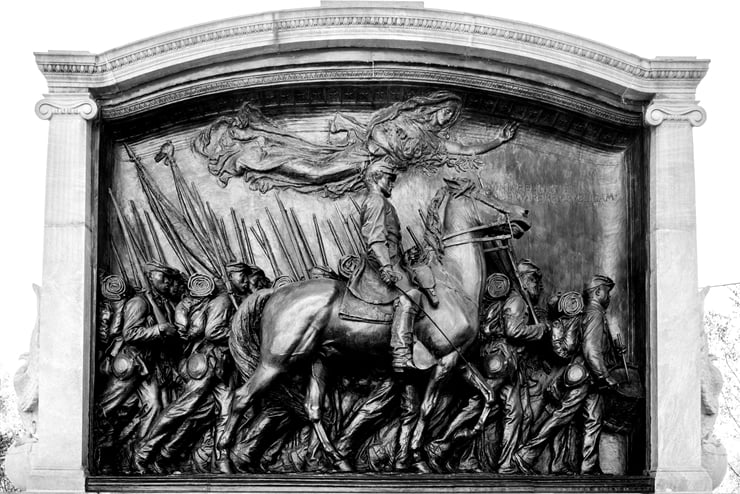

A few days ago, rioters in Boston defaced the Robert Shaw Memorial, a masterpiece in high relief wrought by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whom I consider to be, alongside Frederic Remington, the most distinctly American of our sculptors. I am supposing that the attack on the memorial was no mere act of vandalism, no instance of “rioting mainly for fun and profit,” as Edward Banfield called it in The Unheavenly City, but a real expression of political hatred. If I am wrong about that, I could turn elsewhere for instances: churches set afire, harmless businesses smashed, men of good will slandered, all in the name of justice.

For most of us, such acts of hatred and senseless destruction may seem incomprehensible. The key to understanding them is a motive that Friedrich Nietzsche first identified in his On the Genealogy of Morals (1887), and that Max Scheler, refining and correcting Nietzsche’s insight, made the subject of a brilliant book: Ressentiment (1913).

For most of us, such acts of hatred and senseless destruction may seem incomprehensible. The key to understanding them is a motive that Friedrich Nietzsche first identified in his On the Genealogy of Morals (1887), and that Max Scheler, refining and correcting Nietzsche’s insight, made the subject of a brilliant book: Ressentiment (1913).

The French term is necessary because we are not talking about mere resentment. A neighbor who takes advantage of your good nature by letting his dog run loose in your yard is annoying, and the act may stir up passing resentment. But ressentiment, says Scheler, “is a self-poisoning of the mind,” a consequence of repressing otherwise natural but negative emotions, leading to “certain kinds of value delusions and corresponding value judgments. The emotions primarily concerned are vengefulness, hatred, malice, envy, the impulse to detract, and spite.” It goes beyond these evils and creates in the soul an inversion of values, so that the afflicted soul will say that the good it cannot enjoy is actually evil, and that the evil it indulges is good.

It is important to note that the emotions Scheler lists are but stages on the way to ressentiment. Take the desire for revenge. If you give me a box on the ear and I give you one right back, we clear the air, and ressentiment has no food to feed upon. Soldiers, says Scheler, are least subject to ressentiment. Think of Civil War generals Grant and Lee at Appomattox, or of William Sherman’s gracious and generous treatment of the Confederate soldiers in the command of Nathan Bedford Forrest, causing those two men to become fast friends.

It is important to note that the emotions Scheler lists are but stages on the way to ressentiment. Take the desire for revenge. If you give me a box on the ear and I give you one right back, we clear the air, and ressentiment has no food to feed upon. Soldiers, says Scheler, are least subject to ressentiment. Think of Civil War generals Grant and Lee at Appomattox, or of William Sherman’s gracious and generous treatment of the Confederate soldiers in the command of Nathan Bedford Forrest, causing those two men to become fast friends.

An act of vengeance is not the same as vindictiveness, whereby you seek occasion to attack, for “great touchiness is indeed a symptom of a vengeful character,” as you “tend to see injurious intentions in all kinds of perfectly innocent actions and remarks of others.” Triggered! Thaddeus Stevens, the club-footed real estate mogul who never could have fought in the Civil War, was vindictive; Sherman was not, and he suffered politically because of it.

