Too many conservatives get Thomas Hobbes wrong. In a recent piece for The Imaginative Conservative, Bradley Birzer argues that the famed 17th century English philosopher is responsible for supplying the recipe for “a collectivist horror.”

He credits Hobbes with having “inspired countless tyrants,” and says that “his collectivist nightmare…is not just the stuff of George Orwell[’s] and C.S. Lewis’s dystopias, but the basis of real-life hellholes, such as those found in twentieth-century Germany, Russia, and Cambodia.”

Others in the contemporary conservative movement have taken Birzer’s position. Nationally syndicated talk radio host, author, and Fox News personality Mark Levin, for one, largely agrees with him in seeing Hobbes as a source of mischief. In his 2012 book Ameritopia: The Unmaking of America, Levin rails against the dangerous “restrictiveness” of Hobbes’ vision of individual freedom.

These conservatives are mistaken, embarrassingly and scandalously so.

This is not merely a theoretical concern. Getting Hobbes correct can help us acquire a deeper appreciation for, and understanding of, our present circumstances. The politics of crisis that have been the lifeblood of American political life and, more generally, European politics for much of Western history, has been on steroids during the last few months.

If Hobbes is the champion of individuality that I contend he is, then he has something important to say to us about our present circumstances. Americans across the political spectrum have an ever-growing sense that their government is not the impartial custodian of law it is supposed to be. That could vindicate Hobbes’ contention that where there is a collapse of faith in the sovereign, there is a return to the state of nature: a condition of war.

In light of the especially intense and extraordinarily unusual election year upon us, this increasing sense of alienation from government is forcing more and more Americans to endorse a proto-Hobbesian reading of the current situation, whether they have ever heard of Hobbes or not.

Far from being a collectivist, Hobbes was fundamentally an individualist and has been recognized as such by major political theorists including Michael Oakeshott, Ferdinand Tönnies, and the Canadian Marxist scholar C. B. Macpherson. It was Macpherson who properly identified Hobbes, along with John Locke, as “a father of possessive individualism.”

Hobbes assigns ontological primacy to the individual. He preceded that strain of European liberalism emphasizing individual autonomy and gratification. While individuality came into its own at least partly by way of Christian personalism, and while philosophers of the 14th century left us with the isolated individual who lives in fear of violent death, it was Hobbes in the middle of the 17th century who pushed these concepts further.

Hobbes’ study of man’s life in the absence of political order as being “nasty, brutish, and short” became part of our Western consciousness. This was especially so after the publication of his magnum opus, Leviathan (1651), written in exile during the English Civil War and at the beginning of Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth.

Hobbes capitalized on the intensifying impulse toward secularization and the emergence of the nation-state by postulating the individual as the most basic of metaphysical and, thus, political units. Civil society from his perspective was a collection of mutually suspicious individuals who needed authority to protect them and their natural right to life.

From there it was a hop, skip, and jump to Locke and a fully developed theory of liberalism, based on each person’s natural rights to life, liberty, and property.

In his magisterial introduction to the 1946 edition of Leviathan, Michael Oakeshott identifies Hobbes as an emblematic proponent of what he calls “the morality of individuality.” Oakeshott contrasts this with an older morality of communal ties and, tellingly, the morality of the collective.

Within the framework of the morality of individuality, humans are self-referential beings who engage in self-chosen pursuits. Moreover, they enjoy making choices for themselves. Unhappily, these engagements lead to collisions between individuals. For the sake of mitigating this situation while maximizing the range of individual opportunities, sovereign governments exist.

It’s true, of course, that Hobbes argued on behalf of an authoritarian government. But this was because of three distinct, yet conceptually related, reasons:

First, the concept of sovereignty, understood as a sovereign actor, requires someone who exercises authority. What this means is that a sovereign actor is the repository of all authority, for it is as logically impossible for a sovereign being to possess partial authority as it is for a woman to be somewhat pregnant.

Second, a government is, by definition, the locus of authority for all who fall within its jurisdiction. The term “sovereign government” is thus redundant, just as a “lawless government” is meaningless in the Hobbesian view, insofar as it is a contradiction in terms.

