Like many young men graduating high school in 1966, my father took a fast track to the politically seething, war-shattered jungles of a small country on the other side of the world. He had no middle name, no college degree (nor any aspirations of pursuing one), five siblings, and no “rich dad” culture to be passed down to him by my brick-and-mortar granddaddy. My father may have shared a high-school alma mater with Elvis, but there were no sprawling Graceland campuses waiting in the working-class neighborhoods of north Memphis. Uncle Sam wanted Dad. Uncle Sam got him. The young lieutenant received his commission, married his high-school sweetheart, and took his crew cut, his better than 20/20 vision, and his trust in General Westmoreland to Vietnam.

My dad was not drafted. He volunteered for the United States Army. He did two tours in-country, was a crack shot, and came home with the kinds of medals and commendations a son brags about to his friends. His medals, plaques, and citations sit on the shelves of his memorial at the end of a hallway in my home, beneath the framed flag that covered his casket. I still brag about him to my friends. The relationship between father and son can be one of the greatest blessings provided by the Lord, and I am grateful I gradually became my dad’s confidant regarding many things, including his time as a combat officer.

In my late teens, my dad and I began to talk about his experience in Vietnam. He had long found it difficult to articulate his memories and the sense of pride mixed with terrible loss and confusion that defined so many of the American combatants from that period. As I began to move into manhood, he and I had the opportunity to work together for several years—much of that time on the road in the cab of a mover’s truck. His recollections came randomly, began and ended abruptly, and never failed to give me insight into the man who gave me life. As we drove past endless mile markers, I grew to know my father in a new light. He seemed to have lived in a world different from all the documentaries and movies I had seen about the late 60’s and early 70’s. There were no stories about drug culture, campus protests, psychedelic music, and swingers’ clubs. Dad’s memories of that time were all olive drab and camouflage. There were stories about home and loss. I was born while he was away on his second tour and after he had a close friend shot from the sky in an Army helicopter, two events he told me changed his life forever.

Not long after one of these conversations about friends and family, my dad and I shared a moment that would change my life, too.

Late in 1989, I took advantage of an open weekend and went to a movie. Born on the Fourth of July is an account of the life of Ron Kovic, a U.S. Marine who was shot and partially paralyzed in Vietnam. Tom Cruise played the title role. I am no film critic, and I am not always sure why I consider a movie “good” as opposed to “bad.” I tend to put films into four categories: those I want to own after I have seen them; those I think about; those I enjoy; and those that make me wish I had spent my money elsewhere.

That year, I’d done quite a bit of thinking about Born on the Fourth of July.

My father did not watch movies or read books about Vietnam. This was likely because of the mental and emotional trauma he experienced during his time in the jungles and rice paddies. He had no problem watching the war movies he had grown up seeing—those depicting World War II or the War Between the States. Yet he simply could make no place in his life for those that either vilified or glamorized the war he had helped fight. “I was in-country twice,” he once told me. “I saw enough.”

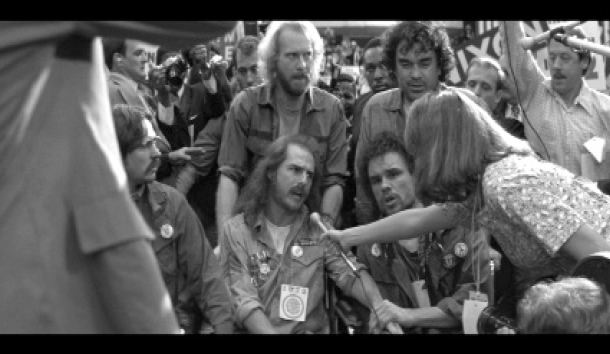

At 19, I was well aware that I was spending most of my days three feet away from a living connection to one of the most disputed military conflicts in modern history. The stereotypes of the era were familiar to me—dope-smoking guitar strummers carrying flowers to protests, shirtless grunts sitting on sandbags between patrols, dull color footage of F4 Phantoms streaking over the dense jungle canopy, politicians perfecting the jargon of misinformation. I wanted inside information. What did my father, who had lived through all of this, think of those stereotypes? What was the real story, particularly about those who had been belligerents for peace?