Or take envy, the only one of the seven deadly sins that brings not even a phantasm of delight. Here we are on dangerous ground. An emulous actor may cease to feel envy once success comes his way. He does not yet say that it is wrong to recognize excellence; he just wants his own to be recognized. To that end, though, he may indulge his appetite for detraction, “to disparage and to smash pedestals, to dwell on the negative aspects of excellent men and things.”

Likewise, the feminist is glad to believe the slanderous tale that her grandfather beat her grandmother. She is disappointed to learn the truth, that he was a modest and kindly man after all; but no matter, she who seeks for bad men to hate will find plenty. Or she need not find specific men at all, when she can settle upon a vague “patriarchy.” The less specific and personal is the object of hatred, the closer we come to ressentiment.

These evils in a man sour and ferment into ressentiment when his felt inferiority is perceived as inevitable, as a destiny built into the nature of the world or of his society, against which he is impotent. He wants to strike back but he cannot. Or, the woman wants to tower over the man but she cannot. Both want history itself to be otherwise, but it cannot be. Then, says Scheler:

the oppressive sense of inferiority…cannot lead to active behavior. Yet the painful tension demands relief. This is afforded by the specific value delusion of ressentiment. To relieve the tension, the common man seeks a feeling of superiority or equality, and he attains his purpose by an illusory devaluation of the other man’s qualities or by a specific ‘blindness’ to these qualities. But secondly—and here lies the main achievement of ressentiment—he falsifies the values themselves which could bestow excellence on any possible objects of comparison.

The fox in the fable who cannot reach the grapes calls them sour. That is detraction. The dog in the fable cannot eat the hay in the manger, so he makes sure the cow will not either. That is spite. But the fox has not gone so far as to prefer sour grapes. The dog has not gone so far as to prefer starvation. The man of ressentiment does go so far. Examples in our time are easy to find, including those that bear upon the current riots. Young black students who with the encouragement of their peers might succeed in school are sneered at for “acting white.” The courtly and earthy friendliness of blacks in the rural south is sneered at, too, as if it were no more than cringing; and thus do those of ressentiment reveal their own cowardice, like that of Uriah Heep.

Similarly, women are encouraged to look at the accomplishments of men before our time as if they were insults or encroachments upon their liberty, as if women and not men would have built the Brooklyn Bridge if they had been given the chance.

Ressentiment is, if I may indulge an oxymoron, gigantically petty. It is Jesse Jackson and the students of Stanford, chanting, “Hey hey, ho ho, Western Civ has got to go.” I saw the same phenomenon at Providence College, where I taught for 27 years. The opponents of its Western Civilization program did not want to read the Tao Te Ching alongside the Psalms, or the Bhagavad-Gita alongside the book of Genesis. They refused to see that the best preparation for studying a civilization wholly alien to yours would be to study your own origins that had, over the chances and changes of millennia, become largely alien to you.

No, they were not interested in that: They had no stake in it. Nor could I appeal to the greatness and vast variety of what we had put before them, covering four or five disciplines, a dozen or more cultures, and 3,000 to 4,000 years. The very greatness itself was the offense.

“Still European,” said the bitter freshman from Colombia, when I told him we were going to read Pedro Calderón, the greatest playwright in his own native language. Where else but in school itself would he have learned his lesson in ressentiment? Puny teachers do not revel in the greatness of John Milton or Alexander Pope or Charles Dickens. The greatness of such artists is an affront, ostensibly because they did not believe the values we happen to assert today—but actually because they existed and were what they were. Had the blind visionary who composed Paradise Lost been second-rate, he could be forgiven.

That is what galls. For the man of ressentiment still senses the truth even though he cannot speak it openly. Milton is instructive here. Satan does not think that Adam and Eve are paltry. He knows they are noble. He does not think that the earth is a mere speck of mud. He knows it is beautiful:

The more I see

Pleasures about me, so much more I feel

Torment within me, as from the

hateful siegeOf contraries: all good to me becomes

Bane, and in Heaven much worse

would be my state.

That is why he wants to destroy it. Think of an old embittered woman snickering to see a couple about to be married, predicting—wishing—their unhappiness. Think of gay men looking at the same couple and dismissing them as “breeders.” Think of the hatred once aimed at the Boy Scouts prior to their shameful retreat. People hated them not despite their helping boys to become normal and healthy men. They hated them because of it.

