

Four chapters in Abolition deal with the subject of education, especially on teaching history and English. Of the teaching and knowledge of history, Hitchens wrote:

The lore of our tribe, the stories of our ancestors, the memories which our parents held in common, have simply ceased to be. Thirty or forty years ago, we might have all known the stories of Alfred and the cakes, of Canute and the waves, of Caractacus and Boadicea… The titles of the parables—the Sower, the Prodigal Son, the Talents—would have instantly conjured up a picture in the rich colours of a stained-glass window… Now these things are as meaningless to millions as the forgotten myths of ancient Greece.

Hitchens noted that the once-popular 1930 comic history book 1066 and All That would be incomprehensible to young people in Britain today since not knowing the history they could not understand the humor.

Hitchens chronicled the influence of long-forgotten left-wing educational revolutionaries, such as E. H. Dance, A. K. Dickinson, and P. J. Lee, who practiced a “ruthless rejection of all the old history.” Dickinson and Lee complained that the old-fashioned methods of teaching history had “two very undesirable characteristics,” which were “concentrating excessively on introducing pupils to the national heritage” and “treating history as a body of received information to be accepted and memorized.” The new history they taught moved away from a focus on achievement and heroism to one on suffering and deprivation.

Hitchens described how the old O-Level (ordinary level) British school qualification was a neutral test of knowledge, while the new GCSE that replaced the O-Level in the 1980s was specifically designed to be “non-discriminatory.”

In more recent years, “non-discriminatory” history has been succeeded by “woke history,” which forces British school children to endure such American imports as Black History Month and Pride Month.

Along with undermining the teaching of history, undermining the teaching of English was essential to separating the British people from their roots. Hitchens described the domination of written and spoken English as “one of Britain’s most powerful bastions.” He outlined the role played by the National Association for the Teaching of English (NATE) in radicalizing the English curriculum. One of NATE’s leading voices was London University Professor Gunther Kress, who wrote in 1995:

English is a carrier of definitions of culture… English is a carrier of definitions of its society… The subject English is the only site in the curriculum where all modes and media of public communication can be debated, analysed and taught. There is nowhere else… English is the site of the development of the individual in the moral, ethical, public, social sense.

Kress proposed that texts should be selected to communicate “socially and culturally crucial values.” Hitchens suggested that Kress’s most crucial value was what is now called “multiculturalism.” He quoted Kress as asking, “What kind of English curriculum can prepare children to be productively intercultural and polycultural… rather than passively, anxiously or angrily monocultural?”

And so, the English classics must be replaced by those of lesser writers so children can become “intercultural.”

The English literature curriculum of the 1950s included, among others, Chaucer, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Bacon, Milton, Bunyan, Swift, Gibbon, Defoe, Wordsworth, Hardy, and Shaw. While writers like Shakespeare and Chaucer still feature, they are now frequently accompanied by African American female writers such as Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou or by instantly forgettable novels only selected because they contain politically correct messages about race and gender.

Now, however, there are those among our political establishment for whom even Shakespeare and Chaucer are suspect. In 2023, Shakespeare’s complete works, along with Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Milton’s Paradise Lost, were flagged by the government’s “Prevent” counterterrorism strategy as “key texts” for “white nationalists/supremacists.”

If the decline in education, morality, religion, and other aspects of the culture is amply covered in Abolition, there is one significant issue that Hitchens almost entirely ignored: mass immigration. A new edition of Abolition published in 2018 contains a new afterword in which Hitchens stated that he “deliberately did not include” immigration as an issue in the original edition.

Yet it is this phenomenon, perhaps more than any other, that has changed the face of modern Britain. Lonely prophets such as Enoch Powell outlined the threat of immigration in the 1960s, but few listened. Hitchens continues to regard Powell’s 1968 warning as distasteful, even though it has been thoroughly vindicated.

In the time since Abolition was published, the issue has reached boiling point. The increase in Islamic terror attacks, the grooming gang scandal involving Pakistani Muslim men grooming and raping white British girls, the illegal channel crossings (over 150,000 since 2018, according to Migration Watch UK), and the recent stabbings of children by the son of Rwandan “asylum seekers” have all no doubt contributed to lighting the spark that caused the riots in northern England in the summer of 2024. None of this had happened yet in 1999, yet British discontent over Third World immigration goes back to at least the 1950s. Hitchen’s omission of the topic from Abolition is certainly a serious flaw.

The immigration issue aside, The Abolition of Britain still stands out as an excellent analysis of all that has gone wrong in Britain during the last 60 years. It deserves to be read and studied for many years to come.

Leave a Reply