I took my opportunity during a lunch break, and I asked my dad what he thought about the purpose of the war. I told him I had seen the movie about Kovic, and I asked him what he believed he (and thousands of others) had been sent there to do. And I asked him what he had felt upon seeing the opposition, in whatever form, when he returned home.

In a moment of rare total openness, Dad spoke for a while on his changing perspectives about the cause and waging of the war in Vietnam. Politics, history, tactics—everything was on the table.

“I don’t like to say hate, but I hate Jane Fonda,” he began.

On the whole, my dad was a gentle man. Six feet tall and all of 250 pounds, he was more likely to be found wrestling with his children in the living room than confronting anyone about anything. I am not sure I’d ever heard him use the word hate before that day, but I got the gist in a hurry.

“She should be in jail, not on TV.”

Fonda’s actions had burned a path of disdain through my father’s conscience, and that trail of anger was still fresh. “I never really had any personal problem with any hippies,” he continued. “Just one time some guy shot his mouth off in a 7-11, but I just told him to mind his own business, and that was about it. They didn’t know what they were talking about. They sure did cause a lot of pain for a lot of other guys, though. That is the part that makes me angry.”

I was getting what I thought I wanted from my dad. What followed, then, was unexpected.

“But, you know, this movie that is out now, that doesn’t bother me at all.”

I was shocked, and, for a moment, I even thought about correcting him. He had not seen Born on the Fourth of July and never would, but those who have know that it depicts the Vietnam War as a disaster of epic proportions. That may indeed be the truth, but I was certain that it would be difficult to feel that way if your blood and the blood of your friends had been left on the jungle floor.

I didn’t want to lose the moment, but I had to know why the movie didn’t bother him.

“That guy earned his protest. He can hate every single thing about it, or he can love it if he wants to. He has that right. He went through it.”

If you have earned the right to comment, you may comment. If you have not earned it, keep your mouth shut.

Back then, I was a son in his late teens, looking to feed a curious mind with real-life historical information so I could, in future days, wax eloquent about an event in which I had not participated. My father offered a perspective that would serve me in all the events I actually would experience.

Now I am halfway through my 40’s, a father of six children. I am a coach and a teacher who has had the privilege of working with hundreds of students over the last 20 years. My field is theology, and I am often formally or informally sought for counsel. It comes with the territory. My work means I am almost constantly critiquing a society that increasingly hates itself and its own foundation. The topics are endless, and yet they are all the same. After an adult lifetime of growing, learning, teaching, and sharing it is still impossible for me to outdo the wisdom I was offered by a middle-aged truck driver who had seen life up close and had learned some of its lessons. If you have not been through something, be careful with your criticisms of those who have. Maybe you can keep your opinion to yourself. Inexperience is not a great source of information or perspective.

If you are not willing to step into the fire and go through something firsthand—if you are unable to bring yourself to walk that famous mile in another’s shoes—perhaps you should be more considerate of those who were willing to step forward. A man in harm’s way on the battlefield, a teacher in the dynamically flawed environment of the classroom, a parent in a dying and hostile society, a caregiver for someone on the rough end of a medical diagnosis—do not presume to have the right to speak in scathing tones or with acceptable criticism if you have not stood eye to eye with such struggles.

I have no qualms about critiquing things that need to be critiqued or even standing in open opposition to those things that need to be opposed. I, too, have a combative calling—but I deal in words and texts, not guns and tripwires. But I hesitate to offer commentary if I have not earned the right to speak. Criticism demands a willingness to accept accountability in kind. Words without this kind of backing are little more than wasted air.

Today, too many are willing to hurl abuse from the shelter of anonymity, the battlefields of our virtual worlds. We are unproved, free of scars, and yet happy to make sure the world gets a full clip of our opinion. Experience is ugly and may even involve failure. We would rather not go to that much trouble.

How much of our rancor and mindless barking would disappear if we really thought it were necessary actually to be qualified to speak?

There is a word for the kind of wisdom that comes from ignorance and inactivity: Foolishness.

I got that from a good source.

Leave a Reply