Hence we arrive at the attack on the Shaw Memorial. In 1863, Robert Shaw died a hero’s death at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner near Charleston harbor. He was a 25-year-old white man, a colonel, leading the Union army’s first regiment of Negro soldiers. The Confederate general in charge of the fort, Johnson Hagood, in an act of remarkable gracelessness, ordered that Shaw’s body be interred in a mass grave with “his niggers.”

Hence we arrive at the attack on the Shaw Memorial. In 1863, Robert Shaw died a hero’s death at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner near Charleston harbor. He was a 25-year-old white man, a colonel, leading the Union army’s first regiment of Negro soldiers. The Confederate general in charge of the fort, Johnson Hagood, in an act of remarkable gracelessness, ordered that Shaw’s body be interred in a mass grave with “his niggers.”

The memorial in Boston, then, was for a young man who gave his life for the sake of the noble black men he proudly led. He is depicted on horseback, with the black men before and behind him; and Saint-Gaudens sculpted them with great attention to age and to individual personality.

Why would the rioters want to deface that memorial? That is like asking why the man of ressentiment does not want to receive a gift from someone he hates. Feminists can condescend to “forgive” weak and ineffectual men. They cannot forgive strong and effectual men. It does not matter that Shaw was a fierce opponent of slavery. The point is that he was giving of himself, from his strength, and those who feel themselves to be inferior cannot abide it.

Students who protested at my old school were not grateful for being given a rare chance to study great authors and artists with teachers who knew their works and loved them. They did not want the education that W. E. B. DuBois himself would have recommended to them. They did not say, “Thank you for bringing Homer before our eyes! May we also have the Rig Veda?” The greatness was the offense.

The noblest man, the man most free in his spirit, rejoices in the nobility of his enemy. It is not pride, but a free acknowledgment of a real value that exists apart from the persons involved. What matters is not whether I am Michelangelo, but that there should be a Michelangelo at all. For I derive my worth directly from the world of objective values, and not by comparison with others.

As long as we are interested in making manifest the highest of these values, says Scheler, “the question who realizes them will be of secondary importance, although each individual will be intent on doing it.” A saint cannot begrudge another saint his sanctity without losing his own.

What we need, Scheler would say, is true Christian charity, which he distinguishes sharply from the self-serving bourgeois sentimentality that goes by that name, and that Nietzsche mistook for the real article. That is because Nietzsche did not take account of the very nature of God as Christ reveals him, the God who is himself love, who pours himself forth from the infinitude of his being, not inevitably and impersonally, as did the “One” of the Neoplatonists, but as a free gift.

Those who seek to be godlike, then, will wish to teach the ignorant, tend the sick, and correct the sinner not from empathy but from “the invincible fullness of [their] own life and existence,” aware that they are “rich enough to share [their] being and possessions. Love, sacrifice, help, the descent to the small and the weak, here spring from a spontaneous overflow of force, accompanied by bliss and deep inner calm.”

We see that bliss and calm in Jesus, who when He urges us to regard the lilies of the field does not say that we should be insensible to earthly things, or grimly stoical. His is a “gay, light, bold, knightly indifference to external circumstances, drawn from the depth of life itself!” Such “inner security and vital plenitude” can love the weak aright, and it grows by such love; it is the very kingdom of God among us on earth. “The deeper and more central it is,” adds Scheler, “the more man can and may be almost playfully ‘indifferent’ to his ‘fate’ in the peripheral zones of his existence.”

The great earthly aim of the Christian faith is not that there should be more of these or those material goods in the world, or an equal distribution of those goods—not only wealth or objects of sensuous enjoyment, but fame, honor, rank, and political power—but that there should be more love that rejoices in the excellence and the beauty of the other.

Out of the fullness of our being we make what Josef Pieper called the fundamental affirmation: How good it is that you exist! Yet we must flush out the impostors, the confidence men of love. One of them, says Scheler, is “altruism.” Altruistic love does not affirm any “positive value.” It is rather a disguised “counter-impulse (hatred, envy, revenge, etc.)” against those who do possess such positive values (courage, generosity, saintliness, etc.). Altruism poses as the universal love of mankind, which results in “the urge to turn away from oneself and to lose oneself in other people’s business.”