Third, the only alternative to accepting the necessity of government is anarchism. Since Hobbes was not an anarchist, he affirmed the need for government, i.e., a sovereign. According to Hobbes, it was anarchy that prevailed in the state of nature, from which those who accept civil society escape. It is in order to avoid anarchy that those who contract to live under governments are acting as they do. Any division of sovereignty in the arrangement created might have the effect of bringing back the warfare that existed in the state of nature.

So Hobbes was for an authoritarian government, but only one that was more, not less, amenable to the ontological and moral individualism he affirmed. For Hobbes, the sovereign governs through laws that unite all subjects of a state as parts of an association. These laws are, as Oakeshott accurately described them, “non-instrumental rules” or “adverbial conditions.” What this means is that, far from being what we’d expect from a collectivist government, the laws of Hobbes’ sovereign do not specify any actions that subjects need to perform. They do not tell people what to do. Rather, they tell people how to do whatever it is they choose to do.

Even this description may not do justice to the extent of Hobbes’ individualism. To Hobbes, laws prescribe ways through which subjects may consider pursuing their own self-chosen actions. For example, there are all sorts of ways one could choose to support one’s family. Hobbes’ concept of law does not require individuals to opt for any of these paths specifically. Yet it does forbid them from choosing any course of action that involves stealing from others.

In Hobbes’ vision, the social order has no telos. There is no overarching end, no single substantive collective goal toward the realization of which individual members are required to contribute. Hobbes is not interested in “social justice” nor in collective virtue. Sovereignty and authority exist in his theory for two overriding reasons: to preserve tranquility and for the “pursuit of commodious living.”

For anyone who may still doubt Hobbes’ commitment to individualism, two further points can be made.

First, no one to my knowledge who has attempted to draw a line between Hobbes and the architects of any 20th century totalitarian regime has supplied any evidence to substantiate their contention. If Hobbes has inspired countless tyrants, as Birzer asserts, one would think there would be at least one tyrant somewhere who identified Hobbes as the inspiration for his regime.

Second, although there are aspects of Hobbes’ political thought that could be conscripted for tyrannical ends, the same might be said of many other political thinkers. This is certainly true of those who have promoted natural or human rights, democracy, equality, and social justice.

Indeed, it was the Enlightenment philosophy of “the Rights of Man” that was invoked to justify the carnage of the French Revolution. Such was the blood and gore committed in the name of this egalitarian dogma that Edmund Burke (whom Bradley Birzer professes to admire) felt compelled to compose an unqualified repudiation of all human rights doctrines.

Examining all the arguments collectively, Thomas Hobbes was conclusively an individualist. Rather than pointing toward Hobbes as the progenitor of today’s authoritarian cultural revolutionists, conservatives might find more deserving culprits.

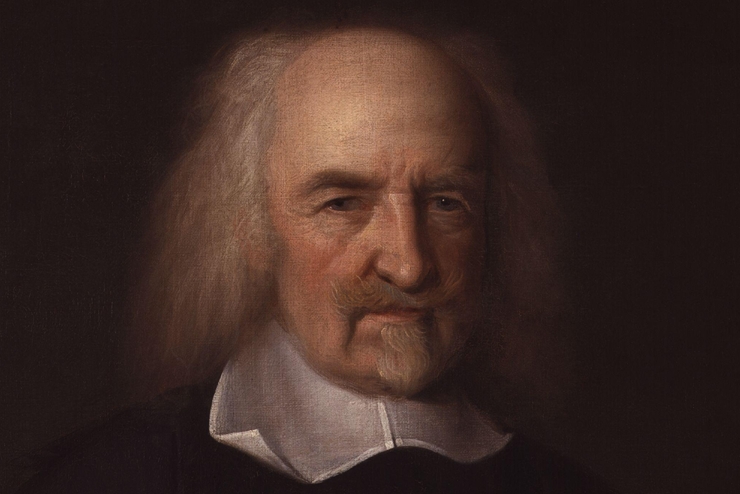

Image Credit:

above: Thomas Hobbes, oil on canvas, by John Michael Wright c. 1669-1670 (National Portrait Gallery/public domain)

Leave a Reply