The riots today are not prompted by the discovery of saintliness and beauty in the life of George Floyd. Saintliness does not inspire mayhem. People who love beauty do not burn down churches. Floyd himself will soon be forgotten entirely, except as an empty name, a placeholder, an instrument for altruistic ressentiment to lay hold of. Scheler saw the urge to altruism as a form of self-hatred: “We all know a certain type of man frequently found among socialists, suffragettes, and all people with an ever-ready ‘social conscience’—the kind of person whose social activity is clearly prompted by his inability to keep his attention focused…on his own tasks and problems.” He hates his feeling of inferiority, of failure, and so he attaches himself in repressed envy to those who are small and weak, not because he loves them, but because they are the opposite of what he hates:

When we hear that falsely pious, unctuous tone (it is the tone of a certain ‘socially-minded’ type of priest), sermonizing that love for the ‘small’ is our first duty, love for the ‘humble’ in spirit, since God gives ‘grace’ to them, then it is often only hatred posing as Christian love.

If I love you and you are wrong, I will tell you what you must hear, though I may tailor it to your ability to hear it. I will not necessarily feel what you feel, and it is wrong for you to require that I do. For feelings themselves may be evil, though they present themselves as angels of light. But if you say to me, “You must on no account say anything that will trouble me, because I am a victim,” you are like a sick creature snapping at the hand of the doctor, reveling in your sickness and calling it health.

The feminist does not rejoice to see a gang of boys happily and noisily playing football in a field. The critic does not rejoice to see a new artistic genius springing up among us, unless he can use him as a stalking-horse to condemn what he hates. The rioters do not seek friendship between men of different races. By comparison with the salt of a hatred that goes by the name of justice, friendship has no relish.

To anyone with a healthy mind, the rioting is incomprehensible, unless we understand that “inversion of values” that Scheler explains so well. Those who engage in the present destructive frenzy cry out that they have no choice because justice has been denied them too long. The proximate cause is the death of a black man, George Floyd, suffocated under the knee of a white policeman in Minneapolis. When will it matter to the nation, they cry, that black men are murdered by white men, by “systemic racism” and “white privilege” and “four hundred years of oppression”?

One might reply that murder does matter, and that is why we have laws against it, and jury trials, and prison. One might add a rejoinder to the effect that black men murder other black men in yearly numbers that we would not accept as American fatalities in one of our many Middle Eastern wars: more than 5,000 such homicides last year.

White murderers come nowhere near that mark, much less policemen of all races, who last year were responsible, in a nation of 330 million people, for the deaths of a mere 30 unarmed persons—and “unarmed” does not mean “not dangerous.” An accomplice to an armed felon may be unarmed; so might a man strangling someone.

For the rioters, black lives do not matter, just as for feminists, the health and happiness of women do not matter. If the health of women were really the aim of feminists, they would be urging women to marry and to stay married, since a married and never-divorced woman living with her husband is the least likely person in America to be the victim of a felony crime.

I have heard feminists cry out about “women’s health” all my life, as if men did not also get sick and did not die at younger ages than women do. But the same feminists have buried the pathological evidence linking breast cancer and abortion, which unnaturally disrupts a pregnancy just when the woman’s breast cells are in the midst of transformation. Many a male athlete accepts as a matter of course that the artificial testosterone he takes to grow muscle tissue can be carcinogenic; but feminists have not wanted women to hear that the artificial estrogen they take to work the body up into a false pregnancy might also be carcinogenic. Nor shall we get into the matter of placing women—usually of the working class—in front of an enemy’s cannons, grenades, rifles, and bayonets, for no conceivable military advantage.

But perhaps the cause of the present rancor will disappear, when equality, like sediment, settles upon all men in even layers from the east to the west? No, that will not be. It cannot be. The crust of conformity will crack. Mountains will rise. There will always be differences in talent, intelligence, industry, luck, thrift, and so forth. Indeed, as Scheler rightly notes, egalitarianism itself is a source of rancor, because it makes the results of such differences all the more painful for the weak to endure.

Egalitarianism is a rage to reduce. Its power is proportionate to the narrowness of its concentration, a single-minded refusal to recognize the value of the greatness it cannot attain. The ideological egalitarian must reduce man to a thing about which he can make quantitative predications; and then he fights against reality to make the predications come out even, and comfortably low. But man is not a thing. We will recall it someday. A strange time it is when the incendiary throng torch police stations and courthouses, while lonely prophets, like monoliths in a desert, call man back to a real life of communion and love.

Image Credit:

above: detail of the front face of the Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment, a bronze relief sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, located at the edge of the Boston Common (Wikimedia Commons)

Leave a Reply